For many decades in the 16th century, Ponda was a safe haven for Hindus who were fleeing the persecution of the Portuguese inquisition in Goa. Today, the area is not only home to more than half a dozen prominent temples, all located within a close distance of each other, but also the Sanatan Sanstha, an extremist Hindu outfit that has been linked with a number of high profile assassinations and a smattering of bomb blasts. Home to one of the fastest growing cities in the state, the district of Ponda is also the saffron heartland of Goa.

As I walk into the Ramnathi Temple, a few hundred metres down the road from the Sanstha's headquarters in the sleepy little hamlet of Ramnathi, I am approached by a man wearing a bright yellow kurta and a large tilak on his forehead.

"Media?" he asks, half-frowning, half-smiling.

"Yes," I reply, informing him that I am with BuzzFeed.

Several more people appear around us and brows furrow as they attempt to figure out who or what a BuzzFeed is.

Eventually, they introduce themselves as the media liaison team and collectively lead me through the corridors of the temple's rather large and spacious accommodation and administration building. The feeling of being herded is unshakeable.

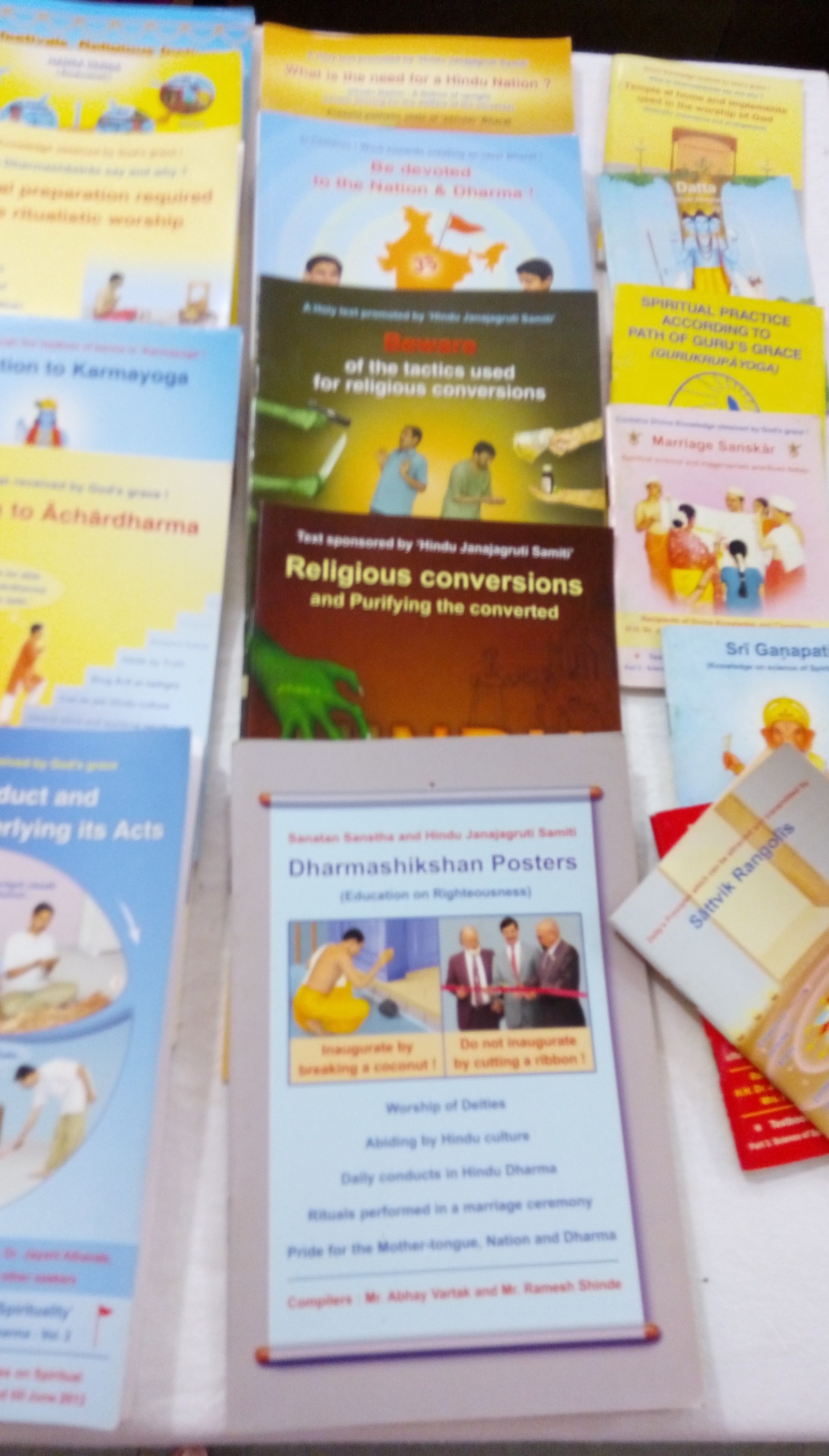

I am here to attend the Akhil Bharat Hindu Adiveshan, a conference hosted by the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti, with the stated aim of charting a path towards turning India into a Hindu nation by 2023.

The Sanatan Sanstha has a number of proxies under which it conducts its various activities and the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti is one of the more evocative of the many names it answers to. For all practical purposes, the two are interchangeable.

Inside the main conference hall, there are attendees wearing kurtas in every shade of saffron imaginable. The walls are decorated with posters extolling Hindu pride and denouncing the various perceived enemies of the faith: Muslims, Christians, Bangladeshis, and Hindus who have strayed from the righteous path. My throat clenches as I realise that last group includes me.

A baby-faced man with an earnest voice is introducing the panel of delegates. He concludes a part of the introductions and suddenly, his voice becomes angry and muscular — and his face contorts into an expression that belies his features.

"Jayatu Jayatu!" he growls.

"Hindu rashtram!" the crowd roar back at him.

This is the cue for Charudutt Pingale, national guide of the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti to take the stage. His primary aim appears to be introducing the organisation and the event, and recounting its achievements, but it’s clear he takes far more pleasure from frequent departures into fiery rhetoric.

He attacks democracy, secularism, minority rights and even the BJP administration, laying out the basic tenets of the Hindu rashtra.

"The division will be on the basis of dharm and adharm. And for those of you who like to call yourself secular, you must take a side or else…" I can't make out the end of the sentence but given the rhetoric that preceded it, it couldn’t have been pleasant.

Pingale ended his speech with a touching thought: "A family which loves each other and takes care of each other is what we need to create in this country," neglecting to mention what place Muslims and other minorities in India will have in this family.

The Hindu rashtra chants ring out again, accompanied by others extolling the greatness of ancient Hindu religion, Shivaji, and several other icons of the Hindu right.

It is hard to tell whether the Samiti will succeed in pulling off its intended revolution, but one thing is quickly becoming clear: they certainly know how to organise and televise a spectacle. Projectors hooked up to giant screens ensure that even the last row in the hall can make out the minutest twitch on the speakers’ faces. A camera unit is hard at work, streaming the event live over Facebook to tens of thousands of followers.

Pinagle's example is emulated and quickly bettered by Ramesh Shinde, the Samiti's national spokesperson, Chetanananda Saraswati, president of Hindu Swabihman, and Abhay Vartak, another senior Samiti member. Saraswati in particular is a fiery orator who struggles to keep the rage in her voice in check, even while making innocuous, polite remarks.

There aren't too many of those in her speech though.

Her basic message is one urging a violent, forceful effort toward the dream of a Hindu rashtra. As she concludes, chants ring out again, this time proclaiming the glory of Hindu heroines like the Rani of Jhansi and Rajmata Jijabai. There appears to be no dearth of variety among the defenders of the faith.

The fringe is forever pushing the BJP further to the right because it is never satisfied and it never shuts up.

Of the three, Vartak’s words offer the most insight into the Samiti's position in the grand chessboard of Indian politics. He criticises the Modi government directly and repeatedly, listing out its failures one by one.

"How can the government say beef is our food in Goa and the Northeast?" he asks, prompting a rousing round of applause. "Have they forgotten that it was the same cow that took them all the way to power?"

Vartak goes on to criticise the administration's inefficiency in dealing with naxalism, corruption, the unrest in Kashmir, and illegal immigration from Bangladesh. The Samiti might be on the fringe of mainstream politics, but the fringe element in the Hindu right is unique in its unparalleled ability to amplify the messages of – and more importantly, offer feedback to – its political leaders. And if Vartak's speech is indicative of anything, it is that the fringe is forever pushing the BJP further to the right because it is never satisfied and it never shuts up.

As the day wears on and the scheduled break for lunch approaches, the crowd grows less enthusiastic. The chanting loses some of its sting. Up steps Sadhvi Saraswati to change all that.

All of 21 years old, the sadhvi is a preacher from Madhya Pradesh with an impressive command over the scriptures and a penchant for slipping Sanskrit quotations into her speeches. But it is her unparalleled ability to spew vitriol about all things adharm that earned her a charge for hate speech at the age of 18, made her a must-have delegate at Hindu gatherings across the world, and propelled her to this particular dias.

She starts off at a gentle canter, quoting from the holy books to illustrate the importance of the ancient Hindu culture, but quickly switches gears and charges headlong into hyperbole about “the dirty Muslims who are polluting India.”

"The time for talking is gone. It's time to pick up weapons and fight!" she thunders at the audience, urging Hindus to arm themselves for the coming war.

As the topic of discussion turns towards the cow, it becomes apparent that her true passion is of the bovine persuasion. With conviction that could make corpses stir, she describes her attachment to the cow, her mother. She viciously condemns anyone who would dare hurt her mother.

Pens start to scribble furiously in the press gallery as reporters sense headline material. The sadhvi does not disappoint.

"Anyone who eats beef should be hung publicly to make an example of them," she bellows.

As enthusiastic war cries fill the air, I realize that I could use a smoke.

A shopkeeper outside the temple tells me by far the strangest story about the Sanstha that I will hear all week. Nearly a decade ago, a septic tank in the Sanstha's ashram burst, raining hundreds of used condoms down on the rice fields that surrounded it. The organisation claimed that the condoms were used by married couples living in the ashram.

The shopkeeper – and several other locals – proffer a different theory. One that involves depraved orgies organised by a sex cult that uses religion as a facade.

It is hard to separate the truth from the general hostility and distrust that the Sanstha evokes amongst its neighbours. But either through a condom-infested sewage explosion or neglect, the once-fertile fields around the ashram are now abandoned, overgrown with weeds.

Back inside the temple complex, a press conference is underway. Predictably, the sadhvi is the star of the show.

"Will you take responsibility for any violence or riots your statements may cause?" asks one reporter.

"If it is being done for the dharm, yes."

Pressed to clarify what she thought of the constitution and the rights guaranteed by it, she replies, "I believe in dharm first and then the constitution."

"I believe in dharm first and then the constitution."

I ask Ramesh Shinde, the only official representative of the Samiti at the press conference, if his organisation endorses violence. He takes several minutes to provide a non-answer that takes no discernable stance.

"We aren't hatching any conspiracies here," he says. "We feel that the only real solution to all the issues plaguing India right now is the creation of a Hindu Rashtra."

A gaggle of TV reporters are now queuing up to get one-on-ones with the sadhvi, hoping they can tempt her into making her already vicious statements even more provocative. She obliges happily.

I pull Shinde aside and ask him to clarify his earlier answer. What exactly is this Hindu rashtra and how is it going to solve problems like corruption and terrorism and inflation?

"Look, India was a great country in the past. This is well documented. Once upon a time, we controlled a majority of world trade. Look at us today, we are topping the corruption index. Modi is trying, but he can't really change everyone's mindsets. That is the larger battle. People's mindsets have to change. And dharm does this. It teaches you how to be a good person. And when everyone's intentions are good, the nation will definitely be great again."

Three hours later, the sadhvi is back on stage and in her element again. The session is about the cow and she appears to have gotten angrier about its treatment over lunch. She is now calling for the limbs of beefeaters to be hacked off before they are hung. I am preparing to beat an early exit. But in the time that it takes for me to make my way from my seat to the door, the tone of the discourse changes completely.

The new speaker is Virendra Ichalkaranjikar, an advocate from Maharashtra and a senior Samiti member — and he is talking about the environmental impact of eating beef. "It takes 15,000 litres of water to produce 1 kg of beef. Not to mention 7 kg of grain. So in effect, we are taking food and water out of one person's mouth in order to feed someone else beef." Unlike the sadhvi, he makes no mention of ancient Hindu culture or butchering infidels.

All the cow-talk had made me crave a good steak, and Ichalkaranjikar is now making me feel rather guilty about it.

Although there were sessions scheduled from morning till night spanning four days, the media has only been allowed access to a handful. Any attempts to enter the premises outside of the permitted windows draws the immediate attention of the media relations team.

In fact, by day two of the conference, I discover that even the simple act of talking to an attendee, particularly those from abroad, will instantly conjure a disapproving volunteer informing me that I need to take permission before conducting interviews. The Sanstha is clearly quite particular about controlling the message, but inexplicably, they are only comfortable with publicly discussing their most controversial stances, preferring to conduct the more seemingly innocuous sessions behind closed doors.

This irony is perfectly exemplified by the first session of the second day, which features delegates from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka discussing the persecution of Hindus in their countries.

"The Buddhists have the support of the government, the Muslims have the Arabs behind them and the Christians are backed by the West. Where do we go for support? Do you want to abandon us?" asks Maravanpulavu Satchidanandan, the Sri Lankan delegate, making an impassioned plea for support from his Hindu brethren in India.

The audience takes up a brand new chant. "Ram naam sab gayenge, hum sub Lanka jayenge," it tells him, in one voice. He seems placated.

Rabindra Ghosh, founder of Bangladesh Minority Watch, makes a similar appeal as he describes what he calls "state-sponsored ethnic cleansing" in his country. "We liberated the country, not just for the Muslims, but for everyone. Islam was not part of the original constitution of Bangladesh but the secular ideal has been lost over the years," he laments.

The inherent contradiction of advocating minority rights from a stage that was used just a day ago to denounce secularism and attack minorities, seems to bother nobody at all. The poster denouncing illegal Bangladeshi immigrants has mysteriously disappeared.

I catch up with Ghosh after the session to try and address this paradox.

"I am a secular man," declares the former freedom fighter who appears to be a man weighed down by the scars of the many battles he has fought over the course of his life. "Yes, the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti wants a Hindu Rashtra. But in Bangladesh, how can we demand such a thing? We merely want equality, to live without fear of persecution. Equality, not just for the Hindus, but for all the minorities of Bangladesh."

Pushed further, he admits that the aims of the Samiti and his organisation are "quite contradictory."

It becomes easier to understand his presence in Ponda when you realise that Bangladesh Minority Watch is an organisation funded entirely out of Ghosh's income as a lawyer. It has no friends in high places or networks of donors. The BJP and the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti are the only potential allies to have stepped forward and offered to aid his lonely quest.

Having been abused, threatened, and even physically attacked by opponents of his work, it appears that Ghosh considers muzzling his ideology a small price to pay if it means he can protect a few more lives.

As the conference wears on, the media schedule starts to shrink as session after session gets cancelled or redesignated as a closed door event. There are rumours that the organisers aren't happy with the negative coverage they’ve been receiving. Reporters whisper amongst themselves about who is more to blame. Everyone is keen to claim their rightful share.

The final press conference is being held in Panjim, and a whole new contingent of reporters have arrived to replace the ones who had slowly dropped out one by one back in Ponda. Ramesh Shinde introduces the panel of speakers, which includes two full-fledged members of the BJP — an MLA from Telangana and a Media Cell member from Odisha.

"The BJP is a party that allows dissent. When we sit in our annual meetings we will probably take pointers from this conference."

Shinde then announces the various resolutions adopted at the conference: a demand for a nationwide ban on cattle slaughter, a plan to march to Ayodhya if the Ram Mandir project is not initiated soon, and of course, an agreement amongst various attending organisations to work towards the dream of a Hindu Rashtra. The MLA, Rajasingh Thakur, even announces that he will resign his post if construction of the Mandir hasn’t begun by 2019.

I ask the one question that’s been burning a hole in my head all week: What is the Hindu Janajagruti Samiti's relationship with the BJP and why do members of the party feel the need to use this platform to criticise their own government? Clearly needled, Anil Dhir, the BJP spokesperson from Odisha responds, "The BJP is a party that allows dissent. When we sit in our annual meetings we will probably take pointers from this conference."

Later that day, I travel across Goa to meet some friends. I am determined to put thoughts of the last few days out of my mind and just be susegad for a night. We head to a bar on a narrow back road that would be impossible to find unless you knew exactly where to look. A new band is playing and a crowd has gathered, most of it spilling over onto the road.

It seems like a carefully staged scene crafted of the best Goan stereotypes: young backpackers from around the country and the world, middle-aged hippies with their children, and an assortment of Goan families all revel in the music together, moving to the music, beers in hand and lit cigarettes in their mouths.

A herd of cows wanders into the midst, and the crowd clears to let them pass.