“It’s called fishin’, not catchin’!” our first mate called out from the other side of the boat as I reeled in my once-again-empty line. Wendell was repeating an exchange he'd had with a kayak fisherman we'd passed in Rudee Inlet minutes before. Our first lesson in fishing from First Landing Charters was this apparently routine social ritual among fishermen:

Wendell, calling out and waving, catches the fisherman’s attention and thrusts his thumb out, alternately flipping it up then down, up then down.

The fisherman shrugs and motions with a shimmy of his flat outstretched palm: so-so.

Wendell, in consolation: “It’s called fishin’, not catchin’!”

Fisherman, with a smile: “Beats workin’!”

I completed the bit as the kayaker had — and with enthusiasm. Except, technically, I was working, spending a few days on assignment around the longest beach in the US at the invitation of Visit Virginia Beach. But as far as working goes, I had definitely had worse days — and on land, no less.

Once again, I flicked the rod toward the dock where our captain, Jay, indicated there would likely be fish. I liked casting, I learned. Tossing the hook out into the water and reeling it back in, attempting to lure some ill-fated puppy drum (the affectionate moniker for a juvenile red drum) with the flickering fake tail of neon-green bait... I much preferred it to drop fishing, which felt too much like sitting around.

Suddenly I had a bite.

“Reel! Reel! Reel!” Captain Jay cheered. My suddenly slippery hands, a sign to me that I was actually enjoying fishing, attempted to comply, but in an instant it was over. No croaker, no flounder, no puppy or full-grown drum. Just a bit of artificial bait and disappointment still dressing the hook. This was fishing, Wendell explained: “90% waiting around for 10% excitement.” I could see why so many people get hooked on the process; the 90% was simply lounging about on a boat, and that placidity perfectly contrasted the intensity of the other 10%.

I deflated at the end of the morning, empty-handed and empty-hooked. I had my own expectations to blame, apparently. “People who just want to spend a nice day out on the water always catch the biggest fish,” Jay assured me. “It’s also the water. Just five degrees warmer and I guarantee you would’ve caught one.”

Located at the intersection of the Atlantic Ocean, the Chesapeake Bay, and numerous waterways, Virginia Beach thrives on water. Water is nearly half of the city’s total area of approximately 500 square miles. The population of Virginia Beach hovers around 450,000, but according to locals, the number of people more than doubles in the summertime, with sun-seeking visitors swelling up along the shoreline, particularly the three-mile-long oceanfront boardwalk.

This 59-block-long stretch is lined with hotels, restaurants, statues, and even a small amusement park. It also hosts various festivals in the warmer months and joggers, bikers, and Rollerbladers at any time of year. But though Virginia Beach is ostensibly a resort city, it’s largely suburban outside of this stretch and feels less like a city than it does a kind of nice neighborhood — narrow streets, perfectly preened drives, cedar shake siding — with a particularly popular stretch of sand connected to it.

This stretch is, however, worthy of its notoriety. Virginia Beach’s coastline comprises 35 miles of beach: Virginia Beach, Chesapeake Bay Beach, and Sandbridge Beach, together forming one of the world’s longest beaches and, yes, the longest beach in the United States.

Instead of going on foot, we decided to explore the beach on horseback. I was paired with a palomino named Tracker at Virginia Beach Horseback. “He’s got a real smooth trot,” the guide told me while she helped me up, and she was right. After saddling up, we headed south toward the pier at an easy pace with a bit of trotting. It's not a strict nose-to-tail trail ride, so we were given a bit of freedom to go at our own pace and enjoy the views of the hotel-lined boardwalk on one side and the crashing waves lapping at our horses’ hooves on the other.

Had we continued riding north on our return journey, we would have reached Cape Henry and First Landing State Park, where we later kayaked with Chesapean Outdoors. The most unique thing about Virginia's most popular state park is its variety of flora. Virginia Beach is home to many species of subtropical and tropical plants that don't venture any farther north, and as we kayaked through the brackish waters, our guide, a local named Eli, drew our attention to live oaks dressed in Spanish moss. In fact, First Landing is actually the northernmost point of the natural environment for Spanish moss, which won't reliably grow any farther north.

On that sunny day, as a few bald eagles and even a skein of pelicans passed overhead, Eli demonstrated his arboreal prowess, drawing our attention to the ironwood, loblolly pines, and cherry blossoms flanking the banks of Wolfsnare Creek. He then led us carefully through a grove of chillingly beautiful dead and fallen trees, which he described as "the bad part of The Lion King." "Usually the tide is too low to get in here," he said, squinting through his polarized sunglasses as he pointed out a nesting osprey. "You guys are lucky. I've never even been able to come this far."

Eli spent much of his childhood in this park, hiking and fishing around Chesapeake Bay, which happens to be the largest estuary in the US. Estuaries frequently act as nurseries for young fish and crabs and are critical for the ecological health of an area. This estuary recently made quite a comeback. With the return of eelgrass, which is important for nesting crabs, other species have also made a turn for the better; oysters, especially, have been flourishing, in turn improving the conditions of the bay through water filtration.

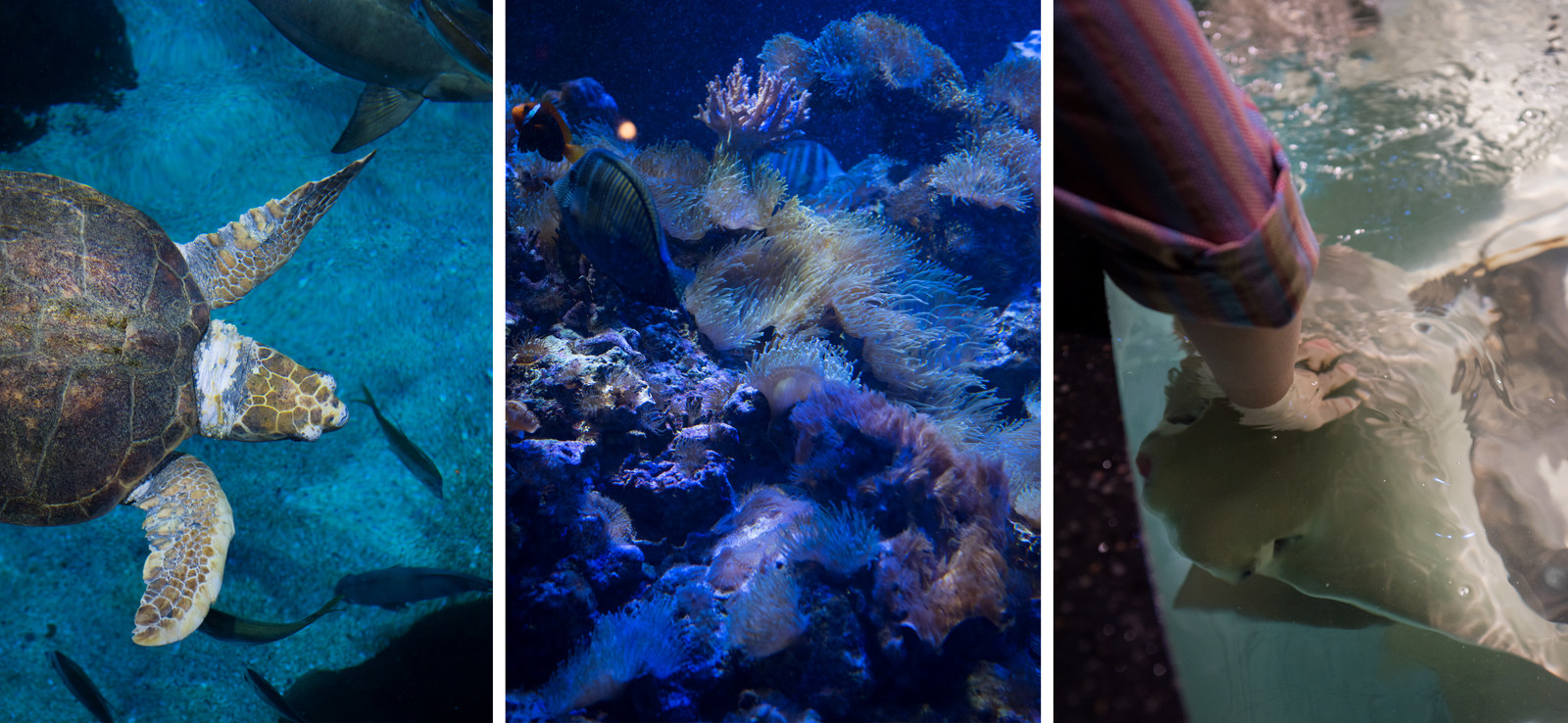

Wanting to delve deeper into the waters of Virginia Beach, we paid a visit to the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center. Our first stop, the Light Tower Aquarium, was fashioned to resemble the environment surrounding the actual Chesapeake Light Tower, a popular locale for divers. Four sea turtles — two loggerheads, a Kemp's ridley, and a green sea turtle — reside here alongside a cobia and a barracuda.

We watched as the massive and strangely majestic 200-pound-plus turtles were fed from a platform surrounding the perimeter of the top of their enclosure. It’s not commonplace to get this close to a sea turtle when you’re living in New York, and I was stunned by their size and surprising elegance as they glided gently through the water, their variegated shells occasionally skimming the water’s surface a few feet away from me.

Each turtle, paired with a trainer lying prone upon the platform, was prompted to tap a colored target with its nose. In return, the turtle was offered a fish with long forceps. The benefits of this feeding process are threefold: It reduces the risk of aggression between turtles, keeps the turtles acclimated to human contact for veterinary visits and other checkups, and individualizes them so as to monitor their food intake for possible adjustments.

All four turtles have been deemed unreleasable for one reason or another. Turtles can be victim to boat strikes and fishing hooks, as well as prolonged exposure to cold-water temperatures, which lead to something called “cold stun.” The aquarium’s Stranding Response Center is open 24 hours a day and 365 days a year to assist and revive injured and ill sea turtles and marine mammals, such as seals, dolphins, and whales. When we visited the facility, which is funded completely by donations and grants, they had four sea turtles in recovery, including three Kemp’s ridleys, the most endangered of all sea turtle species.

Our last stop was actually the first exhibit you see before you even enter the aquarium, one in which you can observe a slippery shadow or two just from the parking lot: the harbor seals. Upon entering their exhibit, Peter immediately slipped out of the water and bounded clumsily and steadily toward us, searching us with his eyes — two impossibly dark, large pools of what seemed to be bottomless curiosity. Hector, the one and only Pacific harbor seal of the group, stayed behind in the water, bobbing up and down with marked effort like a child hopping up and down on tiptoe to steal glances over a just-too-high fence.

“They each have their own funny personalities,” one of the trainers said before she began one of their two daily feedings that demonstrate the seals’ many talents. “They’re not tricks,” she was careful to explain. Just as with the sea turtles, the animals are not forced to perform any behavior but are given the opportunity to.

From simple acts — like spinning in the water, vocalizing, hiding their faces, or swimming — to the exceedingly cute and/or advanced — like blowing bubbles; painting with a brush; or “danger,” which consists of a seal swimming on its side with one fin up to mimic a shark — all the seals' behaviors are either demonstrated in the wild or make it easier and safer for vet visits and other regular grooming activities like nail trimmings. I didn’t ask for the practical reason behind giving kisses; I was simply grateful when I received one from Peter. And, no, I didn't care that he was ultimately doing it for food.

Of course, it's impossible to talk about Virginia Beach's coastline without delving into seafood. After all, the name "Chesapeake" is believed to mean “Great Shellfish Bay” in Algonquin due to its abundant underwater cornucopia of crabs, oysters, clams, and mussels. Most restaurants featured Virginia Beach's famed seafood, but Chick's Oyster Bar, an old standby overlooking Lynnhaven Inlet, was recommended by nearly everyone we spoke to, thereby making the top of our list.

Our order: a variety of crushes (boozy, fruity drinks in crushed ice popular in the area), Chick's Steamed Combo (oysters, clams, shrimp, and mussels, perfectly seasoned and more than enough for two), steamed crab legs (served with the requisite drawn butter, of course), and Oysters Rockefeller (local bivalves baked with a savory mix of spinach, bacon, and Parmesan on top). We polished it all off, leaving only empty shells and crumpled towelettes smeared with Old Bay in our wake.

Not ones to slack when it comes to eating, we also paid a visit to The Back Deck, a casual spot hidden behind a seafood market, for beers, raw oysters, and a truly unforgettable crab dip. On top of that, we each savored a slice of delectable, crumbly, perfectly mouth-puckeringly zesty key lime pie. Call it indulgent, but I prefer the word "ambitious." ("Hungry" also works.)

In the end, I didn't have to catch any fish to get my fill of seafood. (Captain Jay assured me there was no shame in it.) But I did leave Virginia Beach hungry — hungry to go fishing again. I was also hungry to return to Virginia Beach to spend more time in and on the water, parasailing, stand-up paddleboarding, and even searching for dolphins that often visit Chesapeake Bay. Maybe next time I'll actually earn my meal, though perhaps I'll try my hand at oyster harvesting; I've heard there's an almost 100% success rate with that.

Photographs by Sarah Stone/© BuzzFeed

It's too easy to spend more time on the water than on land when you're in Virginia Beach. Don't miss out on all the boating, fishing, and water sports this summer. Plan your trip to Virginia Beach now.