It’s time I came clean.

On the night of the 4th of July, a few friends and I wandered down the empty beach of Fire Island Pines, an infamous barrier island off Long Island, masks on and chests exposed, looking for something fun to do. Ideally, “something fun” meant music and people spread out enough to talk and flirt with who we wanted to, but also keep a reasonable distance from whomever else. What we were looking for never materialized, but we’d heard of another function in the dunes that separate the Pines and Cherry Grove (the Meat Rack). It sounded like trouble, but we were already halfway there and decided to at least check it out.

As the crowd came into view, I felt the strange dissonance between warm familiarity and abject horror, between the thrill of nightlife as I remember it and the recognition that nightlife is now bound up with potentially deadly repercussions. I dragged myself through a sardine tin of sweaty, ecstatic bodies, people who had taken off their masks to kiss a boy and never put them back on. I hoped that a more dispersed scene might be on the other side. There wasn’t, rather just a membrane to the crowd where zombified partiers stumbled outward to vomit into bushes and try not to lose consciousness.

We’d seen enough, and we fled back to our respective houses. I changed into an oversize cotton shirt, the kind I can pull my whole body inside of, and went to the beach to smoke a joint beside the ocean. A close friend joined me, and we talked tenderly about boys under the full moon. This is one of my favorite things to do on the island, and where I wound up most of the nights I was there.

Sunday through Wednesday are typically quieter and calmer on Fire Island, but this time they were especially reflective for me. Damning footage of the weekend’s pandemic-defiant festivities had gone viral, inspiring well-rehearsed takes against the decadent Fire Island Gays that appeared compulsory if you were gay and online. Needless to say, I felt terribly implicated as I sipped an Aperol spritz beside a heated pool. On the island, I had much calmer offline conversations about what had happened and what to do moving forward to mitigate risk.

What actually did happen? Social life involves a thousand caveats whereby a hangout slips into a party, or a spacious outdoor gathering slips into a steamy crowd. The novelty of a restructured environment made it hard to imagine what potential pandemic caveats might be, and what boundaries we would need to set in advance. We wanted very badly to be with other gay people and to do gay things in a gay place. Nobody had sorted out the details of what safety could look like right now without dismissing those wants altogether. So people improvised.

My friends and I advised each other to quarantine and get tested afterward. I kept in touch with housemates and friends to make sure nobody was experiencing any symptoms or tested positive. I didn’t catch COVID, nor did anyone with whom I’d been spending time.

Over the month since the holiday weekend, we did not see a substantial surge in cases in New York. And the changes we did see were compounded by not only plenty of other socially proximal gatherings that weekend, but also by the government rush to reopen businesses, placing low-income residents who cannot work from home on busier subways and buses to serve higher volumes of clientele.

This absence of a local case surge was somewhat irrelevant to the criticism leveled against the partygoers, which is that they presumably did not care about the effects in the first place. Photos and videos circulating around social media depicted Fire Island as a mess of drug-addled disregard for social distancing, in spite of successful efforts to normalize mask-wearing along the boardwalk and restructure food and grocery establishments outdoors. This footage so thoroughly echoed images of pandemic denialists in conservative communities that onlookers seemed to view them as one and the same.

But here’s the thing: They’re not.

Distinctions between various spectacles of seemingly sporadic irresponsibility are worth making, because the ways all of us negotiate risk, trust, and desire are varying more and more widely each day. This includes essential workers, who are not just heroic props in our culture war over contagion, but real people who seek their own share of leisure and social life when they’re not working. In spite of these lived complexities, pandemic ethics tend to reduce everyone into a binary of good, vigilant quarantiners versus selfish, stupid bioterrorists. Though the line between these positions has shifted within short spans of time, yet the parameters of good behavior are always considered self-evident.

Often, these ethics aren’t even buttressed by science but by the “hygiene theater” of a society desperate to justify risky reopenings. Risk and responsibility are flattened into moral absolutes, in spite of clear geographic differences in the virus’s prevalence, governmental responses, and social norms.

"We have not been encouraged to manage risk through harm reduction...but rather to see safety and danger as a matter of all-or-nothing ethical constraints."

In Fire Island, where events and parties are otherwise organized very clearly, norms around ethically socializing hadn’t been firmly established until very recently, given that it was once hardly permissible to socialize at all. For some, it’s still not. Navigating Fire Island on its first high-volume holiday weekend of the summer involved navigating unfamiliar circumstances of risk and desire that can escalate quickly and confusingly, necessitating boundaries that we only learn to assert through practice and compassionate advice.

The tricky thing about boundaries, after all, is that we rarely know what they are until they have been breached. Individual slippages in social distancing often take place in a gradual drift from low risk to something more, and many times we do not notice our ethical discomfort until we’re already past the point of no return. Despite our convictions, we find caveats, exceptions, and gray areas all the time — not only during a pandemic, but when we’re navigating the hundreds of moral questions, big and small, that can crop up for us on any given day. We have not been encouraged to manage risk through harm reduction — a variety of tactics for blunting our desires into less harmful behaviors — but to rather see safety and danger as a matter of all-or-nothing ethical constraints.

It is in part this widespread assumption that you can be either careful or careless that drives people to binge on respiratory droplets for a weekend after months of avoiding human contact, rather than maintain a flexible sense of caution.

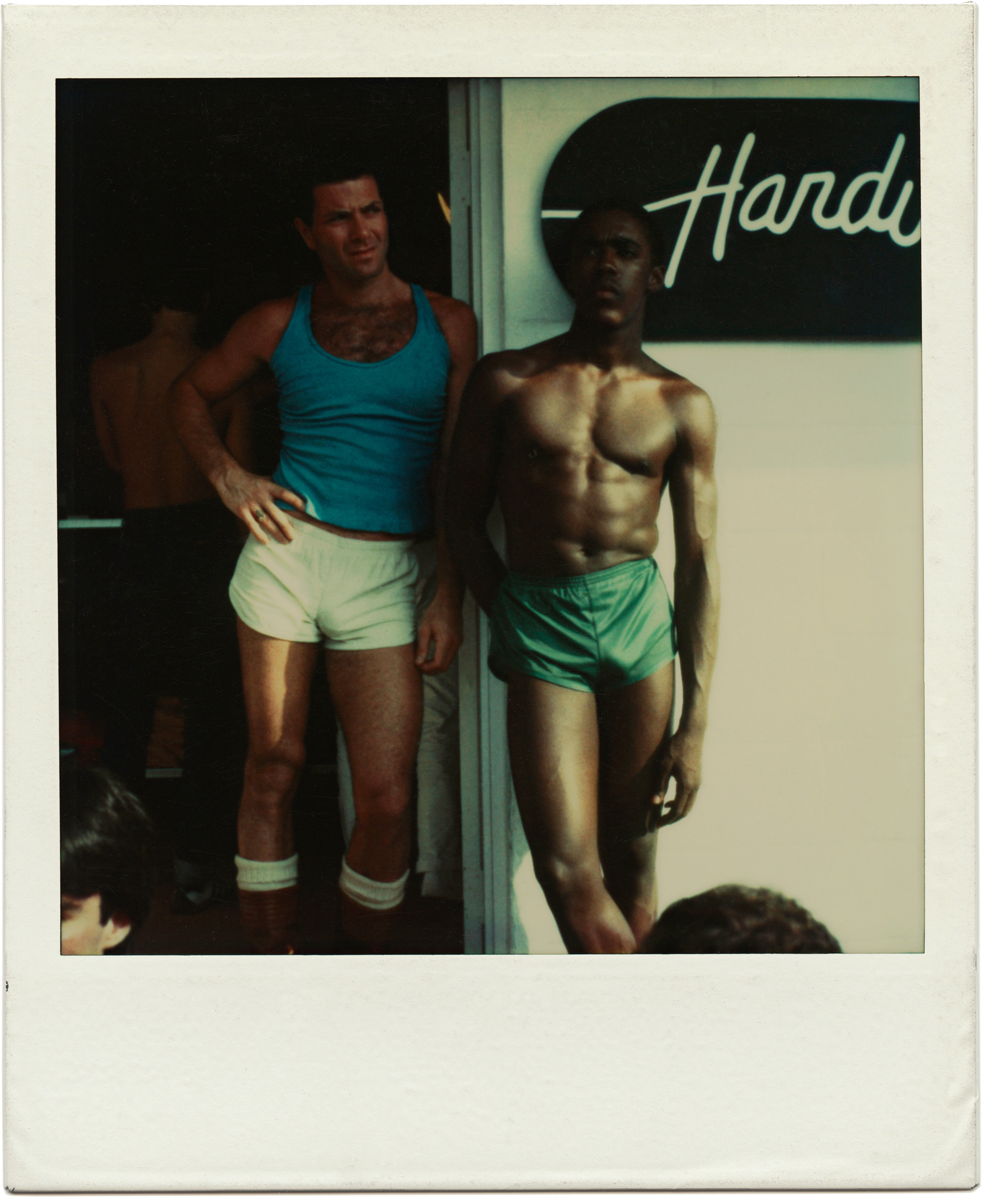

Fire Island’s reputation of homosexual excess makes it especially prone to absolutes, such that most visitors never learn to see past its glamorous mythos of parties and sex.

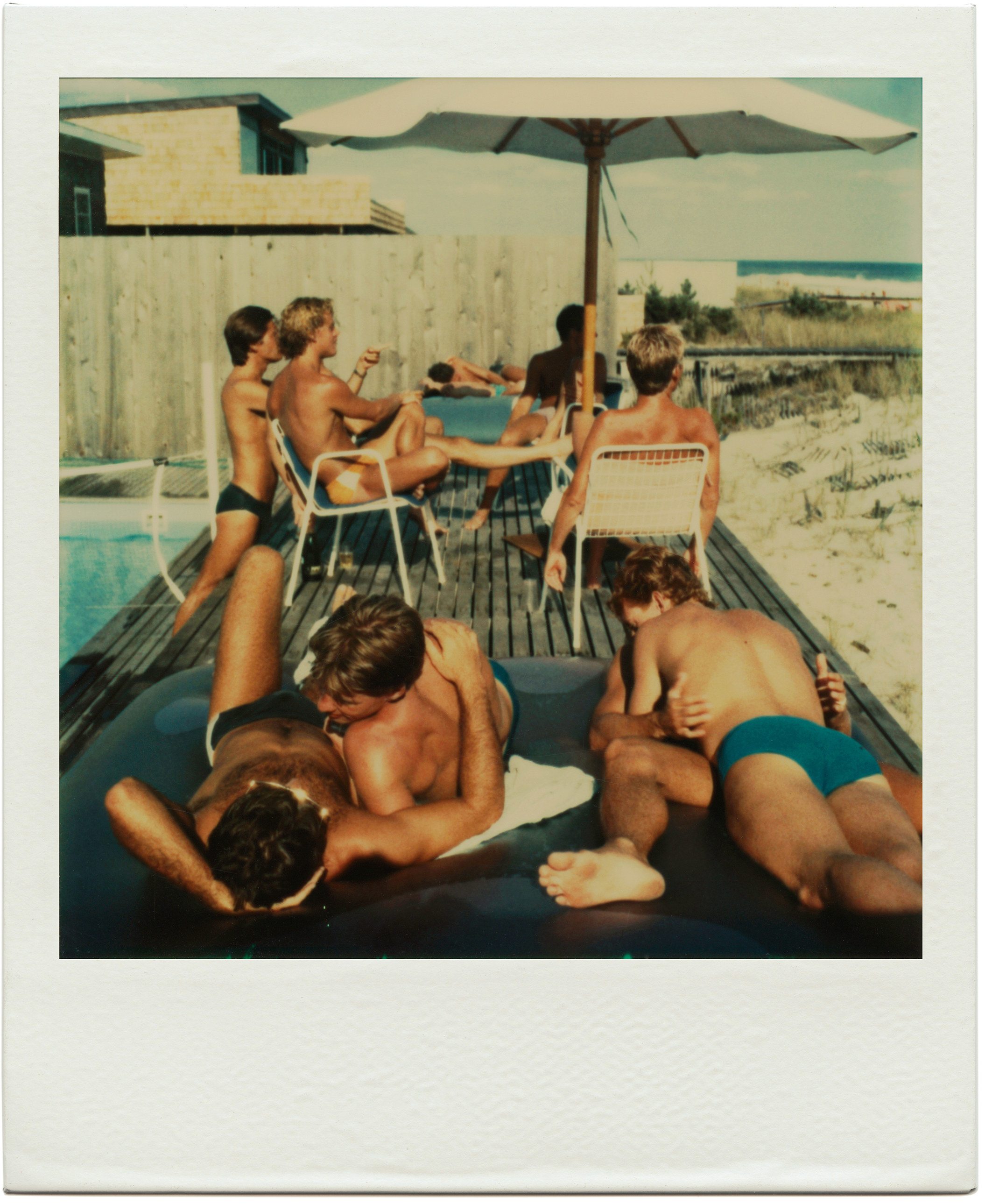

Critics and enthusiasts alike share a widespread misconception that Fire Island is only a compulsory program of parties and orgies, like a sleepaway camp sponsored by some MDMA kingpin. Relatively few appreciate how Fire Island is naturally and architecturally dazzling enough to be more than its parties. The beaches are spacious and clean, and accessible at any hour you need them. There is a Sunken Forest past Cherry Grove that makes for a nice hike, especially if you like psychedelics. Drag abounds, and even the crustiest wig earns the appreciation of passersby on the boardwalk.

And it is a wonderfully haunted place, rife with ghosts of the queer people we have lost to AIDS, drugs, and loneliness, who float invisibly between houses and across dunes, sometimes passing right through you. In fact, I think the parties tend to be the worst part.

I consider myself somebody invested in tracing a gay lineage for myself. I try to do this through gay art, literature, and travel, even when parts of that lineage might also annoy me. I feel a peculiar spiritual pleasure in enacting the same pilgrimage to the Fire Island detailed in Andrew Holleran’s vital gay novel Dancer from the Dance in 1978. Or discovering a photo on the AIDS Memorial Instagram from the summer of 1983 of gay men on the same couch in the same house I stayed at last year. Or relating to playwright Jeremy O. Harris’s refrain in his own “choreopoem’” on gay sex and literary lineage, Black Exhibition: “I came to Fire Island to write, and all I did was fuck and cry.”

In Fire Island I have learned how once you locate the parts of the past to which you belong, history is a rich and pleasant feeling, not just an assemblage of facts. Navigating the Pines in a pandemic only sharpened that feeling, given its role as a vital refuge for gay people at the height of the ongoing AIDS epidemic. It was there that many queer people possessed the space and openness to cultivate networks for education, care, and grief among ourselves to survive HIV/AIDS (or live out our final days of it.) And in this way, it provided a kind of laboratory for crafting modes of pleasure and intimacy within new parameters of risk. Even though COVID-19 differs greatly from HIV, the task of defying disease rings out with a particular, historical vibration in Fire Island.

But, like most gay spaces, Fire Island is also a hotbed of anxiety and ambivalence. Everybody feels it; it’s just that some people conceal or suppress it more immediately than others. The hottest people I know confide to me that they feel insecure in the constant swimsuit pageant of the boardwalk. There is a feudalistic quality to homeownership on the island, leading many to believe in the myth that it is necessary to charm super-affluent older men in order to access the island at all. Rather, many secure lodging by assembling a group to split the costs of a rental several months in advance. Space is still pricey and limited, though, which produces some unnerving dynamics between those who have and those who have not.

There is also the predominance of white men in Fire Island. In addition to structural disparities in the discretionary income that affords a beach vacation, racism abounds in the ways white gays fail to integrate people of color into the kinds of social circles that wind up sharing a rental, as well as the daily microaggressions people of color experience when we do procure an invite or even a house of our own.

At the same time, it is easier and more pleasant to separate oneself from white people on a sandbar than in a gay bar. There are queer people of color in Fire Island, who like beaches and nice houses and casual drag, and we appreciate finding each other even as we resent having to look. Critiques of Fire Island’s whiteness are necessary and accurate, but some of these critiques also erase those who do try hard to stake a claim to the space, and deter more of us from ever attempting to do the same.

Perhaps it is this assumption of an all-white space that made commentators comfortable calling for police intervention to crack down on social gatherings. As photos of packed beaches and pool parties went viral over 4th of July weekend, Fire Island Pines’ scandalized Property Owners Association announced that it had encouraged local police to “be more vigilant” in enforcing social distancing measures. Self-righteous social media pundits called for fining, arresting, and even forcibly quarantining the whole island using local police forces. As a result of these demands for intervention, police drove down the beach for the next few days, bothering any small group of people to wear their masks. They’d been shutting down parties before, but now they were shutting them down a little bit faster.

Meanwhile, Gay Twitter became obsessed with properly disciplining its longtime nemesis, the Fire Island Gay. If harnessing police against these bad boys was untenable, then perhaps we could hold them accountable using the disapproval of strangers — especially strangers within their own LGBTQ community. Perhaps this maelstrom of shame pushed some people to think critically about their actions, but the most common takeaway seemed to be that if you decide to do anything social, you should just avoid letting the Internet find out about it.

"But it’s also not wrong to be enraged."

These criticisms appeared particularly clueless after protesters across the country had just spent over a month passionately objecting to police departments and their role in enforcing white supremacy. The central demand of this social movement was not to tweet out Black Lives Matter hashtags, but that our society must relinquish its reliance on policing and punitive justice by defunding the police and reimagining how we all respond to needs in our communities in a less harmful way.

But it’s also not wrong to be enraged. The holiday partying happened as the state of New York was finally seeing cases trend downward and stay there after months of economic and emotional devastation. And anger is a natural reaction to the pain that the pandemic has created and also revealed.

Over 165,000 people in the United States have died so far and millions more have lost their jobs as a result of COVID-19, which has mostly been a result of our government’s outright refusal to subordinate capitalism’s well-being to the preservation of human life. Structural racism has placed Black and Latinx Americans in more risk-laden jobs and housing; they are three times more likely to test positive for the virus, and twice as likely to die from it. Rather than cancel rent payments or protect workers who are exposed to the virus from loss of income, reopening plans have proceeded across the country in blatant disregard of rising cases in most states. Up against these more systemic obstacles to prevention, condemning people isn’t just simpler than transforming society — it also feels better.

But our choices are not made in a vacuum. It is, in fact, the state’s management of material incentives and structures that facilitate individual behavior, not some innate moral fortitude. We can usually chew gum and walk at the same time, but our fixations on individual behavior tend to just further enable the state to neglect its own responsibility for the pandemic and convert resolvable problems of governance into unresolvable conflicts of culture. Plus, stigmatizing people who engage in risky behavior isn’t even effective. Stigma tends to drive shameful behaviors into secrecy rather than reduce them, and in the context of a pandemic like COVID-19, such secrecy only undermines efforts to keep gatherings out in the physical open and ensure accurate contact tracing. The alternative to shame isn’t permission to behave carelessly, but coming up with more persuasive and sustainable tactics for keeping each other cautious while we pursue what we want.

I cannot be sure precisely how all those boys wound up crammed together in the Meat Rack, but if we take seriously the more rational and material reasons for taking these risks, even when these reasons aren’t very good, then we can actually mitigate the behavior. Many gay people have learned to cope with our anxieties and loneliness by seeking out other gay people. Masks make it near impossible to flirt with an unfamiliar person, and this is often the basis for taking them off.

Addressing risk in places like Fire Island requires us to acknowledge this natural desire to feel sexually seen and experience social variety, especially when the satisfaction of those desires becomes available very suddenly. We can satisfy some of these desires in less harmful ways than drug-fueled orgiastic free-for-alls, but not if we dismiss what is challenging about them to people who have relied upon gay sexual culture to meet our emotional needs.

The threat of backlash has made many of us reluctant to share the compromises we have attempted to make it through this pandemic and the boundaries we have discovered for ourselves. Perhaps we can begin to register the ways in which we are not entirely “in this together,” but possess different desires and come from different contexts for risk.

Perhaps we can come clean about our attempts to not just survive this catastrophe, but to find pleasure during it. And when we find ourselves seeking reprieve in wonderfully haunted places like Fire Island Pines, we can begin to guide each other beyond the parties and sex, not just against them. Because there is always the beach, and there are always the ghosts.