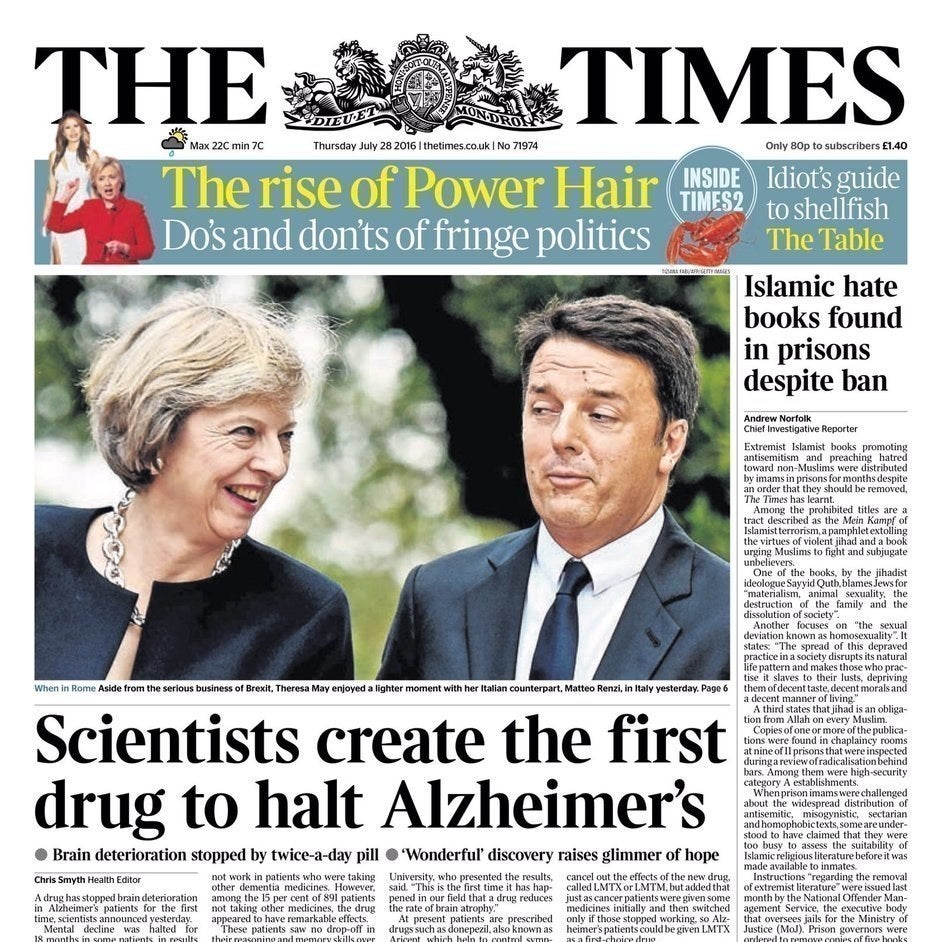

If you've read the news this morning, you might get the impression that we're about to cure Alzheimer's disease.

The Times reported: "A drug has stopped brain deterioration in Alzheimer’s patients for the first time … Mental decline was halted for 18 months in some patients, in results hailed as the strongest sign yet that an effective treatment for the disease is near."

The Sun said something similar, adding that "key areas of subjects’ brains also shrank a third less than others in the trial". The drug in question, known as LMTX and made by a Singapore-owned pharmaceutical company called TauRx Therapeutics, apparently dissolves a protein called "tau" that builds up in the brains of patients with certain forms of dementia, including Alzheimer's.

But in fact, the trial had a negative result. The primary finding was that the drug had no effect.

The TauRx press release says that the trial missed "co-primary endpoints as LMTX as add-on therapy shows no beneficial effects". What that means is that on average, people who took LMTX did no better than people who took a placebo.

So how come it's being reported as a success? It seems to be because, after the study came back negative, the authors started dividing the data up until they found a positive result.

The study looked at 891 people. It found that in one subgroup – the 15% of patients who took LMTX without any other drug – there appeared to be a benefit.

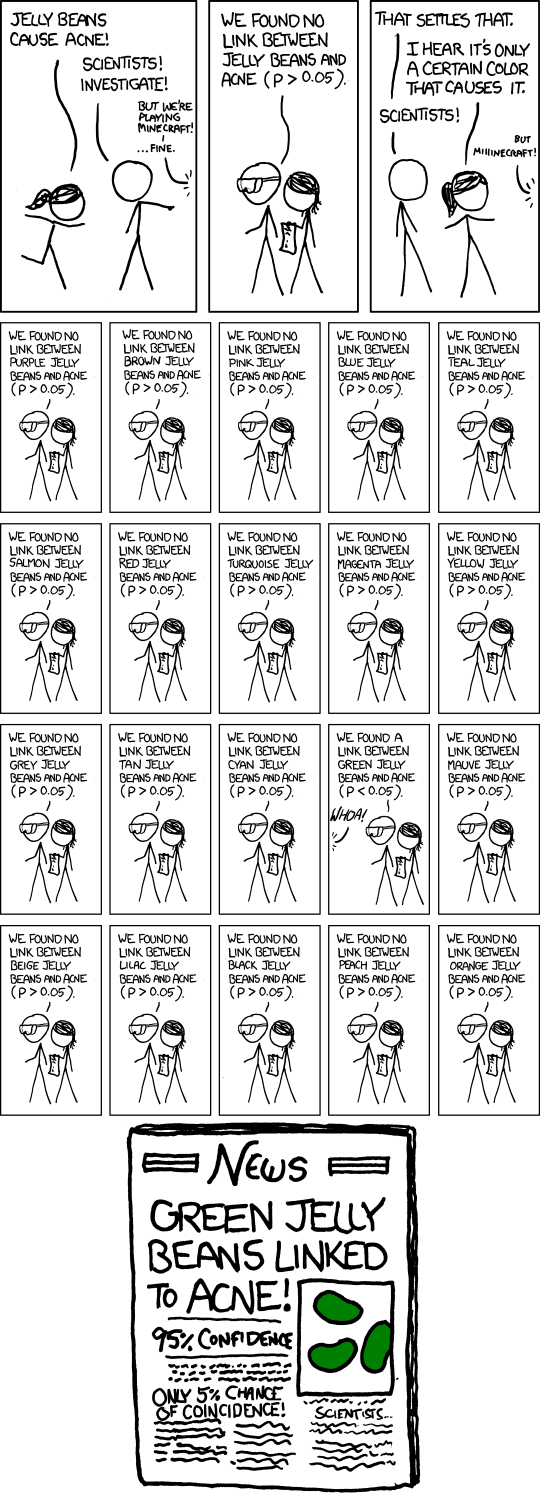

This is an approach known as "outcome switching" or "subgroup analysis". If you want to know why it can be a problem, this XKCD comic sums up the issue very well:

Essentially, the more different ways you divide your data up, the more likely it is that you'll find something that looks interesting just by chance. That's why it's important that scientists declare in advance what they're looking for, and make it clear if they change it.

The outcome switching looks particularly suspect in this case, because the researchers didn't compare the group being studied to the patients who took placebos and no other drugs – as you might expect – but to the entire placebo group.

Discussing the trial's findings, Claude Wischik, the co-founder of TauRx, told Forbes magazine, “I don’t believe it is a chance finding," saying the result was repeated in a second trial. However, the data from that trial has not been made available to the public.

Some scientists are unimpressed with coverage of the study.

Furthermore, to get this "positive" result, in a subset of *15%* of patients, they had to use a freaky control group https://t.co/xYlpicegy3

Chris Chambers, a professor of cognitive neuroscience at Cardiff University, told BuzzFeed News that it's possible the result is "a false discovery resulting from cherry-picking data".

"Registered primary outcome measures should form the basis of any conclusion," he said. "Any subgroup analyses should be strongly caveated, if reported at all.

"This is a perfect storm of public relations hype combined with journalistic hype, resulting in headlines that ultimately mislead patients. This really quite egregious.

"What is the primary mission of medical reporting if not to report the outcomes of these trials as accurately as possible? There is only one actual truth in this case and that is that the study returned a negative result."

Ben Goldacre, a medical doctor and campaigner for scientific openness, says outcome switching is a major problem for science.

He told BuzzFeed News for an earlier piece: “If you measure a huge number of outcomes, and then allow yourself to pick and choose which you will report as your main finding, then suddenly the scientific integrity of your study is in big trouble.”

Goldacre leads the CEBM Outcome Monitoring Project, aka Compare, part of Oxford University’s Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, which campaigns against outcome switching in scientific research.

Alzheimer's Research UK's chief scientific officer told BuzzFeed News he was "hopeful, but sceptical".

Dr David Reynolds said cherry-picked data was "certainly one interpretation" for the results. "When the trial's endpoint hasn't been met, choosing a subgroup with 15% of the patients makes it much more likely that there'll be some sort of bias that affects the results," he said.

"It's scientifically hard to understand why this drug would only work on its own, without other Alzheimer's drugs, and no plausible explanation has been given.

"I'd love to think this was something important, and that we were making headway, but I've seen lots of these subgroup analyses and when they're tested later in a proper trial they don't stand up. It needs a new trial, just looking at the drug on its own."