Bacteria are increasingly capable of resisting the drugs we use to kill them.

It's a problem of evolution. Using antibiotics kills almost all of the bacteria in a patient. But the ones that survive tend to the ones that are best able to resist those antibiotics.

Those hardy survivors then breed, and the next generation of bacteria are a bit more resistant to the antibiotic than the generation before it.

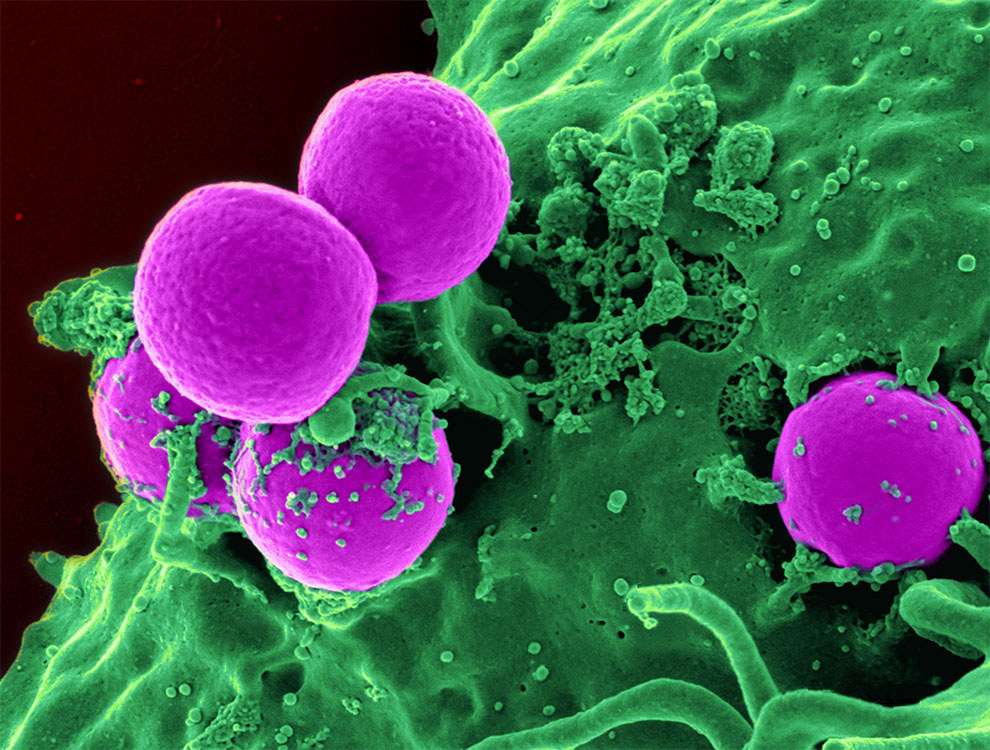

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is probably the most famous superbug, but drug-resistant strains of tuberculosis, gonorrhoea, E. coli, and others are all common. The Centers for Disease Control in the US have a list of the 18 biggest drug-resistant threats.

One kind of bacteria, "gram-negative" bacteria, is particularly hard to fight with antibiotics.

That's why there is cautious excitement about a study, published today, that seems to reveal an "Achilles heel" for these bacteria.

The research could lead to whole new classes of antibiotics, according to its authors.

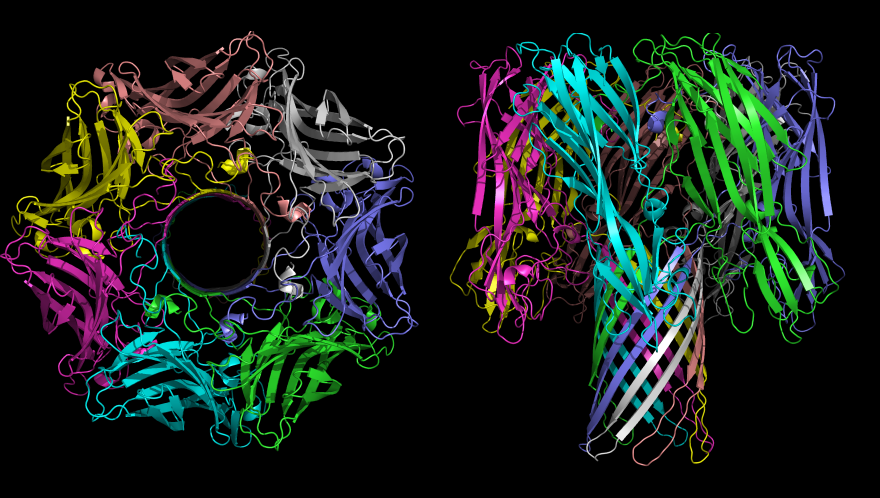

Professor Changjiang Dong of the University of East Anglia, the lead author on the study, told BuzzFeed News that these proteins are "crucial" to the bacteria: "If we can break this cell wall [process], we can kill the gram-negative bacteria." And because one of the proteins is outside the cell wall, it means drugs that target it don't have to get through that wall first.

Dong said that "in a few years' time – less than 10 – we could create a compound that would kill the bacteria". Now that the structure of the beta-barrel proteins is known, he said, drugs can be made that attach to the shape of that protein and disrupt its working.

He also said that these new drugs would also be more difficult for bacteria to learn to fight off. Because the drugs attack the bacteria's defences, he said, the bugs will find it harder to develop resistance, although they may find a way eventually.

Other experts are optimistic about the study's findings, although they warn against getting too excited.

It's particularly interesting, one scientist said, because it's a new way of looking at the problem.

"This isn't the old-fashioned 'grow bugs and see what kills them' approach," Dr Colin Davidson, a biotechnology researcher at Cambridge University, told BuzzFeed News. "It's the first step towards maybe finding new families of drugs.

"Cell wall proteins are really hard to study, because they're not easy to crystallise and purify. So any deeper understanding that comes from this kind of imaging really does give us clues to how we might design new drugs targeting these proteins." He agreed, though, that new drugs were "a decade or more" away.

There are huge obstacles to overcome in developing any drugs.

Garner pointed out that the BAMA protein is also present in human cells. Mitochondria, the little energy-producing organelles inside each of our cells, are all descended from bacteria. "We have to be sure that our mitochondria wouldn't be damaged [by a drug targeting BAMA], that only the bacterial cells are," he said. "Otherwise there's a possibility that the drug would be toxic to humans."

Also, the researchers have only looked at one species of bacterium, E. coli. "There are at least four species of gram-negative bacteria that cause problems," Garner said. "They haven't shown that those other ones have the same complex in their cell walls." If they don't, though, he says, this could still lead to antibiotics targeted very precisely at E. coli, which would be important in itself.

And as exciting as it could be, even if new drugs are developed, it will just be kicking the problem down the road if the way we create and use antibiotics isn't radically changed.

"It's not that we have a single problem," said Jinks. "There are multiple problems that, together, create what is threatening to be a crisis."

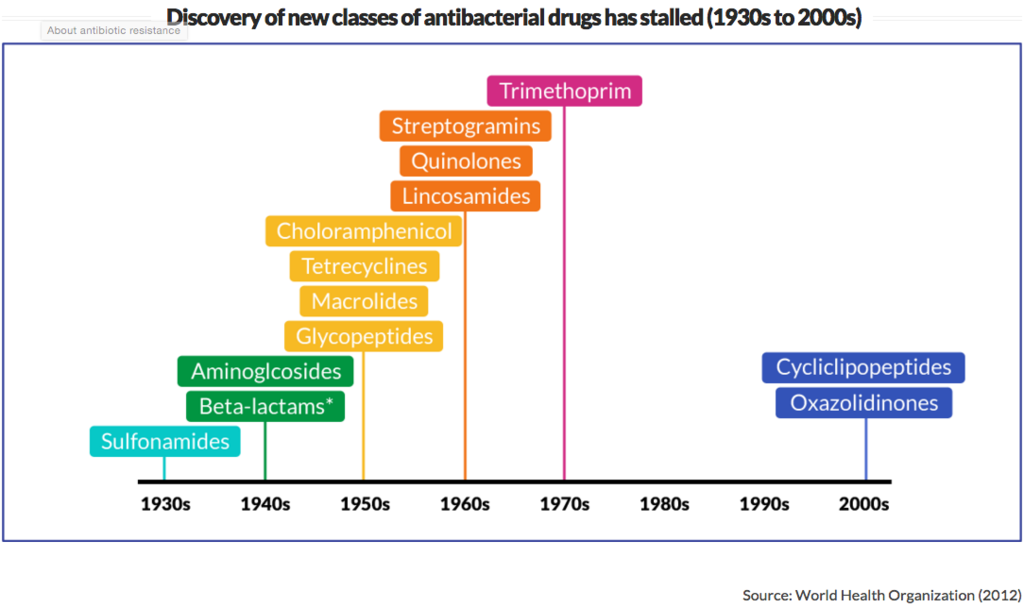

One problem is that we've stopped making new antibiotics.

And another problem is that we're using the antibiotics we do have in profligate and dangerous ways.

One way people can help fight against drug-resistant bacteria is to make sure they know what antibiotics can and can't do.

Many people don't understand what antibiotics are for, or that they only work on certain diseases, so they demand them for illnesses even when they'll do no good. "People will need to better understand the risks of using antibiotics," said Jinks.

That's starting to happen, he said, but "we've gone through an era which has taken these medicines for granted, and we need to make sure that these limited resources are treated with care".