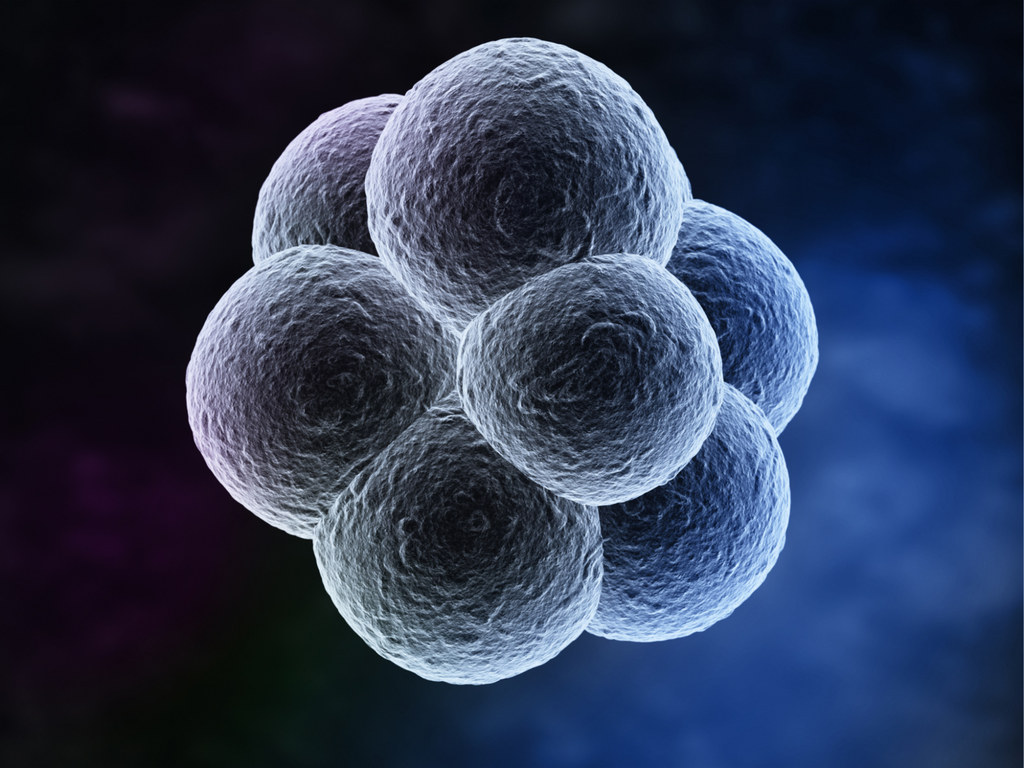

Scientists in the UK have been given a licence to edit the genes of human embryos.

However, this doesn't mean that the research can now go ahead.

There is another hurdle – ethical approval of the study itself. But the granting of a licence is a key step.

The team will use a new genetic modification technique called CRISPR, which allows very specific edits to be made to genomes.

The research could help develop treatments for infertility.

A better understanding of what makes embryos succeed or fail could mean new hope for would-be parents who are struggling to conceive, said Griffin.

It could also help research into stem cells, which could lead to other medical breakthroughs.

Britain is ahead of the world on research like this.

CRISPR is a genetic technique used by bacteria to defend themselves against viruses.

When a virus invades a cell, the bacterium can cut out a section of the virus's DNA and store it in its own genome, so that it will recognise that virus in future. By using the same technique, scientists can now cut out specific genes and insert them, very accurately, into the genome. "In simple terms it's like a pair of scissors that cuts out the gene and replaces it with another one," said Griffin.

Previous techniques were much less accurate, Griffin said: "You don't really know if it's going in the right place, so you don't know if your edit is precise enough." CRISPR has made gene editing much faster, more accurate, and cheaper.

This licence absolutely does not mean that scientists can create genetically modified babies.

It also doesn't mean that any human embryos will be created and destroyed just for this research.

All embryos used in research in the UK are surpluses from IVF treatments, and would be destroyed anyway if they weren't used in research.

Not everyone is happy about it, though.

Critics warn of a "slippery slope" towards designer babies. "This is the first step on a path that scientists have carefully mapped out towards the legalisation of GM babies," David King, director of Human Genetics Alert, told the Financial Times.

Griffin said that these concerns "aren't necessarily a bad argument", but "it's less important when you have a good regulator, as we do". Nonetheless, he said, "it's very important that we consider it ethically as well as scientifically".