The importance of our microbiome, the population of microscopic organisms living in our bodies, has gained attention in recent years.

Trillions of bacteria – and other tiny single-celled organisms, such as archaea and protozoa – live in our bodies, largely in our gut. They're estimated to outnumber the actual cells of "our" bodies.

This ecosystem of tiny creatures we carry around with us is thought to have profound effects on our health.

The Human Microbiome Project says that the makeup of an animal's microbiome has an impact on its immune systems, heart health, and behaviour, among other things.

It's thought that early life events – notably birth and breastfeeding – might affect our microbiomes.

People who are born by caesarean section seem to be slightly more at risk of obesity, asthma, and some immune conditions. It's thought that being born vaginally exposes the child to the mother's microbes. It's a similar story with breastfeeding.

Now a new study has found that the effects of these early events don't last as long as previously thought.

The Flemish Gut Flora Project (FGFP) looked at the intestinal microbiomes of more than 1,000 people. The results were published in the journal Science. "We studied the microbiota of adult individuals in Belgium," Dr Jeroen Raes, one of the study's authors, told BuzzFeed News. "It's one of the largest studies worldwide."

The study found found no difference in the diversity of the microbiomes of adults who'd been born via caesarean and adults who hadn't. Similarly, breastfeeding seemed to make no difference.

"There's very little evidence that the microbiota was different in adult age," said Raes. "We were surprised by that. Everyone assumes your microbiota is determined at birth, but we didn’t see that."

Dr Julian Marchesi, a biochemist at Imperial College London who works on the human microbiome but was not involved in this study, told BuzzFeed News that the results make sense: "I know that [early-life events] have an impact in the first couple of years of life, and maybe the first five years. But when you get on to solids, and start interacting with other people, it seems like early life events get wiped out."

That's not to say that these things have no effect on your health, though.

It's still very possible, said Raes, that early-life events can still affect your health in important ways. "This result doesn’t mean that they don't have a strong effect at a young age, when you’re a baby," he said. "And that could maybe have long-term effects on your health and your immune development."

Marchesi agreed, although he said that more research is clearly needed. "We’re struggling to find out the consequences of early life events on later life," he said. "Autoimmune diseases seem to be impacted by the microbiome, and how the body reacts to infection.

"But that early-life window, we don't know the significance of it for cognitive development, immune development, and so on."

The list of things that do seem to affect our adult microbiome is pretty interesting. The drugs we take, for instance.

People on amoxicillin, an antibiotic, had a less diverse microbiome. "The use of drugs is important," said Raes. "Taking medication, e.g. laxatives and antibiotics, affects your microbiome. Hormones as well. That’s interesting because there’s been very little research on this before now."

And it's related to the kinds of poos we do.

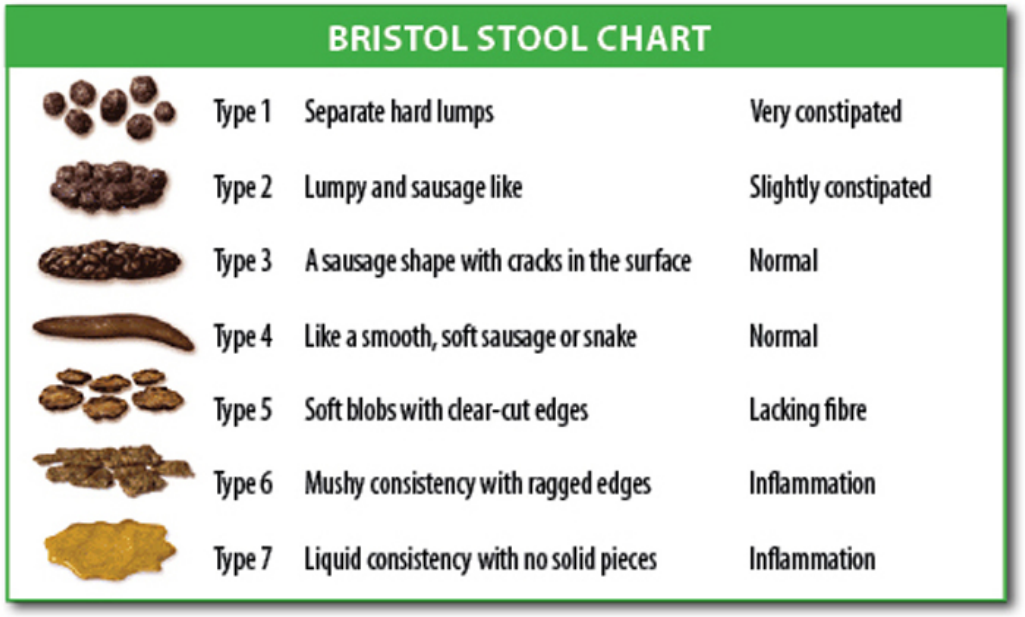

The study found that people's scores on the Bristol Stool Chart – a seven-point scale ranging from 1 ("separate hard lumps, like nuts") to 7 ("watery, no solid pieces") also predicted the diversity of their gut flora, with higher scores generally meaning lower diversity.

This matters, because microbiomes might act as an indicator of our overall health.

"The reason this is so important is that the microbiome could be used as a future diagnostic," said Raes. "It could allow the diagnosis of autism, Parkinson's, Crohn's."

For instance, he said, there are some indications that Parkinson's disease is associated with a certain kind of bacterium in the gut, so if you detect that bacterium, that might be an early warning of Parkinson's. "But Parkinson's is associated with constipation," he says. And constipation affects your gut flora, so maybe that's the link.

That means it's important to know what a normal, healthy microbiome looks like. And so far, we don't.

This study has taken steps towards doing that – "characterising the core microbiota", as it describes it – and found more than 600 families of bacteria. But it hasn't yet worked out the whole set.

"It is one of the major research questions we were after," said Raes, "and to my frustration we haven't answered it. I was hoping to be able to say 'The healthy microbiome looks like this,' but it wasn’t so simple." The FGFP is carrying on, and will look at another 3,000 people, so he hopes that more details will come out of that.

Marchesi added that there probably isn't a single healthy microbiome. "You’ve got to think of it like heart output or lung output," he said. "It’s not a one value, there’s a spectrum, just like there’s no one good value for blood pressure."

He also said that studies so far have largely focused on white Westerners. "The other thing we’re struggling with is we don’t know much about non-white, non-European, non-American guts," he said. "What we see in this might not play out with a Chinese or an African or an Australian Aboriginal gut."