Despite a great deal of recent concern, moderate amounts of "screen time" – how much time they spend using technology with screens, such as computers, TVs, and smartphones – is not harmful and may, in some cases, be beneficial to young people's mental wellbeing, according to a new study.

The research, published today in the journal Psychological Science, looked at the screen habits of 120,000 English 15-year-olds, breaking it down into watching TV and movies, playing video games, using computers, and using smartphones.

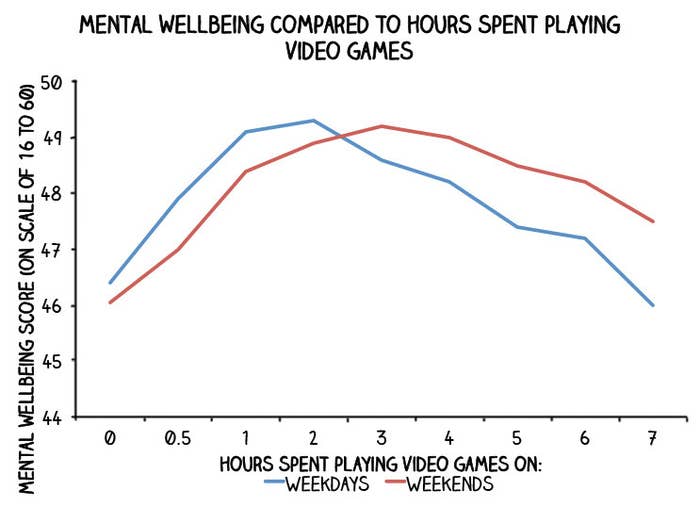

It found, for example, that teenagers who watched TV for four hours a day on weekdays, or seven hours a day at weekends, on average scored the same on a measure of mental wellbeing as those who watched none at all. The findings were similar for recreational computer use, while those who played video games for up to six hours on a weekday (and longer on a weekend) showed no ill effects. For smartphones, it was shorter, about two and a half hours on weekdays and three hours at weekends.

What was noteworthy, however, was that teenagers who used the technologies for less than the times just quoted actually scored slightly higher on the mental wellbeing measure than those who didn't use them at all.

When teenagers played or watched for longer, the study found that mental wellbeing started to decline. However, this effect was small. "Even at exceptional levels, we’re talking about a very small impact," Dr Andrew Przybylski, a psychologist at Oxford University and one of the study's authors, told BuzzFeed News. "It’s about a third as bad as [the effect on wellbeing of] missing breakfast or not getting eight hours' sleep."

Dr Pete Etchells, a psychologist at Bath Spa University who did not work on the study, told BuzzFeed News that the work is "a really nice study for a lot of reasons".

"'Screen time' is usually a bit pointless as a measure," he said. "It loses so much nuance, and this study is trying to break it down a bit, by TV and video games and so on, and the really simple idea of breaking it down by weekend vs weekday."

He said that the public debate usually focused on the idea that the more people use "screens", the worse it is for their health. "There's more and more data showing that that's simplistic," he said.

Both Etchells and Przybylski stressed that the study did not prove that screen time caused either the positive or negative effects, just that the two were linked. "It’s very difficult to infer a causal direction [from this kind of study]," said Etchells. "It could be, if you see a negative correlation, that screen time causes a reduction in wellbeing, or it could be that people who are experiencing a drop in wellbeing turn to their smartphones more often."

To be sure about what causes what, he said, you'd need to do a randomised control trial, "and you'd need huge sample sizes and lots of money".

He also praised the study for its rigour and openness. Science in general and psychology in particular has been undergoing a "replication crisis" recently, in which the findings of many influential studies have been called into question when other scientists were unable to reproduce them.

Part of the problem has been that some studies change what they are looking for after the data comes in, which makes it easier to find apparently significant results. Some researchers, including Przybylski, have been campaigning for studies to register their hypotheses and methods in advance, to avoid this "bait-and-switch". The screen time study was preregistered, and all its data has been made available online. "That's exactly what this area of science needs," said Etchells.

The perils of "screen time" have been in the news lately. Over Christmas, a group of prominent educators and scientists wrote to The Guardian calling for "national guidelines on screen use". Another group, including Etchells and Przybylski and the Harvard professor Steven Pinker, wrote a few days later, saying that the first letter's arguments were "simplistic", "divisive", and "scaremongering" and calling for any guidelines to be "based on evidence, not hyperbole and opinion".

"It goes back to this idea that as screen time increases, physical activity decreases," says Etchells, "and there’s a lot of research that shows they’re unrelated. It’s a more complex story."