In the last few years, scientists have been actively campaigning to make their own jobs harder, and to make their research less likely to come back with the results they're looking for.

Scientists and campaigns in Britain and the US have been calling for researchers to "tie their hands", to prevent them using conscious and unconscious tricks to make their studies look better than they are.

Under normal circumstances, when a study is published in a journal, there is no record of what the researchers were originally looking for. That allows the researchers, deliberately or otherwise, to manipulate the data, say critics.

But if the hypothesis and methods of a trial are registered in advance – if it is clear what the scientists were expecting to find and how they were going to look for them – then the statistical tricks that can set in are avoided.

This can have serious, real-world consequences. In July the media got excited about a study that they said showed "glimmers of hope" in the search for a treatment for Alzheimer's.

But the results of the study, as a whole, were negative. It was only by digging into a small subset of the data that the researchers were able to find something that looked positive.

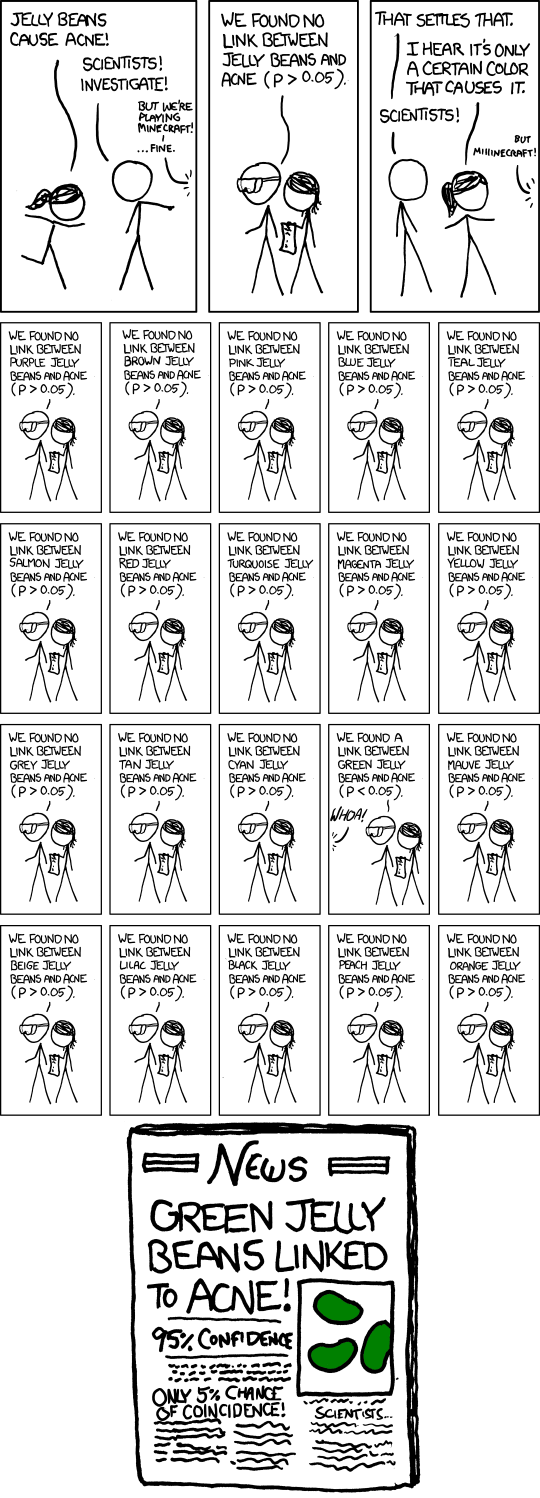

This XKCD comic explains how:

Preregistration prevents that sort of cherry-picking of data, Chris Chambers, a professor of neuroscience at Cardiff University who is behind the Centre for Open Science’s Registered Reports movement, told BuzzFeed News: “It ties researchers’ hands and keeps them honest.”

Dr Andrew Przybylski, an experimental psychologist at the University of Oxford, said there is “an inbuilt conflict of interest” in scientific publishing that pushes researchers and journals towards only publishing research that finds exciting, positive results.

"Preregistration ties researchers’ hands and keeps them honest."

This encourages bad practices. For Przybylski’s latest research, published today, looking at the impact of “internet gaming addiction”, he attempted to avoid them by registering his hypotheses and methods before the beginning of the trial.

The ways unregistered trials can be manipulated are subtle but profound, says Chambers. “Researchers can start out looking for outcome A, but end up reporting on outcome B because it shows a more attractive result,” he says.

The effect is like firing a machine gun at a barn wall then drawing a target around the bullet holes and saying you’re a good shot, he says – the “Texas sharpshooter fallacy”. “HARKing”, or “hypothesising after the results are known”, is another risk – creating post hoc theories by combing through the literature to fit data you already have. These statistical tricks increase the likelihood of getting a result you want, and so make the scientific literature less trustworthy.

It affects all of us, says Przybylski. The American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) recently issued guidelines for how much screen time you should allow your child. “One of the articles they cite ran 96 stats tests, and only five of them gave a significant result,” he says.

“And those are the five they report. Parents have very little bandwidth for this stuff, when you’re trying to work out whether you should be fighting to prevent one more episode of Peppa Pig.”

"Unless you’re transparent about why your outcomes changed, it’s bad science."

The study of internet addiction, the subject of his own latest research, is a field full of poor practice and high stakes, he says. “There are a number of ‘gaming addiction’ clinics in China, where parents pay thousands of pounds a month to cure their kids’ addiction, and sometimes the kids actually die,” he says.

“And it’s all based on very low-quality research done in the West. One study says 46% of young people are addicted to the internet; another says 5%. This is our attempt to bring this kind of rigour to a controversial topic.” His own research suggests that just 1% of users suffer from something characterisable as “addiction”, and that this problem has fewer health effects than, for instance, the much more prevalent gambling addiction.

By preregistering results, any changes to your outcomes or your hypotheses are obvious, says Chambers. “It’s not designed to stop you changing your hypothesis or your analysis," he says. "You might have a very good reason for doing so. But unless you’re transparent about why it changed, it’s bad science.”

"We don’t just see the most perfect result, but also the others that aren’t as perfect."

Registered Reports encourages journals to promise to publish research if its hypothesis and methods are preregistered and peer-reviewed, to avoid the incentive to sex up results when they come in. A total of 28 journals, including Cortex and Experimental Psychology, have signed up to it, and the Centre for Open Science is offering cash prizes to researchers who publish preregistered trials.. And a study this year found that preregistered trials are much less likely to show positive results.

Journal editors are increasingly looking for studies to be preregistered as a way of guaranteeing their quality, says Simine Vazire, an associate professor of psychology at the University of California, Davis, who holds editorial positions on various journals. “Researchers can make the case for making changes – dropping outlying results, or changing the statistics you look at,” she says. “But without preregistering, you don’t know if that was the case all along.

“Preregistering requires authors to be transparent, so we don’t just see the most beautiful, perfect result, but also the other results that aren’t as beautiful and perfect.”

More should be done to encourage preregistration, she says. “We should make it a major factor in our editorial decisions. If a trial is preregistered, it should have much more weight than if it isn’t."

All this has real-world consequences, according to Chambers and Przybylski. “We know from our own work that preregistration prevents mistakes,” says Chambers. “We did a brain imaging study that took over a year, with a detailed preregistration.

“When we started analysing the data, a student came and said she’d found something really interesting, something that made sense, considering previous literature. So we assumed we’d preregistered it – but it turned out we hadn’t.

“If we hadn’t preregistered, we’d have assumed we predicted it, and written a paper saying we predicted it. So without any conscious act of fraud, we’d have undermined the scientific process – we’d have fallen to bias. But now the reader knows it’s a post hoc finding.”

CORRECTION

Simine Vazire is an associate professor at the University of California, Davis. An earlier version of this piece misstated the university at which she works.