On 11 March 2011, a huge earthquake struck off the northeastern coast of Japan, sending a vast tsunami speeding towards the shore.

There was huge devastation from the quake and tsunami, and at least 15,900 people were killed.

But, in the West at least, the disaster is best remembered because of the damage to a nuclear power plant called Fukushima Daiichi.

Fukushima had a huge psychological impact around the world.

Polls in Europe and the US found that support for nuclear power had suddenly dropped. Germany started phasing out its own nuclear power plants immediately after the disaster.

Even now, the event colours perceptions of nuclear power. This month Greenpeace released a report, Nuclear Scars, on the "lasting legacies of Fukushima and Chernobyl", that ties in with the anniversaries of the two disasters (Chernobyl happened 30 years ago next month). "The long-lived nature of radioactive contamination means the consequences of these disasters will be with us for decades and centuries to come," the report says. "We have an obligation to ourselves, our children and the planet to ensure we never see such destruction and misery ever again."

However, scientists are concerned that the focus on Fukushima and radiation has taken our attention away from the real human tragedy of Tōhoku.

They say that despite the public alarm, not a single person has been killed by radiation from Fukushima.

"There was a lot of death and destruction [from the earthquake]," Jorgensen said. "I think over 16,000 people died. But the focus has largely been on radiation casualties, and the fact of the matter is that there haven't been any radiation casualties.

"The focus on the radiation has been disproportionately high."

They also say that the radiation hasn't caused anyone to develop cancer, and it won't in future.

Thomas said that for "the vast majority" of people in the area, the dose of radiation they received from the leak was no more than they'd get from having a CT scan. "Cancer risks in Japan have not been affected by the radiation," she said. "The individual doses from Fukushima are extremely low."

"You wouldn't expect to see measurable increases in cancer rates," agrees Jorgensen. "The levels of exposure are so low."

Even among the cleanup workers, the risks are very low.

In fact, the fear of radiation could do more health damage than the radiation itself.

Evacuation has been bad for people, says Thomas: "The changes in lifestyle brought about by the evacuation have led to a small increase in weight gain, and associated diseases: hyperlipidaemia, raised blood pressure, diabetes."

In a sad irony, weight gain is associated with an increased cancer risk. "If this leads to a long-term change in lifestyle, it might increase overall cancer risk in a small proportion of the population," she says.

The Fukushima reaction is evidence, she says, that "there is a greater effect on health from the fear of radiation, and how this makes us respond in an emergency situation, than from the effect of the radiation itself".

For instance, thousands of evacuees died in temporary shelters.

An overreaction to the risks of nuclear power could make it harder to fight climate change as well, they say.

"The issues from global warming colour this debate," says Jorgensen. "Are we going to commit ourselves to fossil fuels and all the problems inherent in that decision? There are risks to nuclear power, but there are also massive benefits."

Thomas agrees. "Having nuclear power in a country's energy mix increases energy security, and decreases CO2 emissions when coal, oil, and gas plants are reduced," she says. "Climate change will have a substantial impact on health, so it is important that we balance the risks and benefits."

The scientists say the reaction was partly sparked by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) bracketing Fukushima alongside the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Partly, it's because the public is afraid of radiation in general.

"It has this mysterious quality, and people just tend to be petrified by it," says Jorgensen. "You can't see it, you can't smell it, you can't taste it, but you know it's out there."

And partly, they say, it may have been because of media overreaction.

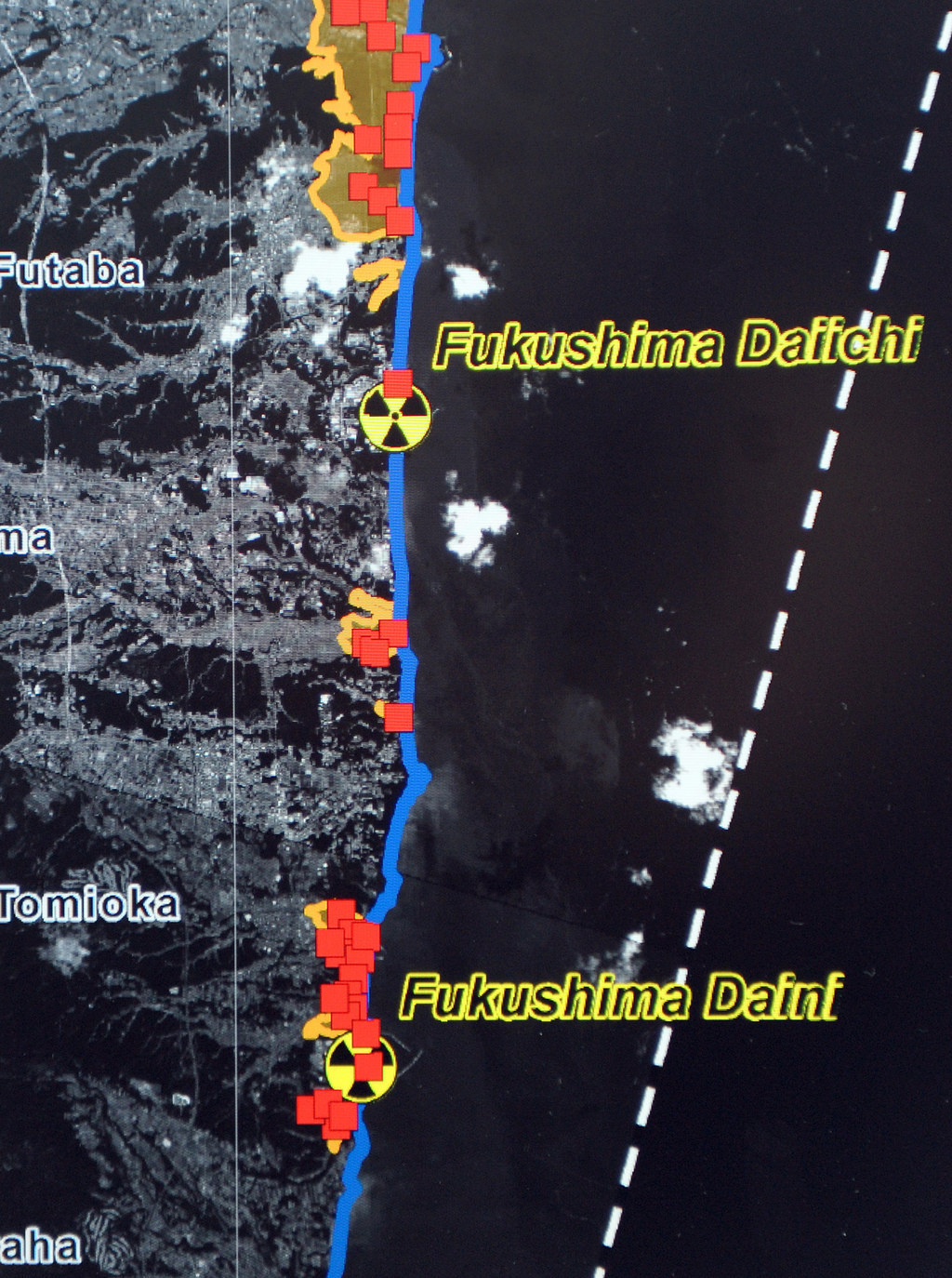

There are lessons to be learned from Fukushima, they say. One is how to design nuclear power plants on coastlines.

The water from the tsunami came over the top of the sea wall that was designed to protect it. "The height of the sea wall was built to be sufficient to protect against the tsunami from an earthquake that hit Japan in the 1960s," says Jorgensen. "There were bigger tsunamis that happened hundreds of years ago, but no one remembered them."

But the mistake was not necessarily that the sea wall ought to have been higher – "the costs would have been prohibitive" – but that the builders assumed it would always hold. "With that assumption, they did things like put the electrical batteries and systems in the basement of the reactors," he says.

"Everyone who has a home knows that basements occasionally get flooded. That could have easily been altered, and would have prevented a catastrophe even if the walls had been breached."

Another is that immediately evacuating people in the event of nuclear accidents isn't necessarily the right thing to do.

And finally, governments should be honest with the public about the risks and let people make up their own minds.

Jorgensen says that the current policy of arbitrary "safe levels" of radiation is unhelpful. "Before the accident, the limit for annual exposure to the Japanese public was set at 1mSv above background levels." Background levels in Japan are about 3mSv.

But after the accident, it was obvious that getting exposure back down to those levels was unrealistic, so the government changed its limit, to 20mSv annually. "So people say: 'Wait a minute, you told us 1mSv was the safe limit, and now you're saying 20 is safe? Something funny is going on here.' It breeds distrust."

Instead, the government should just make it clear what the increased risks are, he says. That 20mSv is about the equivalent of two CT scans, or one whole-body scan. "These are the types of levels we're talking about," he says. "I think the Japanese government would be best served to just explain the risk levels to people and let them decide for themselves whether it's worth it to go back here."