There's a lot of stuff in the papers today about the Department of Health planning to force patients to show their passports if they want to get treatment on the NHS.

The NHS provides treatment free to everyone resident in Britain. But nonresidents, in theory, have to pay for most nonemergency treatment. If they're citizens of the EU, or of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway or Switzerland, the cost is paid by their nation's governments.

Countries such as Australia and New Zealand have reciprocal agreements, and citizens of other countries have to pay themselves, usually via insurance.

But the government has been concerned for some time that the costs of overseas patients are not being retrieved, hence the passport check idea.

Some hospital departments already do it, such as the maternity ward at St George's hospital in Tooting. But the DoH's top civil servant, Chris Wormald, said the scheme could be extended nationwide.

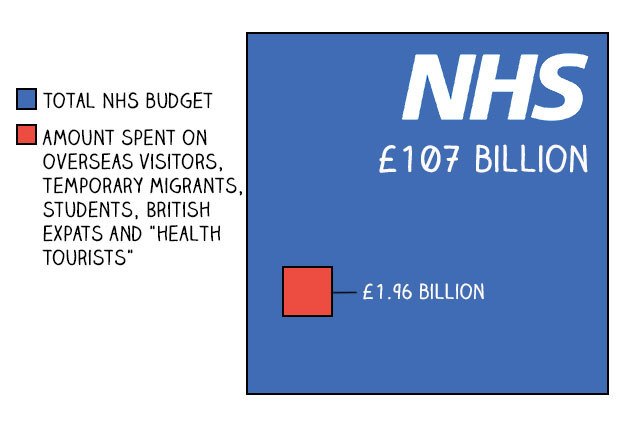

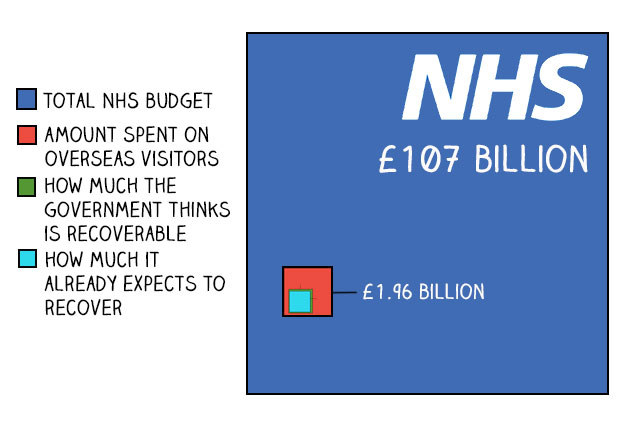

Exactly how much the NHS in England spends on treating overseas patients isn't exactly clear, but in 2013 the government estimated that the figure came to just shy of £2 billion.

That's obviously a lot of money, but when you put it in the context of the total NHS budget – which this year is £107 billion – it's not such a big deal:

Still, it's not nothing. But you can break that figure down further.

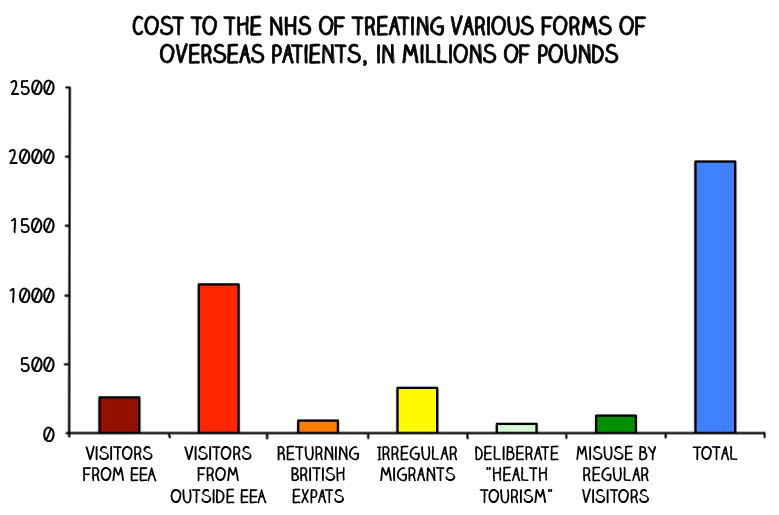

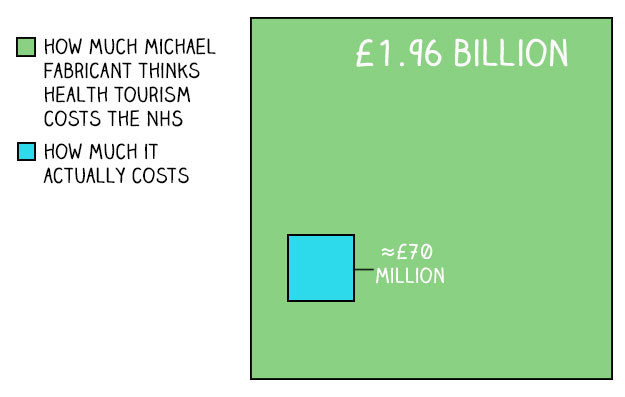

The phrase that gets bandied around a lot is "health tourism". That's when people specifically come to Britain to get treatment on the NHS to which they are not entitled, according to John Appleby, a professor of health economics at the Nuffield Trust. "That's a very small group," he told BuzzFeed News.

As you can see in the graph, "health tourism" only makes up a tiny fraction of the total spent on overseas patients – between £60 million and £80 million, according to the DoH's estimates. (We've used a central estimate of £70 million for the chart.) Other misuses by overseas visitors taking advantage cost between £50 million and £200 million (we've used a central estimate of £125 million).

The overwhelming majority of the £1.96 billion – a total of £1.76 billion – comes from "normal" use of the NHS, although it should be noted that that includes an estimated £330 million on irregular, or, if you prefer, "illegal", migrants.

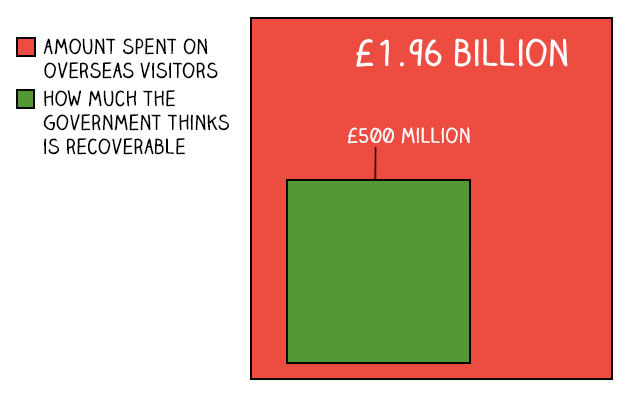

So how much of that can we actually get back?

Good question, and the answer is essentially "we don't know". For a start, A&E treatment and GP visits aren't (currently) subject to repayment.

Further, some migrants and visitors are entitled to free healthcare under certain circumstances: "These rules are complex," according to the DoH report. For instance, says Appleby, "you wouldn't want to charge someone who's got typhoid, you'd just want to get them treated" – because if you charge them, they might not show up, and then they're a public health risk. So treatment for some infectious diseases is exempt.

It's also complicated finding out exactly how much is paid back, because under the agreement between EU countries, bills don't have to be paid the same year they were received.

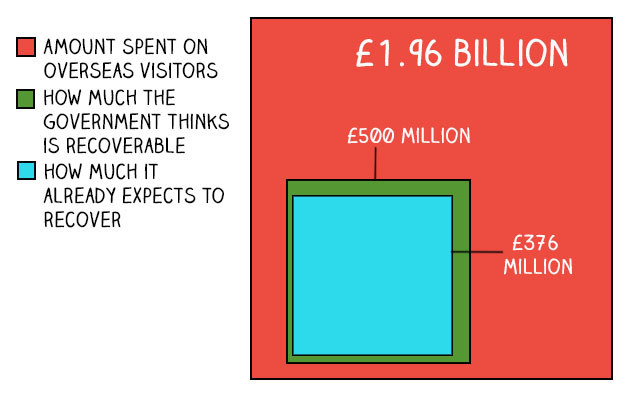

So it's not really clear. But in short, the government estimates that about a quarter – £500 million – of the £1.96 billion spent is legally recoverable.

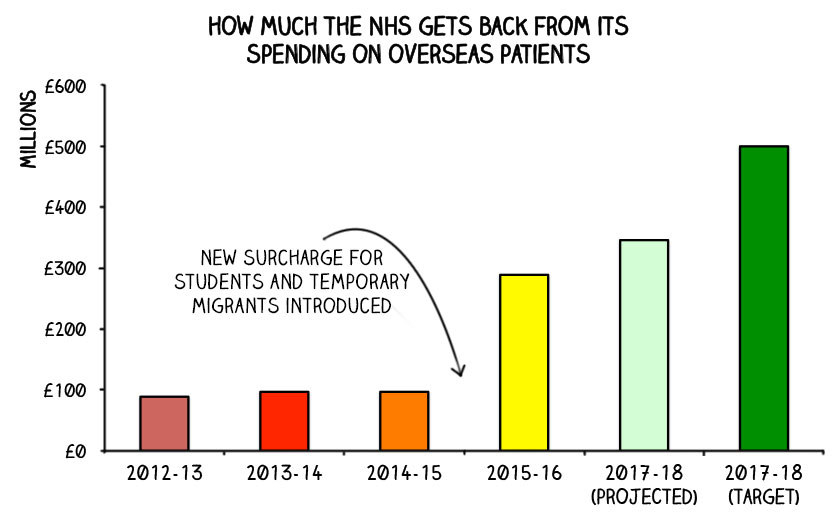

In fact, it's not doing too badly at getting it back already.

That wasn't true until recently. Just £89 million was reclaimed in the financial year 2012-13, according to the National Audit Office (NAO)'s estimates; that figure rose to a not-much-more-impressive £97 million in 2013-14 and 2014-15. But in 2015 the rules were changed, meaning that overseas students and temporary migrants no longer received free care. The amount retrieved immediately trebled to £289 million in 2015-16.

The NHS has set itself what the NAO calls an "ambitious" target of getting the whole £500 million by 2017-18, and according to the NAO's projections will fall short – it's on target to get about £346 million. But that's still almost four times what it was getting just three years ago.

So will forcing people to show their passports change things very much?

Not really, according to Appleby. Health tourism is a "minute" problem, he says: "It's a minute amount of money.

"I have a feeling the public doesn't understand the proportions involved; people speak as though thousands and thousands of people are doing it, but they really aren't."

He draws a parallel with a law that says that hospitals can charge people injured in road traffic accidents for their care, introduced in the 1960s: "Hospitals looked into it and found it wasn't worth doing, because of the costs of bureaucracy." Forcing patients to show a passport and a household bill could be a similarly disproportionate response, he says. It might, he thinks, have an impact on patients seeking to come here, but that's about it.

And it can't have all that much of an effect on other overseas-patients costs, because there isn't all that much to have an effect on:

And remember, in the context of the overall NHS budget, that looks even smaller:

So, probably, passport checks won't do very much to solve the NHS's budget crisis.

One last point. Whatever the rights and wrongs of passport checks, one thing that is DEFINITELY wrong is this:

Deliberate Health Tourism (visitor comes with MRI scan from abroad and demands treatment) costs #NHS >£2bn each year. We must stop this!

CORRECTION

There is no reciprocal health agreement between Canada and the UK. An earlier version of this article said that there was.