Tyrannosaurus rex, one of the largest land predators ever to have lived, could not have broken into a run without its leg bones shattering, according to new research.

The findings imply that T. rex wouldn't have been been a high-speed pursuit predator, and would probably have killed its prey either by ambushing them or by engaging in long, slow races with other less-than-athletic dinosaurs.

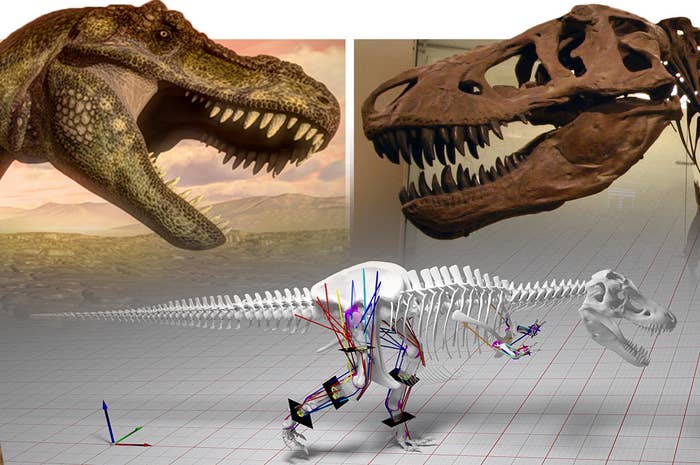

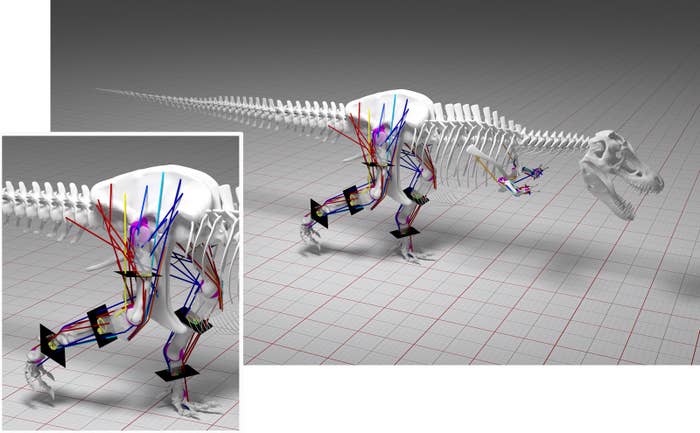

Researchers at the University of Manchester created a detailed anatomical computer model of the 7-ton dinosaur to calculate the load on its skeleton at various speeds and gaits. They found that its skeleton was perfectly capable of moving in a run – defined as having both feet off the ground at the same time – but if it had ever actually done so, its bones would have shattered. The study is published in the open-access journal PeerJ.

"This is a really nice analysis of how [T. rex] would have moved," Paul Barrett, a professor of palaeontology at the Natural History Museum who was not involved in the study, told BuzzFeed News. Some previous estimates had suggested the dinosaur was capable of speeds of up to 45mph; that's partly because it has long, slender leg bones. "These are features associated with fast running – ostriches, gazelles – so it wasn't an unreasonable assumption to think it was a fast runner."

But that view has slowly been starting to shift in recent years. "A number of my colleagues have previously thought that it wasn't a sprinter – there's a growing body of evidence that it wasn't a super-fleet athlete – but this is a new technique, looking at how the movement would have affected the animal's skeleton."

William Sellers, a professor at the University of Manchester's School of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the leader of the study, told BuzzFeed News that "there was no way you could get it to a running gait" without the bones breaking. "Bone doesn't change very much and hasn't for a long time," he said. "Whenever we reconstruct a fossil animal the bone is more or less the same as its modern relatives." That means they could be fairly confident about the strength of the bone, and therefore the loads it could take without breaking.

The top speed T. rex was capable of was about 20km/h (12mph), said Sellers. That's a fast jog for a human being: about the pace that professional marathon runners maintain for 26 miles. "It had long legs, so it was a fast walker," said Sellers. But a healthy young human would absolutely have been able to outsprint it over short distances.

What that means is the popular image of T. rex as a pursuit predator, chasing its prey in bursts of speed like a modern lion or cheetah, is "dead in the water", said Sellers. "It's much more likely to be an ambush predator, waiting for these things to come along," he said.

The idea of a 7-ton, 40-foot-long dinosaur hiding behind a tree waiting for someone to come along may seem incongruous and faintly comical, but both Sellers and Barrett pointed out that they probably lived in densely forested areas, where even big animals can hide surprisingly easily. "You only have to talk to people who’ve done fieldwork in forested areas, and they’ll tell you you can suddenly come across an elephant," said Sellers.

Another alternative, according to Barrett, was that T. rex did chase its prey – but slowly. "Lots of the large animals that T. rex chased would have been relatively slow," he said. "The horned dinosaurs and the duckbill dinosaurs which were its staple diet were no kind of sprinters.

"This rules out fast bursts to catch prey, but it could have been a more active but slow-motion predation; large animals chasing each other at relatively low speeds, long duels over extended periods of time."

Alternatively, it could have been a scavenger, although Sellers points out that a fossil hadrosaur has been found with wounds in its spine, probably caused by a T. rex bite, that had partially healed. "It was definitely a living animal that T. rex bit but didn’t kill," he said. "So we know it wasn't only a scavenger."

It's also worth noting, he said, that younger tyrannosaurs, and their smaller relatives, may have lived very differently. "It's possible that smaller theropods like Allosaurus were much faster; they were only 1 or 2 tons," he said. "And T. rex wasn't born big. They grow from eggs, so you could have had a changeover from quite fast-moving juveniles to big, slower-moving adults." That would mean that adults wouldn't be in direct competition with their own young – "baby T. rex wouldn't chase a great big hadrosaur, it'd be far too dangerous".

The fundamental takeaway from the research, though, is that the image of a fully grown Tyrannosaurus rex keeping up with a fast-moving jeep and trying to bite Jeff Goldblum, as in the movie Jurassic Park, is no longer plausible. "If Goldblum was on a golf buggy or a milk float, it might have had a chance," Barrett said.

CORRECTION

T. rex was among the largest land predators ever to have lived, but probably not the actual largest. A previous version of this story misstated this fact.