How to Train Your Dragon 2

According to a report by The Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative (MDSC), only 2.4% of all speaking or named characters in film were shown to have a disability in 2015 . What’s available to this particular audience and ensuring that there are positive stereotypes portrayed in television and film is important because the socialization process at a young age is quite important. Previous studies have found that people who viewed positive portrayals of disabled people on television programs and in movies were more likely to perceive discrimination towards disabled people and less likely to say they had negative emotions when encountering people with disabilities (Farnell & Smith, 1999). This shows that what people see in the media does play a role in their perceptions. If the portrayals are positive, it elicits a more positive response towards disabled people from non-disabled people. Rather than allow such negative stereotypes about disabled people to persist, which in turn may cause children living with disability to suffer repercussions to their own self-image/self-esteem, it is important to promote high self-esteem by having positive representations of disability in media. Often with popular movie franchises or television shows, they portray characters who have a mental or physical disability as a “supercrip”, their disabilities are glorified as superpowers or as some sort of villain who needs to be dealt with and sent away. Contrary to these stereotypes, the following characters seem to provide positive portrayals of people with disabilities, and hopefully future television shows and films follow suit.

For a film like How to Train Your Dragon 2, which is growing into a large, lucrative and popular franchise, it has the complete attention of a young audience who are still quite vulnerable, and attitudes as well as sense of self and how they will perceive others are prone to change and impact their development into adulthood. To emphasize the importance of representation and how writers portray disabled characters in media targeting children, “Over time, children who watch these portrayals of disability may come to accept the “villainous” or “pitiable” stereotype of disability as normal, which may influence their treatment of disabled people in the real world. Similarly, disabled children who watch these stereotyped portrayals may internalize them, which may have repercussions on their self-esteem and sense of self-worth” (Miller: 9). How to Train Your Dragon 2 does a great job in combating the negative stereotypes and does not try to normalize Hiccup's disability. Hiccup develops a physical disability at the end of the first moving, losing the lower half of his leg when his dragon Toothless saved him from a fire. Gobber, disabled war veteran who equips the villagers with weapons to fight against dragons/enemies, makes Hiccup a custom prosthetic leg. The prosthetic leg is not only used to help him walk around, but it is like a gadget to use while fighting. Hiccup can still run, jump, fly dragons and fight in battle despite his physical condition. The disability is not something that is ignored in the film nor is it seen an injury that causes other characters to interact with him differently. The film's plot does not rely on Hiccups' disability and the overall character development is not affected. The notion of a “supercrip” that one should overcome his or her disability in order to become more normal, is not something the writers tried to do. Hiccup is able to adapt to his injury and continue on with his life; it's not portrayed as some sort of hindrance or challenge that needs to be overcome. In fact, it seems as though the village he lives in embraces this idea that one's disability should not be looked upon as a stopping point in one's life. Instead, whenever someone suffers a physical disability, Gobber is there to patch them up and give them a new instrument (prosthetic limb). This notion of "Here's a problem, let's solve it" is consistent and then everything goes back to normal for that person. Their life is at a standstill for a few minutes as they come to terms with their condition but it is not a long term barrier which would stop them from being a productive member of the community.

There are a few references to his missing leg but conversations about it are not awkward, a few of the characters even make harmless, light hearted jokes about Hiccup's disability. Many characters throughout the film (who are not important to the plot) are disabled themselves but it is not central to the story nor are they negatively portrayed. This lack of emphasis on a main character's disability as well as the acknowledgment of the painful experience he went through when initially injured does not reinforce any stereotypes that might be detrimental to a child's perception of disabled people as they grow older.

Finding Nemo & Finding Dory

Common stereotypes in media portrayals of people with disabilities are that they are victims, they are able to miraculously overcome their disability or succeed despite their disability (supercrip), they lash out at society because of their condition, or they are seen as burdens. As seen in the above video, Marlin, Nemo's father, treats Nemo differently due to Nemo's underdeveloped fin, following the narrative that Nemo is a victim, and as such cannot complete tasks that would be expected of Nemo had he a fully developed fin. Marlin sees Nemo's disability as a vulnerability and thus underestimates his abilities. From Nemo's perspective, he expresses pride in what he calls his "lucky fin" and doesn't feel as though he can't do things that the other aquatic life around him can. Eventually throughout the film, Marlin understands that Nemo's fin doesn’t make Nemo any less capable of completing everyday tasks. An article published in Disabilities Studies Quarterly, Finding Nemo is described as "paint[ing] disability as a flavorful ingredient in cultural diversity – both remarkable, yet necessarily everyday, perhaps even disguised in the tides of life." Nemo is not the only character in the film with a disability (there's a squid with a lazy tentacle and a fish with a physical deformity) and the film seamlessly incorporates varying levels of disability into the story without perpetuating previous stereotypes of disability seen in media. Nemo is not seen as "overcoming" some obstacle despite his disability, and he is also not ostracized because of his fin. The film incorporates an array of characters and treats disability as a marker of the diversity of their population.

Also common within media, disabled characters may not have a central role within the plot or they might be used as a plot device to help the main character complete their journey in the story arc. Dory, a blue tang fish with short-term memory loss, does not follow these stereotypes and is actually a very dynamic and central character within both films. Dory is able to read the writing on the strap of the goggles and help Marlin determine where to find Nemo, making her an essential character to the plot. In Finding Dory, there is still much diversity within the aquatic life of this world. Dory meets a whale shark who has limited vision and often bumps into things, a beluga whale with a head injury that interferes with his echolocation abilities, and an octopus who has lost a tentacle and fears losing another. Similar to Finding Nemo, Finding Dory includes many characters with varying levels of ability, who all seem to come together to create a wonderfully diverse world.

Overall Finding Nemo and Finding Dory both present representations of disability that do not seem to reproduce previous stereotypes of disability in the media. Dory and Nemo are active, dynamic characters within their respective storylines and work with their disability instead of overcoming it as previous stereotypes would suggest. These representations can affect people's socialization to disability and thus are essential for providing characters outside of the stereotypical depictions of people with disabilities.

Avatar: The Last Airbender

In creating the background storyline in which her parents view her as helpless, the creators of the show depict - and challenge - the common ableist narrative which understands people with disabilities to be unable and helpless. Despite her parents belief that they need to protect her from the world, Toph secretly becomes the “Blind Bandit”, winning battles in earthbending tournaments against opponents many times her size. Here, she simultaneously fights a battle against stereotypes of disability.

Toph goes on not only to be autonomous and independent, but also becomes an educator and helps others in crucial ways.

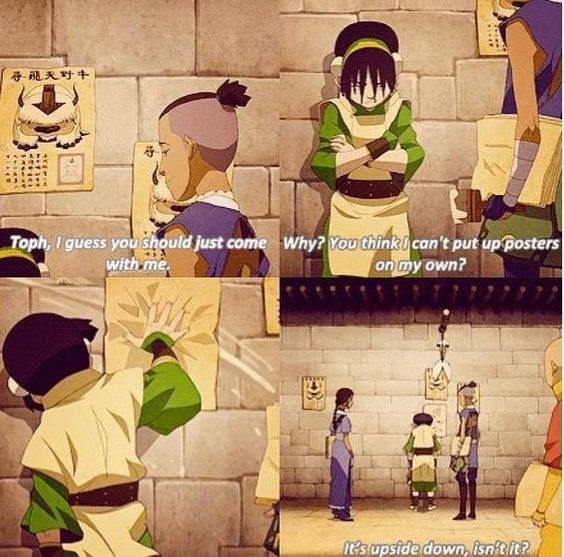

Toph’s character avoids being depicted as a "supercrip". Toph is regularly shown to experience her blindness - it isn’t something that is nullified by her bending, nor is her bending portrayed as something that allows her to be ‘more normal’. They make a point in the show of reminding the viewer of Toph’s blindness in a way that retains that aspect of her life and shows the ways that her disability is not made irrelevant just because she is also a powerful earthbender.

These scenes also show how non-disabled characters succeed and fail to understand and respect her disability. They serve as realistic educational examples of what it is like being a thoughtful friend to someone with a disability, and help to set a precedent for viewers of the show with disabilities the respect and care that they should expect to receive from their friends regarding their disability.

One major limitation of the representation of people with disabilities in Avatar: The Last Airbender is the lack of interaction between people with disabilities, which can be generalized to say that there are a very limited number of characters portrayed as having disabilities in the series. One concept that is useful to consider here is the Bechdel Test reformulated for Disabled People, which serves as a useful tool for approaching the representation of disability. The criteria for this version of the Bechdel Test are, at its most basic, that there exists a realistic depiction of at least one disabled character whose plot developments are not centered around their disability. Within these terms, Avatar: The Last Airbender would pass. However, I think that a Bechdel Test for Disability could go further, and look towards the existence and representation of more than one character with disability. While Toph is a very empowering representation, she is accompanied by very few other characters with disability within her two seasons on the show. For example, the one other notable character with a physical disability, Teo, who uses a wheelchair, is not even on the show at the same time as Toph. The one other central character that is shown to have a disability is a villainous enemy with mental illness (Azula). Because this is not a positive portrayal of mental illness, any interactions that this Azula has with Toph do not help to foster greater representation of people with disabilities. There are no notable interactions between characters with disabilities on Avatar: The Last Airbender.

It is important to show people with disabilities interacting because by not doing so, it removes any trace of disability community. This is significant, considering that according to the U.S. Census Bureau, "Nearly 1 in 5 People Have a Disability in the U.S." Acknowledging the existence of a disability community is an important part of understanding disability as an identity, and as more than just an individualized, isolated experience. Disability is not a singular experience; there is great diversity within the disability community. Depicting only individuals in isolation from other characters with disability erases this reality entirely. Research on children's understanding of mental handicaps and physical disabilities found that children did not differentiate amongst the labels "mentally handicapped", "physically handicapped", or "divvy" (a colloquial term), but only between "normal/abnormal" (Abrams, Jackson, St Claire, 1990). Their study's findings suggest that children who are non-disabled experience a great amount of social distance from their peers who do have disabilities, and are mainly socialized to see people with disabilities as an 'other'. Learning to distinguish between different experiences of disability, not just distinguishing if someone has a disability or not, is a necessary step towards humanizing the experience of disability. Depicting characters with disability amongst one another can help to lessen the 'othering' of people with disabilities.

Conclusion

In our analyses of these characters, we have noted some essential components to the creation of positive representations of characters with disabilities. One thing that is present in How to Train Your Dragon 2, Finding Nemo and Finding Dory, and in Avatar: The Last Airbender are characters with disabilities that are central to the plot, and dynamic. Hiccup, Nemo, Dory, and Toph all are essential to the stories that are told, and evolve throughout the movie/series.

Another important component is the characters' avoidance of the "supercrip" narrative. Throughout each movie, the characters are seen dealing with and working with their disability rather than achieving great things "despite" their disability.

Lastly, it is important for there to be more than one individual character with disability. People with disability do not exist in isolation, and it is important that film and television do not depict this to be true. In How to Train Your Dragon 2, Finding Nemo, and Finding Dory, we see that the characters with disability interact with other significant characters who have disabilities as well. This helps to show that disability does not mean just one thing, but that 'disability' is a very generalized term that is representative of a large community of people. It also proves that disability experience is not, and cannot, be fully captured by one character. In Avatar: The Last Airbender, Toph is the only character that is regularly shown as having a disability, and in our own interpretation of the Bechdel Test for Disability, it fails. Overall, though we have found that they may have their limitations, these two movies and television show provide dynamic and interesting representations of characters with disabilities. Hopefully, these characters can help to set a precedent, and influence creators of media - particularly children's media - to increase, expand, and diversify representation of people with disabilities.

Sources

Thumbnail image from http://www.axia-group.com/disabilities-in-childrens-television/

"University of Michigan Health System." Television (TV) and Children: Your Child: University of Michigan Health System. N.p., n.d. Web. 08 Dec. 2016. http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/topics/tv.htm.

How to Train Your Dragon:

Farnell, O. & Smith, K. A. (1999). Reactions to people with disabilities: Personal contact versus viewing of specific media portrayals. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 76(4), 659-672.

Httyd-Hiccup Lost His Leg. Perf. Jay Baruche. YouTube. IAmHakimi, 3 Dec. 2014. Web. 2 Dec. 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H7muODd2pCo.

Miller, Amy Sue Marie, "Portrayals of mental illness and physical disability in 21st century children's animation." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 40. Retrieved from http://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors/40

Riders of Berk: Hiccup's Leg. Perf. Jay Baruchel. YouTube. NightFuryLover31, 19 Apr. 2013. Web. 2 Dec. 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ad6N_sb0YHQ.

Smith, Stacy L., Marc Choueiti, and Katherine Pieper. "Inequality in 800 Popular Films: Examining Portrayals of Gender, Race/Ethnicity, LGBT, and Disability from 2007-2015." Annenberg.usc.edu. USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, 6 Sept. 2016. Web. 8 Dec. 2016.

Finding Nemo and Finding Dory:

[bhershey78]. (2010, July 20). NEMO_Swimming Out to Sea.dv. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9RhX3lRJQMg

Millett, A. (2004). "Other" fish in the sea: "Finding Nemo" as an epic representation of disability. Disability Studies Quarterly, 24(1).

Rosenberg, A. (2016, June 17). 'Finding Dory' and 'Finding Nemo' change the way we see disability. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/act-four/wp/2016/06/17/finding-dory-and-finding-nemo-change-the-way-we-see-disability/?utm_term=.be0f96873578

Avatar: The Last Airbender:

Abrams, Dominic; Jackson, Debra; St Claire, Lindsay. "Social Identity and the Handicapping Functions of Stereotypes: Children's Understanding of Mental and Physical Handicap." Human Relations, Vol. 43, No. 11, Nov 1, 1990, p.1085

Grimoire, Stacy Whitmans. "Toph: “Supercrip” Stereotype or Well-rounded Disabled Character?" Stacy Whitmans Grimoire RSS. N.p., 4 Sept. 2010. Web. 07 Dec. 2016. http://www.stacylwhitman.com/2010/09/04/toph-supercrip-stereotype-or-well-rounded-disabled-character/.

Hamilton, Anna. "The Transcontinental Disability Choir: Disability Archetypes: Supercrip" Bitch Media. N.p., 18 Dec. 2009. Web. 07 Dec. 2016. https://bitchmedia.org/post/the-transcontinental-disability-choir-disability-archetypes-supercrip.

Johnson, Kjerstin. "Pop Pedestal: Toph Bei Fong | Bitch Media." Bitch Media. N.p., 8 Dec. 2011. Web. 07 Dec. 2016. https://bitchmedia.org/post/pop-pedestal-toph-bei-fong-avatar-feminism-animated-characters.

Konietzko, Bryan, and Michale Dante DiMartino. Avatar: The Last Airbender. Nickelodeon. 2005. Television.

Pate, Emily. "Let’s Make a Bechdel Test for People with Disabilities." Rooted In Rights. N.p., 4 Sept. 2015. Web. 7 Dec. 2016.

[Porluciernagas]. "In Brightest Day: Disability in the Avatar Universe." Lady Geek Girl and Friends. N.p., 20 Sept. 2015. Web. 07 Dec. 2016. https://ladygeekgirl.wordpress.com/2015/09/18/in-brightest-day-disability-in-the-avatar-universe/.

US Census Bureau Public Information Office. "Nearly 1 in 5 People Have a Disability in the U.S., Census Bureau Reports." US Census Bureau Public Information Office. N.p., 25 July 2012. Web. 08 Dec. 2016. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/miscellaneous/cb12-134.html.