It’s the stuff of fairytales: a teenage girl living in what she thinks of as the middle of nowhere goes to a city for the day. She is long-limbed and awkward, out of place among her friends; they are boisterous and noisy and filled with assurance that the world is theirs for the taking, even if it’s half-performance. But that day, she’s the one who gets approached, who is noticed. The question is asked, a card proffered. “Have you ever considered being a model?”

Her friends are envious. She is secretly thrilled. When she gets home that evening, her parents are pragmatic. But it’s all legitimate. She’s been scouted by one of the largest model agencies in London, and they want to see her again. A month or so later she’s on the train with her mum, listening to Emmy the Great on her pink iPod Nano and watching the flicker of shipping containers, abandoned buildings, fields, people’s back gardens. She’s 13, but feels impossibly grown-up.

In London they go straight to the offices, a small wonderland of mirrored corridors and row upon row of beautiful faces staring out from the cards on the walls. In a while, she’s told, she could be among them. The agent she’s there to meet rattles off a list of brands the girl knows from the pages of Vogue: Burberry, Prada, Chanel. Maybe, eventually, she’ll be seen by them too. Shortly afterwards, she signs with this agency. Now, suddenly, she is a model. The word gives her a new currency at school, one understandably laced with envy.

This girl was, of course, me. The story is mine. And the fairy tale is one we've all heard before: the one where a girl gets plucked from obscurity, and is immediately elevated into a much more glamorous existence. Heady stuff, isn’t it? All those new possibilities conjured up, the doors blown open to a whole new future...

But the rest of that (relative) rags to (some kind of) riches story didn’t end up happening for me. It's not what happens for a lot of people in my position, actually: snapped up young, with the hope of a few years of test shoots and editorial jobs before hitting the golden gate of 16, when catwalk work can legally begin. For a few who arrive there, it’s a brilliant leap. Others hit that point with a myriad of pressures to contend with, the main one being a suddenly heightened expectation to lose weight, or at least rigidly maintain a figure unattainable for most. But I, like lots of other girls in turn, bowed out before that point.

I did this mainly because all my preconceived expectations of what the future should look like were shattered when I was diagnosed with scoliosis (a severe curvature of the spine) in my mid-teens and had to undergo intensive surgery to rectify my newly hunched back. In a bewilderingly short space of time I bounced from "ideal" to "anomaly" and on to something else again. But also, two years into the industry, I was already feeling disenchanted. I’d begun to realise that maybe the version of modelling I'd envisaged just wasn’t going to happen for me. And even if it could, I didn’t know if I wanted it. So, age 15, I left my agency with £27 earned (the rest deducted in various expenses – a practice that’s since been cracked down on), a handful of good stories and memories of shoots, and a lingering sense of unease that would take me a long while to work out.

At first I was confused. What did I have to be unsettled by? Nothing especially awful happened. I escaped with my health intact. The appalling experiences that many others have encountered and bravely spoken about weren’t ones I ever came face-to-face with. What a non-story, really: a brief immersion in something that didn’t work out quite how I wanted it to. But, more than half a decade on, I’m still negotiating the consequences of that strange brief period of my life.

Here’s the thing. On the one hand, as a teenager, modelling did throw opportunities and possibilities my way that I couldn’t have experienced elsewhere. I’m still grateful for that. I got to dress up and be taken seriously, and had my first taste of the delicious potential to be found in assuming any number of characters in front of the lens. That meant a lot. Once I even got sent to Paris. That was the highlight: the moment when the job most closely aligned with what I’d expected this shiny new modelling life to look like.

But on the other, I was plunged into a world where I was celebrated for the way I looked. That’s a very potent thing at any age, let alone in adolescence when you’re awhirl with hormones and homework and difficult social situations. And this particular form of celebration – a very short-lived one at that – had its downsides. When I was first signed up, I was 13 and only just on the cusp of puberty. Though still ill-at-ease in my own body, I’d regularly be complimented by adults on my ability to fit the tiniest of clothes sizes. Almost without thinking, I added this into the ways I defined myself: I was slender. This was approved of. When I later finished puberty (which, I’d like to point out, doesn’t begin and end with periods: It’s a process that takes several years) and grew out of the skinny, skinny jeans I’d worn in the Polaroid pictures snapped at my agency, I suddenly felt like a failure. Gaining flesh meant losing something that, this industry had implied, was valuable. Basically, I’d committed the sin of growing up.

It feels silly to admit to much of this now: to describe how subsequently I hated looking in changing room mirrors and regularly cried when I couldn’t fit into clothes my 14-year-old frame had easily accommodated, to admit how it’s only been in the last year or two that I stopped secretly nurturing the belief that one day, eventually, I’d return to my previously limited proportions – or something close to them. Is it silly? Yes. Of course it is. Is it also an honest reflection of the incredibly skewed way we define women’s value, and looks? Absolutely.

I returned to modelling a few years after I left it behind, and continue to dip in and out of the industry. After all, there are still parts of that world that I really, truly love, ones I’m glad I get the chance to engage with in a much more active way (not least the chance to prance around wearing beautiful things). But ultimately I remain ambivalent. More than ambivalent. Unnerved. See, this isn’t just about personal grievances over the nebulous dissatisfaction the fashion industry threw my way as a weird growing-up gift. Rather it’s about how now, at the ripe young age of 22, I’m ever more astonished (and demoralised) by the fact that it was easier for me to sell clothes to adult women back when I was a gawky teenager. Easier than it is now. When I was adolescent and malleable and unsure of myself and everything around me, I embodied an ideal: one that wasn’t strong or well-defined but, quite literally, formless. That was marketable. It sold things. And much as I might have enjoyed the odd day in makeup or striding around in heels, I remained a girl made to look like a sophisticated facsimile of an adult. This form of make-believe was a game for me back then. It took growing up a bit to realise that the game was played on terms I didn’t quite understand.

All of this really hit home a little while ago, when I ended up on a shoot with a stylist who I’d last worked with in my mid-teens. I like her. She’s good at what she does, and I’m still grateful for her support and interest when I was much younger. But on this shoot, one where I’d turned up as an adult woman, complete with hips, boobs, and a much more assured sense of self, she didn’t know what to do with me. My figure seemed to perplex her. She thrust clothes at me that didn’t fit, or were hopelessly unflattering. I was bemused by the whole experience; the way in which a little more flesh could prove so flummoxing. My body – a body I now love and understand more than I did when I’d previously worked with that stylist – wasn’t interesting to her any more. Instead, it was problematic.

I should point out here that I’m 5’11” and a current UK size 10-12. This hovers somewhere between the two acceptable fashion industry types: "regular model" (a UK size 6-8, or smaller) and "plus" (a UK size 14+). Thus I am acutely aware that I’m writing from a position of privilege, given that by most measures this is considered slender: curvier than my adolescent self, but still within society’s "acceptable" – read ludicrous – metric of what’s considered attractive. (Of course it goes without saying that this metric is bollocks, as is the fact that we even have categories like "standard" and "plus".) But when it comes to the fashion world, it’s worth noting that there’s no name for that middle bit, no easy slot to fit unless you’ve carved out a very specific space for yourself.

I feel fortunate that this particular experience happened when I’d already trained myself out of apologising for not fitting teeny-tiny sample sizes. Before that – back when I still judged my worth by my waistline and felt ever so lacking – it would have felt a whole lot worse. Now it’s just frustrating, not only for me, but for the vast numbers of women being done a disservice by the limited imagery that surrounds us. That’s where I’ve come to realise most of my unease is located. We deserve so much more: better representation of body shapes, of skin colours, of ages. We deserve not to feel shit because everywhere we look the prevailing image of beauty remains so far removed from most people’s physical reality.

“Oh, but it’s fantasy!” tends to be the standard line of defence to all this. “It’s not meant to be realistic! This is the stuff of visions, beauty, untrammelled aspiration! You can’t meddle with that.” I always find this a curious response, mainly because I want to ask, who exactly gets to decide what fantasy looks like? And why is it so rigidly drawn – quite literally a one-size-fits-all equation? What does it have to say about the industry’s lack of imagination that such heady visions nearly always stop at a size 6, all the while remaining overwhelmingly young, tall, and white? That it favours lithe-hipped teenagers above fully grown women, even though the latter are the ones who can actually afford the clothes?

Most importantly, what special kind of arrogance does it take to use "fantasy" as the vehicle to sell us the looks, lifestyle, body shape, and wardrobe we’re told we should want to emulate – or at least envy – in our real, actual lives, and then flourish this ruse like a magician pulling back the curtain? “Gotcha! This was entirely out of your reach all along! You weren’t actually silly enough to take any of this seriously, were you?”

There are a handful of other defences too. These go from “well, clothes just hang better on slender frames” (surprise surprise: That’s primarily because they’re cut on and for slender frames) to “there has to be a standard – you need a sample size!”. Samples are the clothes sent down the catwalk and loaned out on shoots. Given that they’re produced in limited quantity, the argument goes, there has to be a singular body shape to make life easier for designers, photographers, stylists, and everyone else involved. Having a model guaranteed to fit the clothes is a necessity, apparently. Nowhere within that argument, however, is there any explanation of just why the sample size is so small: currently needing measurements of around 34-24-34 or smaller (on models, combined with a height of 5’9” or above). I’ve spoken to plenty of models who’ve talked about how exhaustingly, infuriatingly toxic these requirements are – but they have no choice if they want to continue getting work.

It goes without saying that plenty of models are both naturally slender (and/or incredibly fit) and very, very beautiful. Not all of them are adolescent either. Many are in their twenties. And a few (like the remarkable Erin O’Connor) spin out careers over several decades. Others, like Daphne Selfe, are still going in their eighties. It’s all too easy when writing about the fashion industry to lapse into absolutes, ignoring all examples to the contrary.

It’s also easy to engage in body-shaming of one variety or another. In fact, especially when tackling the messy topic of appearance and business (let alone how society/culture/the media at large try to define "attractive"), too many of us accidentally damn one way of being in order to praise another. But this isn't about stressing that any one shape or look is superior. Rather, it’s about examining why it is that our ideals remain so limited, and why much of the industry remains resistant to change.

There are some hopeful signs of shifts, particularly as Instagram becomes an increasingly reputable source for style inspiration, and as traditional fashion models become more accessible and open about their experiences in the industry on social media But it still remains that many of these incredible examples are positioned as exceptions to the norm. Which means there’s still a norm. And it’s a norm that makes a lot of people unhappy.

When these issues surge back up, one could let the upshot be to look down one’s nose, sniff, and dismiss the fashion industry as something venal and frivolous. That response is both reductive and unhelpful though, as well as pretty dull (and possibly tinged with misogyny too, depending on how you go about said dismissal). As with every industry, it has its plus and minus points, its magic and its horrors. What I’m interested in is how we can maximise the former, making the industry more inclusive and thus more exciting.

See, what fashion did offer me, right from the off, was a sense of the playfulness and potential to be found in clothes. It was explosive, giving me a way to define myself, to feel at home in how I moved through the world. I want to see the industry working harder to provide that for everyone: to encourage a sense of thrill in the brilliant qualities of putting on something – a good dress, a perfectly cut pair of trousers, a skirt that swoops with each step – and feeling transformed. But that can only happen if more of us see our body shapes reflected and catered for, rather than being excluded.

That’s what modelling should be about too: a chance to fully inhabit clothes, and the body beneath the clothes. These days I get on with mine. It’s a good body. A practical body. It has stretchmarks, spots, long legs, a slightly wonky torso, and a long, thin scar running the length of my spine. It allows me to walk, swim, climb hills, dance, sleep, have sex, appreciate food, go about my day, and, yes, look fucking great in a green '70s maxi-dress with a dangerously plunging neckline. I appreciate its capabilities so much more than I did as a teenager.

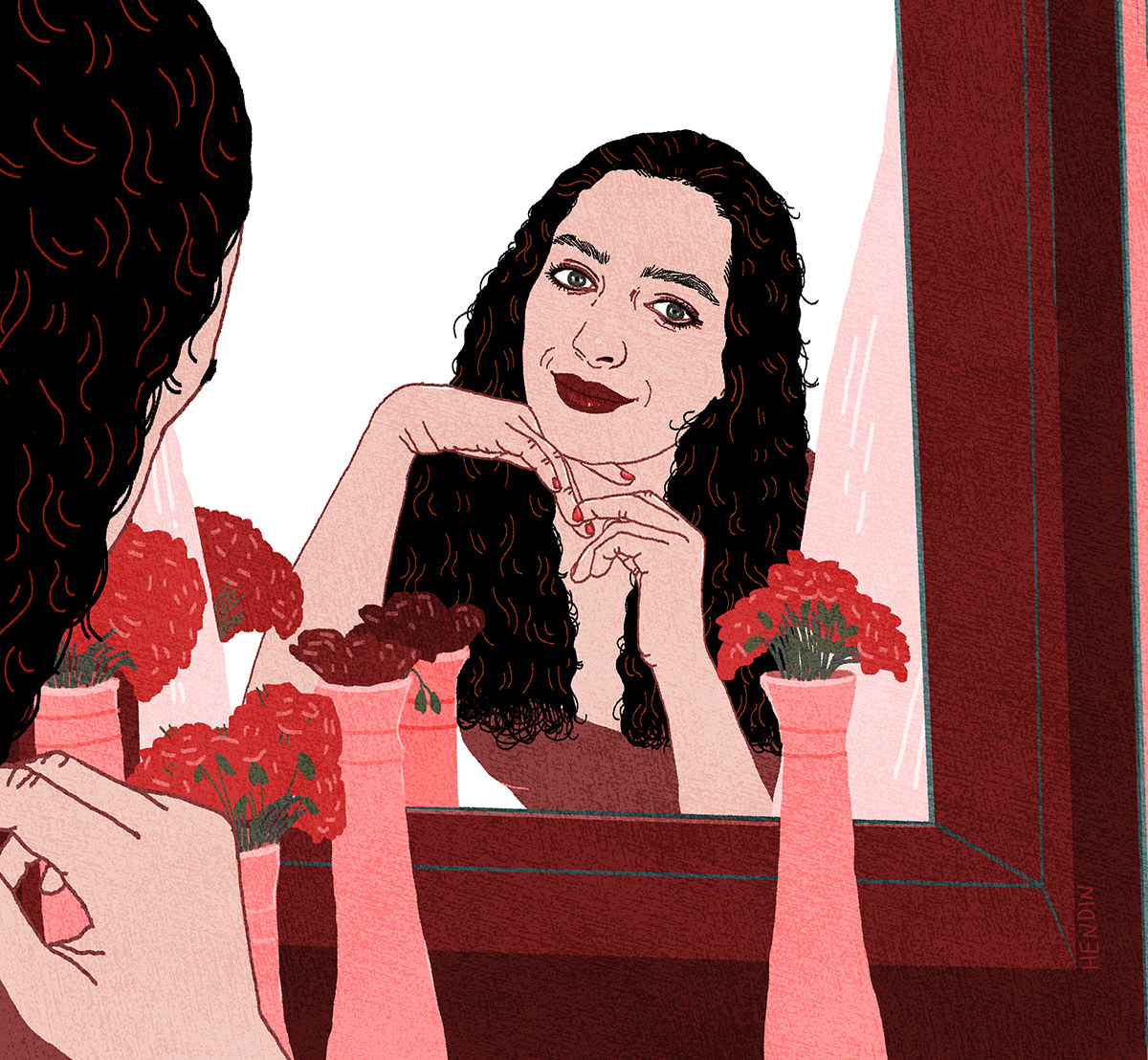

I’m not the first to link modelling to the world of fairy tales. It’s a well-worn analogy, not least because they both tend to have young women as the main protagonists. But perhaps a better point of comparison would be a trope often found within those stories: the mirror. What better to cite when talking about an industry obsessed with who gets to be the fairest of them all? Ultimately, though, (yeah, you can see where I’m going with this), more of us should get to see ourselves mirrored – to know that "fair" doesn’t have a singular face or body shape. Imagine that. What a rich reflection that would be. ●