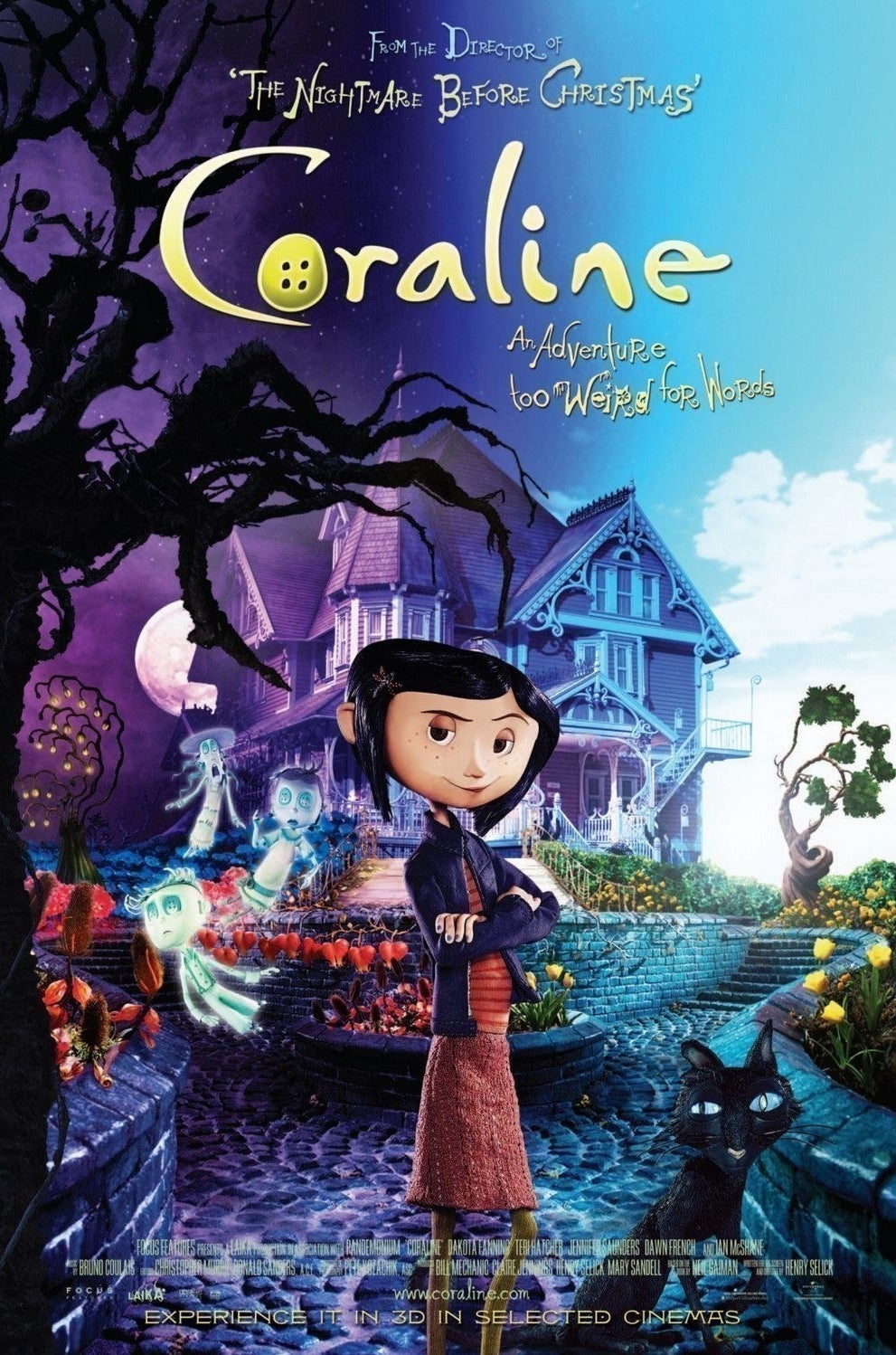

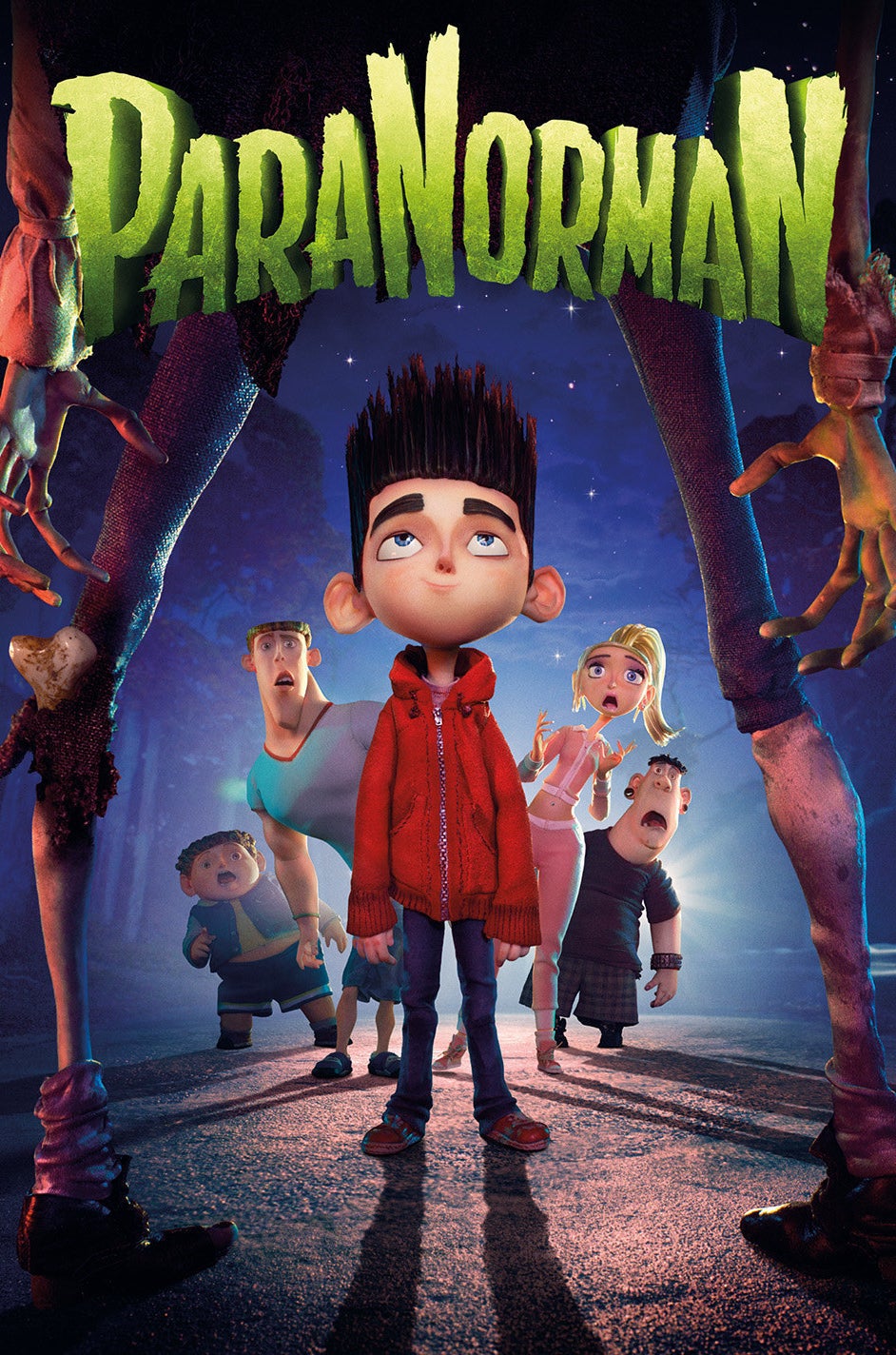

Travis Knight, the CEO of Portland-based animation studio Laika, has worked for two decades in the field of stop-motion animation – in which movie characters are built as real-life, physical puppets and photographed frame-by-frame to appear as if in motion. He served as a lead animator for the studio’s first three feature films, Coraline, ParaNorman, and The Boxtrolls, and took on producing duties for the latter two. All received Best Animated Feature Oscar nominations, and two gained BAFTA wins.

Coraline (2009), ParaNorman (2012), and The Boxtrolls (2014). (Laika Studios / Focus Features)

This month, with the release of Laika’s new film, Kubo and The Two Strings, Knight adds movie director to his impressive resumé.

Kubo and the Two Strings is a sweeping fantasy set in ancient Japan about a young boy (Kubo, voiced by Game of Thrones’ Art Parkinson) living a quiet existence in a small village with his mother until evil spirits from his past track him down. He must then go on an epic journey to defeat them. The voice cast includes Matthew McConaughey, Charlize Theron, Rooney Mara, Ralph Fiennes, Brenda Vaccaro, and George Takei, and the story is at once funny and sad, dark and beautiful, heartwarming, colourful, and immensely gripping both emotionally and visually. It’s that rare thing: a film equally suited to the young and the old.

View this video on YouTube

Kubo and the Two Strings: Official Trailer

Kubo combines traditional stop-motion – one of the oldest forms of visual effects in cinema, seen as early as 1898 – with CG-enhanced backgrounds and effects in ways never before attempted. To make it, Laika pioneered new technologies that even now are hardly available outside of the studio and its partners’ capabilities.

Stop-motion animators at work, circa 1955. (Evans / Three Lions / Getty Images)

The studio's advancements include super-detailed multicoloured 3D plastic printing, used in combination with rapid-prototyping to create versions of the characters’ faces that animators swap out by hand to create frame-by-frame expression changes. This technology was developed and used for the first time in the world in 2009's Coraline, and Laika has been pushing its limits further with each film – it won a technical Oscar this year for its advancements and contribution to character animation and the stop-motion industry at large.

These new methods have allowed for more character facial-expressive range in Kubo than has ever before been seen in stop-motion, with 66,000 unique faces produced for the film. (For comparison, the title character in Coraline had 6,333 faces printed to allow for 207,000 possible facial expressions. Kubo has 48 million possible expressions.)

Nearly all of Kubo’s main action is filmed using traditional stop-motion – perhaps the single most laborious way to construct a film that there is. Each second of finished footage is made of 24 frames, meaning that for one second of onscreen action, an animator must move an entire scene very slightly 24 times. And that doesn’t take into account that some scenes are composites of multiple overlaid shots. The whole thing is maddeningly time-intensive and requires a huge team of dedicated artists, craftspeople, and technical whizzes to make it all happen.

BuzzFeed had the chance to talk to Knight about stop-motion animation and the making of Kubo. Here’s what he had to say:

What drew you to the Kubo story?

Travis Knight: When I was a kid, I was a huge fan of big, epic fantasies. I absolutely adored C. S. Lewis, L. Frank Baum, Lewis Carroll. When my mom was pregnant with me and after I was born, the book that she was reading was Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. So in a very real way, this love of fantasy has been part of my life since I was a baby. I’ve always wanted for us at Laika to tell a big fantasy story.

Then, when I was around 8 years old, [my dad] let me tag along on one of his business trips to Japan. I grew up in Portland, Oregon, and going to Japan 35 years ago for the first time was like I’d been transported to another world. It was so completely unlike anything I’d ever experienced. The beauty of it was otherworldly and extraordinary. Everything from the architecture and the art, to the movies and the music and the food, the style of dress – everything. The comic books. It was a revelation. And it was the beginning of a lifelong love affair I’ve had with this great and beautiful culture.

So the film is kind of a convergence of those two things. The love of fantasy that I got from my mom, and the love of the transcendent art of Japan that I got from my dad. All bound together in a film that’s about the sustaining love of family. It’s a film that’s inspired by family, and it’s about family.

How do you approach darker thematic elements – such as the acceptance of death – in an animated film? Is it any different to making a film targeted solely at adults?

TK: At Laika, we want to make movies that are thought-provoking and emotionally resonant, that hopefully reach the audience’s life in some way. We’re not interested in making little pop culture confections. That means that if we’re telling a story, we want it to be thematically meaningful and explore meaningful topics. We don’t want to make little trivial bits of ephemera.

For this film, as we started to dive into what the structure of the story could support, we really did land on loss, and grief, and impermanence. Through the stylised prism of fantasy and animation, you can explore these deeper, heavier subjects, in a way that kids can understand – in a way that sometimes can be difficult to talk about, to articulate to a child. But when they see it dramatised onscreen, you take the sting out of it a little bit, because it’s a puppet. It’s not a real person. It actually can make those things easier to understand.

That’s what movies can do; that’s what stories can do. That's what we try to explore in this film – the idea that loss is a fundamental part of life, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t carry the stories and the experiences of the people we love. They can still be a part of our life if they’re not physically here any more.

Kubo has an incredibly strong sense of magical realism. Can you explain the creative process of taking that from concept to drawing board to physical shoot, and how you ensure that magical feeling ultimately reaches the screen?

TK: There is something inherently magical about stop-motion. You have this inert thing, this doll, this assemblage of steel and silicon, that through the will and imagination and skill of the animator can be brought to life. It’s the closest thing to magic I’ve ever seen. It’s amazing to see these things come to life, where you forget that they’re a doll, and you view these things onscreen as living, breathing things with hopes and dreams and aspirations and vulnerabilities.

Magic is a huge part of this story. So we wanted to make sure that we dramatised that in the best way. With Laika, we don’t want a house style. It all comes from the same artistic community, so there are strands of DNA woven throughout all of the films, that unite them together. But aesthetically we want each film to feel and look different.

Because of the themes, because of the setting, because the inspirations for this film, the influence came primarily from classic forms of Japanese art. Origami is a huge influence on the film. Ink wash paintings, Noh theatre, late Edo period dollmaking, which inspired a lot of the designs in the movie, and Ukiyo-e – pictures of the floating world. The most well-known form of that is the classic Japanese woodblock print. In some ways, we wanted the film to look like a moving woodblock print. That ensured that it was going be to aesthetically be a different kind of experience for the audience – something they hadn’t really seen before.

Left: Traditional Japanese Noh performance. Right: Japanese woodblock print by Gillot, circa 1875. (Getty Images)

TK (continued): [The character] Kubo is effectively an animator. He takes these inert objects, these geometric shapes, and through his will and his imagination, he can actually breathe life into them, make them come to life in a different way. He becomes something of a proxy for the animators that work on the movie.

We wanted the film to start with one foot in reality. As we progress in the fantasy, things just become increasingly wondrous and beautiful. Everything gets heightened – the palette, the colours – it just becomes more rich as the character proceeds.

In some ways, that’s a metaphor of what it means to cross that transition, to cross that Rubicon from childhood to adulthood, because there are so many amazing, beautiful things that you see in a different way once you begin that maturation process. But then there’s also loss. There are things that you leave behind. We want to make sure that we explore both aspects of that; that there are a great many things that come from coming out of childhood, but there are some things that you lose. It’s bittersweet, which ultimately I think is what the film is.

What is the day of a stop-motion director like?

TK: I would get there pretty much before anybody would show up at the studio. I’d go out to my set, animate for awhile, and once people start showing up, then the day would begin. On a typical day, you start with your production team, going over everything that needs to happen over the course of the day. You bring the animators in and you look at a sequence, you look at a specific shot, you talk about the emotion of the shot, the basic choreography. Then they go off on to their unit, and they’ll do a rehearsal, where they’ll work through the basics. We review that, and then you’ll launch them on the actual shot.

You bring in your set dressing and your camera teams, where you look at how a set and lighting are coming together on the specific sequences. You go out, you have design reviews, where you figure out what the puppets are going to look like, and how the sculptures and the costuming is coming together. You have visual effects reviews, where you look at how all that stuff is starting to come together out of the VFX department.

You’re just kind of bouncing around all day long from one thing to the next. As a director, you’re at the nexus of every critical artistic, and creative, and technical decision on a show. It can be exhausting, but it’s amazing, because you interact with so many incredible artists: people who are seamstresses, people who work in ceramics, who are making things with their hands, people who are designing puppets. You try to inspire your artists, but your artists are ultimately inspiring you, more than you ever could inspire them. And that makes you want to create a film, to lead a film, that’s worthy of their efforts. They’re so passionate. They love what they do so much. They’re so incredibly talented. And they pour so much of themselves into their work.

The air really does crackle with creativity – the inspiration that you get from all these different departments and the little miracles that people are creating daily. I’ve been doing this for two decades now, and I still feel like a kid in Disneyland every single day.

What are your thoughts on stop-motion versus computer animation?

TK: You can tell a great story, you can make a beautiful film, in basically any medium. We take techniques from the stage, from live-action films, from stop-motion, from hand-drawn animation, and from CG animation, and we converge all those things together. I think that’s one of the things that make them visually so interesting, so different, is that it’s all those things combined.

Stop-motion has its own unique quality and charm that is unlike any other form of filmmaking. It was one of the first visual techniques ever developed for film. It goes back to the dawn of cinema, when Georges Méliès was sending rockets to the moon. He was using a lot of the same techniques that we use to make films to this day.

TK (continued): I think one of the things that makes Laika so unique is how we bring technology into the mix, in a form of filmmaking that’s essentially art and craft at its core. That convergence of things, where you’re having people who are Luddites working side-by-side with technophiles – any time you have people who approach art in a completely different way working side-by-side, you create fertile ground for innovation and creativity, and that’s what happens at our shop.

Why is stop-motion retaining popularity, while 2D animation is less so?

TK: Forms of art stay vital because people champion them. It won't happen on its own. Laika’s been in existence for 10 years, and we’re trying as hard as we can to keep this medium of stop-motion alive, because we love it. We think you can tell beautiful stories within this medium. But, you know, if we weren’t doing it, what, you’d have Aardman? That’d pretty much be it. These things only stay alive because people see that they have benefit and value, and try to keep them alive.

2D animation was the main form of animation for generations. The ascendancy of the computer threatened hand-drawn animation, it threatened stop-motion animation, because anything that we could do, as craftspeople, in our mediums, the computer could do better with greater precision and flexibility. So we had to find ways that we could reinvigorate these mediums that we love, and bring it into a new era. So our approach was, essentially, to embrace the author of our demise – to fuse those things together.

With hand-drawn animation, I don’t think we’ve seen many fervent champions of it as a medium. I still love it. In fact, I would love, in the fullness of time, for us at Laika to do a hand-drawn animated film.

You still see places like Ghibli, which sadly are looking like they’re not going to be doing a whole lot of animation anymore. They’re still flying the flag, keeping it alive. And you see places like Cartoon Saloon in Ireland, who do beautiful things in hand-drawn animation. But all the big studios have moved, and are completely committed to making films in CG, which is great – you can do great stories in that medium. But we shouldn’t discount how you can still tell beautiful stories in these other mediums as well. But it takes someone who believes in it, and is really going to champion it.

Finally, our all-important Big Interview Question at BuzzFeed is usually the hard-hitting, "Do you prefer cats or dogs?" But what I’d like to know is: Do you prefer animating cats or dogs?

TK: I don’t particularly like animating either one of them.

Controversial.

TK: They’re a pain in the ass. Although I will say, I animated these Scottie dogs on Coraline, which I loved because they were so weird. They had a little base, and they were these frantic little wild creatures. I really enjoyed animating them. They were about this big [motions 4–5 inches with his hands]. I also animated a cat on Coraline, and the thing that was tricky about the cat was that with four legs you have to do twice as many drilling into the set as you’re animating the stop-motion. Those legs were so tiny, and didn’t support its weight very well. So, what would I prefer? I guess a cat. I think I’m probably more of a dog person, generally, but I’d probably would rather animate the cat. I think they have more interesting personalities.

That’s a very fair and diplomatic answer.