The government has paid out millions of pounds after wrongly classing asylum-seeking children as adults, BuzzFeed News can reveal.

Legal costs, including compensatory damages and barristers' fees, totalled £4,437,410 as a result of losing 262 court cases over age disputes since 2010–11. The amount spent on each case over the six-year period has nearly doubled to £24,771.

Croydon council, which runs the only Home Office asylum-seeker screening unit in the country, provided the figures under freedom of information laws.

One source with experience of working on hundreds of age assessments claimed councils in the UK are overstating the ages of asylum-seekers in order to cut costs.

The source, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they are involved in sensitive cases, said: “It's complicated and very cruel, it's ignoring best practice and designed to save money. These minors are expendable, I fear. I'm a bit exhausted from the anxiety of seeing the blatant disregard for what are nearly always children.”

Judith Dennis, policy manager at the Refugee Council, told BuzzFeed News: “The human and financial costs of local authorities wrongly judging children to be adults are wholly unacceptable.

“If local authorities want to avoid these penalties then it’s vital they prioritise getting their decisions right the first time around by following good-practice guidance and assessing children’s ages lawfully.”

Stewart MacLachlan, legal and policy officer at Coram Children’s Legal Centre, said: “There's lots of examples of bad practice where age assessment isn't carried out to the required standard to which you'd expect.

“And these disputes are a very adversarial process often involving a vulnerable child, who is often stuck in limbo because an asylum claim may be delayed while the age issue is resolved.”

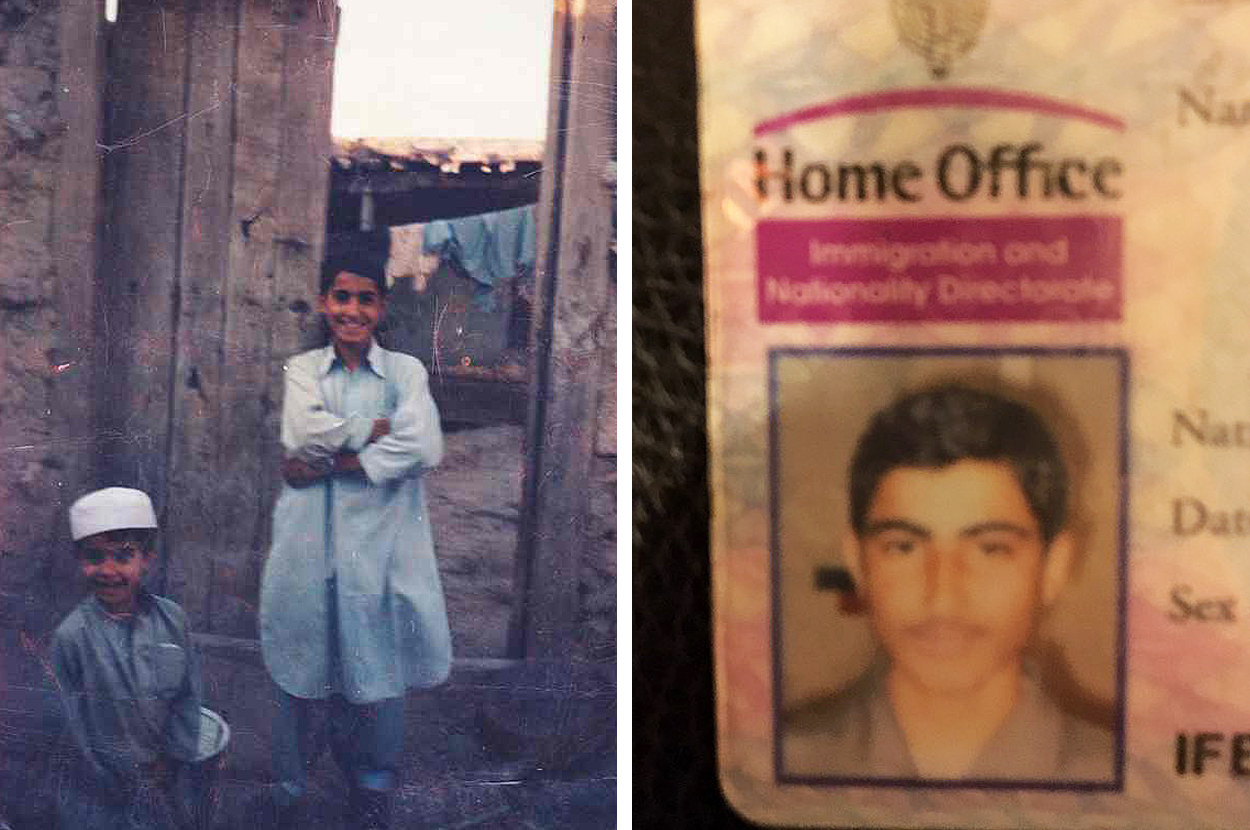

Gulwali Passarlay, who entered the UK aged 13, had his age disputed for almost two years. "I felt worthless and unvalued," he said. "I attempted to commit suicide twice because I thought there was no point to life. I was called a liar, a criminal.”

Passarlay, now 22, said he fled Afghanistan after his father and grandfather were killed, adding: “I went through trauma, I went through hardship. I've seen things at a young age that nobody would ever see in their entire life. My home became a war zone, seeing people dying, seeing houses burn down. I've seen things that have made me age.”

In June, the High Court ruled that the Home Office’s policy of judging the age of unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors based on their appearance was unlawful.

The latest 12 months of data, up to September 2016, suggests there were 3,144 asylum applications in the UK from lone migrant children. Afghanistan (783), Iran (435), and Albania (426) were the sources of most applicants.

Each year, around a quarter of all unaccompanied children claiming asylum in the UK have their ages disputed.

A 2013 report published by Coram Children’s Legal Centre found that the length of time taken to resolve the issue of the child’s age ranged from ten months to over four years. Figures released by the Refugee Council revealed at least 127 minors were held in adult detention between 2010 and 2014.

Alison Harvey, legal director of the Immigration Law Practitioners' Association, said: “Our main concern is that age is disputed as a matter of course, far too often. The grail of date-stamping a child is unattainable: Age assessments are an art, not a science.”

She said in many cases where a payment to an asylum-seeker is agreed, as opposed to a court awarding damages, a gagging order is imposed so that the sum cannot be disclosed. “There is therefore very little information in the public domain about such settlements,” she added.

Dr Bhanu Williams, international officer for the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, called for a “holistic” approach to age assessment.

She said: “I think that there should be a presumption of belief, not disbelief about young people who come in claiming to be under 18. And an acceptance that the hardship they have endured may have aged their appearance.”

"We need to be more compassionate and more kind to asylum-seekers," said Passarlay. "We should investigate ages but do it in a way that is acceptable.”

A spokesperson for the Home Office said: “The Home Office and local authorities have a duty to safeguard children and not to place children in adult services or adults in children’s services.

“We are committed to working with local authorities and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to improve the age assessment process.”