Australian government and intelligence whistleblowers – and potentially even journalists – may face up to 20 years in jail for disclosing classified information, under the most sweeping changes to the country’s secrecy laws since they were introduced.

The Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull has announced a broad package of reforms aimed at curbing foreign interference from countries including China and Russia.

The legislation was introduced by Turnbull in the House of Representatives immediately after marriage equality passed on Thursday evening, and the otherwise full House of Representatives was emptied as celebrations were underway.

While the reforms have been flagged for many months, they were only introduced on the last sitting day of parliament this year, and go much further than previously believed.

Unexpectedly, the reforms include sweeping changes to longstanding secrecy laws, which are modelled on Britain’s Official Secrets Act.

The regime raises fresh concerns for prospective whistleblowers, journalists, and also mass leak publication sites such as WikiLeaks. A series of “aggravating” offences will also hamper large-scale leaks like those from former US National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Currently, a single offence under the Crimes Act prohibits disclosures of almost any information by Commonwealth officers. This has been roundly criticised by news organisations and human rights groups, and the Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) has recommended changes to curb the scope of information captured by the offence. A further “official secrets” offence also potentially criminalises any disclosure, although the threshold for this offence is high and it has been rarely invoked.

Under the proposed new regime, both offences will be repealed entirely and replaced by several new offences inserted into the Commonwealth Criminal Code. While a seven-year jail sentence is the maximum available under the existing laws, this will be radically increased to up to 20 years for the most serious aggravating in the proposed laws.

The new laws will apply to anyone, not just government officials. They could easily apply to journalists and organisations like WikiLeaks that “communicate” or “deal” with information, instead of just government officials. They will also close a longstanding gap around contractors working on behalf of government agencies, who will also be subject to the new offences.

The bill’s explanatory memorandum highlights that it seeks to prevent the publication of almost any information from intelligence agencies, giving the example of salary information of officers.

“Even small amounts of such information could, when taken together with other information, compromise national security, regardless of the apparent sensitivity ... For example, even seemingly innocuous pieces of information, such as the amount of leave available to staff members or their salary, can yield significant counterintelligence dividends to a foreign intelligence service,” it said.

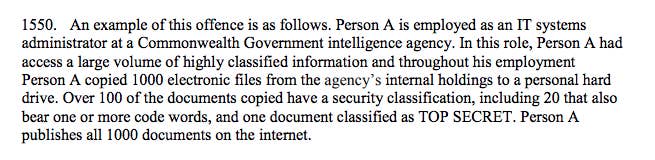

It lists an example of a set of circumstances particularly similar to Snowden for the aggravating offence.

Journalists will have a defence available to them if publication of information is considered to be in the public interest and is “in the person’s capacity as a journalist engaged in fair and accurate reporting”.

However, they bear an evidential burden for proving their conduct satisfies the defence.

No definition of journalist is provided in the bill, and it is unlikely to capture organisations or individuals who play a less traditional role in news gathering, such as WikiLeaks, independent bloggers, or intermediaries who pass information along to journalists but are not the original source.

It places news organisations in the position of potentially having to justify their reporting in court if a prosecution is brought against them.

An aggravated offence will also be introduced that could see a journalist or whistleblower jailed for up to 20 years. Factors for this offence include whether the information is classified as secret, if it is marked with a codeword, or if it involves the dissemination of more than five records with a security classification. That classification could be as low as "protected", a marking used broadly across hundreds of Australian government agencies.

This offence appears to be squarely targeted at curbing organisations like WikiLeaks that publish large caches of documents. It would also capture whistleblowers like former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. While the laws will not apply retrospectively, they are likely to render any future attempts by news organisations to report on highly classified matters increasingly difficult.

At first glance the proposed laws do appear to limit the type of information that could lead to a prosecution of a journalist or a source. Several of the offences are focused on protecting “inherently harmful information”.

The explanatory memorandum of the bill mentions the confusion and uncertainty around the application of the existing offences, and cites approvingly the ALRC’s review into secrecy laws.

But the proposed regime goes substantially further than the ALRC’s recommendations to wind back and simplify the offences.

Conduct defined as “inherently harmful” is extremely expansive; it includes all security-classified information, information that would or could reasonably cause harm to Australia’s interest, and certain information provided to government agencies.

This poses particular problems because of the overclassification of information within Australian government agencies. Agencies such as the Immigration Department routinely classify large amounts of information as “protected” or “confidential”, with no clear basis and limited systems of review.

It could even include, according to the explanatory memorandum, information provided to the Australian Tax Office materials or Australian Securities Investments Commission.

Further offences will also criminalise the communication or dealing with information that “causes harm to Australia’s interests”, which won’t just include information about law enforcement operations but much broader types of information as well. This includes a broad suite of information about civil and criminal law enforcement that goes far beyond just law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

The explanatory memorandum of the bill acknowledges that this part of the new regime “goes beyond the ALRC’s recommendation”.

“The inclusion of the concepts of preventing, detecting, investigating, prosecuting and punishing Commonwealth criminal offences and contraventions of Commonwealth civil penalty provisions is intended to reflect the fact that the effective enforcement of the law and the maintenance of public order require the undertaking of a wide range of activities,” it said.

The definition of harming Australia’s interests is so expansive it could include disclosures that lessen the cooperation of law enforcement, cause “intangible damage” to Commonwealth and state relations, or cause a loss of confidence or trust in the federal government.

Whistleblowers who make disclosures to journalists or other individuals may be able to gain protection under the Public Interest Disclosure scheme. However, that scheme strongly favours internal disclosures and places substantial barriers and risks for people who are considering making external disclosures.

While the new regime purports to replace the offence for Commonwealth officers, it also preserves an almost identical mirror provision. The basis for this offence, according to the explanatory memorandum, is that it will take time to determine whether there is any separate information not covered by the new offences.

This means that the existing broad regime that criminalises disclosures of all criminal information will remain in place, and effectively be enhanced by the proposed offences.

Australia has faced criticism in the past for its hostility towards whistleblowers. The UN's special rapporteur for freedom of expression David Kaye has previously warned that Australians' rights and freedoms are at risk of being “chipped away.”

These secrecy offences have previously been used to target the sources of Australian journalists. Australia’s immigration department has referred journalists’ stories about the immigration detention regime on a number of occasions for investigation by the Australian Federal Police.

The Australian Federal Police has in turn admitted to accessing journalists' phone and email records without a warrant in order to attempt to track down their sources.

Contact Paul Farrell using the Signal secure messaging app on +61 457 262 172.