You’ve likely heard that Filipino food is the hottest up-and-coming Great American Cuisine. You’ve also likely heard that same story for the past three or four years: Filipino restaurants drawing ardent fans of all backgrounds, but ever always at the margins, perpetually on the verge of breaking into the mainstream. Any restaurateur would be happy to just make ends meet in the über-competitive food scene, let alone in those of Los Angeles or New York.

But there’s been a recent wave of Filipino restaurants going above and beyond, making their marks in the culinary industry — from LASA and the Park’s Finest in LA, to Bad Saint in DC, to Maharlika and Jeepney in Manhattan. Their most loyal followers have been spreading the gospel of talangka fried rice and ube tamales since these places have open their doors. Why is it only now that they're getting the widespread recognition they deserve?

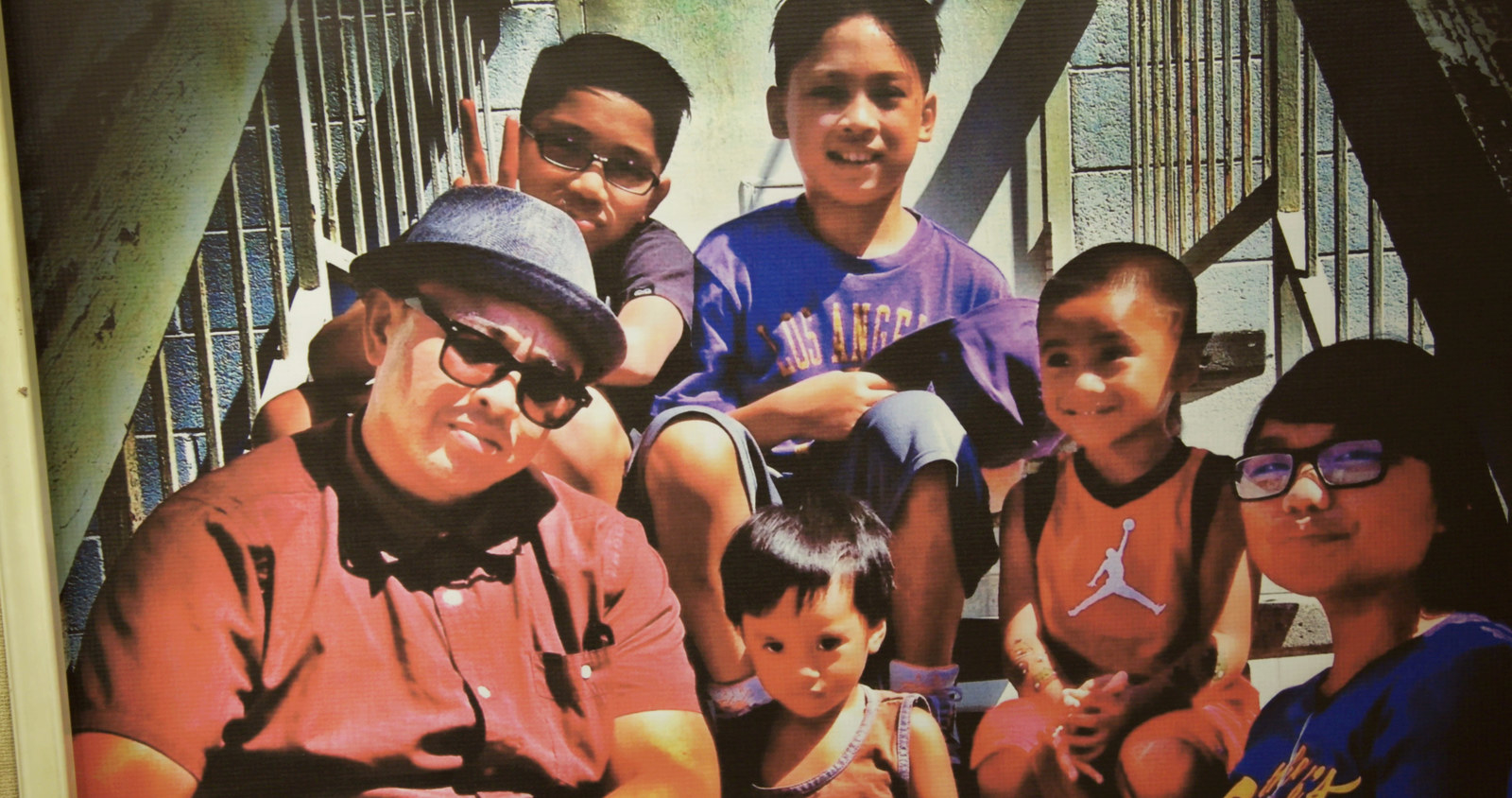

The new documentary ULAM: Main Dish asks just that, positing that today’s Filipino gastro-visionaries are here to stay.

ULAM: Main Dish's director and producer Alexandra Cuerdo (who used to work at BuzzFeed) sat down with BuzzFeed Philippines to talk about the film, how Filipinos use food as a means of communication to share themselves with others, and a new definition for what's considered to be "authentic" Filipino food.

So why do a documentary about Filipino restaurants?

Alexandra Cuerdo: I think a lot about how food is a central part of our culture. I also think about representations of Filipinos in the media. And lately, I've seen plenty of Filipinos coming up in the world of restaurants. Maybe it's weird to say, but I think a chef can be a hero. I think these stories are inspirational and heroic. Speaking to all the chefs in the movie, I learned that the food world and restaurant industry is a difficult world to be in, especially in LA and New York. Restaurants open and close in six months — Filipino restaurants, specifically.

That became a real question: Why don't we see more Filipino restaurants? Growing up, I ate Filipino food almost exclusively at home. When we did go to restaurants, we'd go to West Covina, to the turo-turo places, and we'd have food that reminded us of home. But we'd never take our non-Filipino friends there. We felt we couldn't, because we felt they wouldn't understand it. But where do we have a meeting place for our culture? Where can we gather? Where can we share our culture with non-Filipinos? That's a restaurant.

There’s a lot of that discussion in the documentary, how to present Filipino food in a way that’s appealing to a "Western" palate. How do you think the chefs negotiated that?

AC: It's amazing how different each place was. Every person had a strong vision for their dream Filipino restaurant. The chefs at LASA, for example, they grew up in California and their food is very informed by that: It's chef-driven, with fresh produce, and changes seasonally. Their space also has a relaxed, cool California vibe. But they serve modern Filipino cuisine. It looks so different from what I grew up eating, but that doesn't mean it's not authentic.

“Authenticity” is a word that’s been tossed around when media talks about Filipino food — both by non-Filipinos and Filipinos.

AC: And that's a question that resonated throughout the documentary: What is authentic when it comes to Filipino food?

Nicole Ponseca, who started Maharlika and Jeepney, said in her interviews that she wanted a place where she could take clients when she used to work in advertising. She wanted a place where she could take her company, where they could just pick up the tab and have an amazing night, amazing food, amazing drinks, with servers that could educate non-Filipinos on the intricacies of each dish. That was her vision for her restaurants.

Now, any Filipino-American or Filipino can walk into either of these restaurants — and many have — and say, This doesn't look like the food that I had at home. This doesn't taste like my memories. But that's not the point. Authenticity is personal for each of these restaurants, the ones in ULAM: Main Dish, and for all their chefs. It's specific to their experience cooking and being a restaurateur in America. And it's also specific to the food they grew up with.

The Philippines is an archipelago! It's over 7,000 islands! Across the Philippines, there are many different ways of making adobo. Does that make one recipe more authentic than another? Absolutely not. There's plenty of ways to make Filipino food. In the documentary, I put forward the idea that all those ways are valid. In the same way that there are many Italian restaurants in America, there should be many Filipino restaurants too. Every restaurant should do it their own way, in the way that is most authentic to them.

Do you think Filipino food's entry into the mainstream has been difficult because Filipinos themselves have been so purist about what they expect out of a Filipino restaurant in America?

AC: I think so. I spoke to Johneric Concordia — he's from the Park's Finest, a Filipino barbecue restaurant in LA's Echo Park — and he said something that encapsulates it.

When you grow up eating Filipino food your mom makes, for example, you grow up eating it for breakfast, lunch — you have it every day. You grow up with it and it's part of you. And then you go to a Filipino restaurant and you try their food, and you say, This doesn't taste like my memories. I don't want to pay for that. So you value what your mother made you, that food, those memories. That comes from your family. Now, look objectively at what's in front of you and value where this came from. This came from someone else's family, this came from someone else's mother. It doesn't have to be exactly yours to still be something you can appreciate.

It's a theory I've heard a lot, that Filipinos don't support Filipino restaurants. I don't think that's true on the whole, but I do think there's people that convincing. It may be the older generation; it may be a generational gap. It may be the difference between being born in the Philippines and being born in the US. But I think it's more complex than that.

There's a lot of pressure and significance that we put on food as Filipinos.

AC: It's us. It's like saying, This is me on a plate.

Mia Alvar, the Filipino author of the short story collection In the Country, said in an interview that she initially shied away from including too much food in her stories about Filipinos. Ultimately, she said, she couldn't be disingenuous. For one thing, it's something that brings people together. Food is a key tool for Filipino immigrants.

AC: Using food to care for somebody is a very human trait. I don't think it's unique to immigrants, or even to Filipinos. It's just something that Filipinos in particular have adopted, especially in these restaurants. You go in and you feel part of the family.

Right. Food is how we get to know each other — Oh, this is your recipe for fruit salad? This is my recipe for mango supreme. We kind of trade in that and we form our bonds.

AC: It gives us a connection to fellow Filipinos and Filipino-Americans. We can say, we both enjoy this, this is some version of what we both grew up with, it's some version of ourselves — even more so when we're connecting with a non-Filipino. I can say: This is a version of me, this is a version of my history, what I grew up with, and you should try it. If you don't like it, that's OK. I have twenty other dishes for you to try.

That's the reason why I interviewed so many different kinds of chefs and restaurants. The more Filipino food you have, the more you understand it. And this film is by no means a bible to Filipino food. If anything, it's just an attempt at opening the door and saying, Here are some places you should try. Keep an open mind and see what you think. It's so difficult to explain Filipino food to somebody. You just have to eat it.

How did your experience as a Filipino-American influence your storytelling about Filipino-Americans?

AC: Personally, I grew up in Southern California, in predominantly white neighborhoods, in predominantly white schools. It wasn't until much later in life that I really wanted to explore my roots. Because when I go to the Philippines, I'm seen as American. When I'm in America, I'm seen as Filipino. I felt between two worlds. I think that's an experience a lot of the chefs in the documentary had too.

For example, Charles Olalia from Ricebar — he spent his entire career up until now making top-of-the-line French food. He's worked at places like French Laundry and the Ritz. And for his first restaurant, he wanted to go back to his roots. He was born and raised in the Philippines, but he could have come out the gate and made a French restaurant. It would have been so great. Instead, he pulled together his time, his resources, his energy to do something that felt like home to him.

I think that's really what it comes down to at the end of the day for me too, why I made this documentary. It was me trying to connect with home. In a big way, I think that Filipino food is America. It has been for me. I think it will be for many future generations. If I had an ultimate vision for Filipino food, it's that it would become as woven into the American experience as Filipinos are. •

ULAM: Main Dish premieres at the San Francisco International Film Festival on Saturday, April 7.