The smell of sofrito sizzles from the kitchen and it’s a sign of love. A visit to Abuela’s house always means the best Puerto Rican cooking in the Bronx. It also means being able to gather family stories. I’m 8 years old and I know enough to keep quiet, pay attention when the grown-ups speak, and lean forward to catch all the words they say. Family stories are the only currency of value, the inheritance I will take with me wherever I go, but a picture held in your hand is proof of a life before yours. I watch with anticipation as my aunt drags out the photo albums tucked away in a closet.

I’m too young to hold these images without supervision so I sit as close to her as possible. I want my aunt to know that she can trust me with these tiny treasures from the past. There are many pictures taken from Puerto Rico. Images of my grandfather looking like a gangster in a linen suit and fedora. Wedding pictures with the bride looking glorious in a rental bridal gown. Cousins smiling wide grins full of sunshine and candy. My aunt selects a photo I’ve never seen before and holds it delicately. Its importance is obvious so I calm my excitement down as best I could.

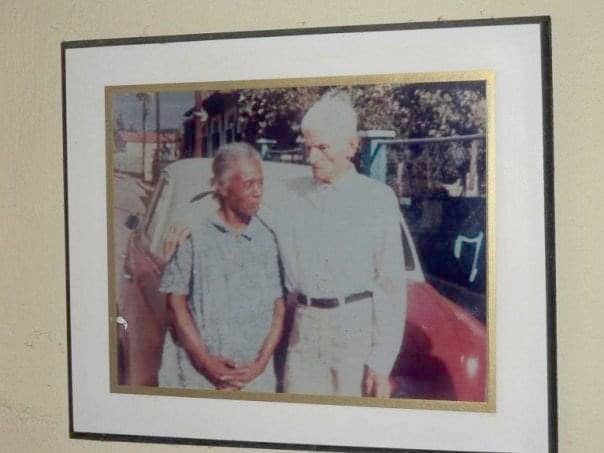

“This is your great grandfather and grandmother,” she says.

The couple is old. Their gray hairs float everywhere. They stand erect next to each other with wrinkly hands neatly tucked beside them. He wears a simple outfit of a striped shirt and slacks but my eyes stay only on her — on my great grandmother. She’s shorter than her husband but that isn’t the only difference. My great grandmother is Black and so many questions come to me. Why has no one spoken about her being Black, of her being Afro Latina? Why is this a secret? My family is a hue of colors. Line us all up and you’ll find trigeños, olive skin, and fair skin with blonde hair and green eyes. We come in all shades. Yet, this is the first time I hold evidence of our African lineage, the clear proof of how the branches of our family tree encompass so much more.

“She’s Black,” I say.

My aunt takes the photo back.

“She’s not Black.” There is a slight edge to her tone. “She’s Puerto Rican.”

A wave of confusion sweeps over me. My aunt closes the photo album and with that ends the discussion before it even began. I’ve been taught to respect my elders. I don’t understand her response but I know enough not to question it. This moment lodges into my body like a small tumor.

It’s been more than 20 years since I left the Bronx and moved to Los Angeles, more than enough time to distance myself from that moment with my aunt and to see that day clearly. As a child, I didn’t have the words or the nerve to point out the wrong but now I do. It’s not as if I suddenly woke up and realized how colorism infects everyone in my family. My education was a gradual one that went beyond just reading (The Afro-Latin@ Reader by Miriam Jiménez Román is a start) and included interrogating my own blind spots. The next step was committing to severing these ingrained racist notions and passing along what I’ve learned to those I love, friends and family included.

Now when I visit home, I yell at my father when he starts using racist words to describe a Black person he sees on TV. He usually goes quiet and refuses to speak to me for a full day or two but he knows enough to hopefully not do it again. It’s an uncomfortable act that goes against how I was raised but I do it. I grew up singing along to rap songs, thinking I can say the n-word (remember when Jennifer Lopez did that in a song? Yeah that.). I got into a discussion about this with a brother and we argued about the power of words. I was taught that only certain Black people were to be trusted. Over texts and phone calls, my sister and I recalled these lessons and shook our heads. Arguments carry over to social media with our own cousins who are Trump supporters. And it doesn’t end. This is a job of forever checking my own privilege, seeing where I fall back on these violent teachings meant only to uphold a white supremacist belief that white people are superior to other races. I have honest discussions with my friends through which they check me and I do better because I must.

Colorism is not a new tale. It is a story as old as when the Spaniards landed in Puerto Rico more than 500 years ago. Colorism is rooted in colonialism and white supremacy. It is perpetuated in the novelas our families watch, in Spanish language news, and in our own dialogue. According to a New York Times article posted in August of this year, “More than three-quarters of Puerto Ricans identified as white on the last census, even though much of the population on the island has roots in Africa.”

Black lives matter. This statement is true. If I shake my family tree, where exactly do we land on that statement? Brown and Black pain is real but so is self-hate. White-passing Latinx, including my family, are convinced if they stand close enough to whites, they’ll be elevated to a better life. It’s the same argument used when we complain about not seeing enough Latinx representation in mediums such as film at the very expense of completely ignoring Black Afro Latinos already in front of the camera. Self-hate has convinced my own blood into thinking we can align ourselves with those in power and that we’ll be excused from a long history of racist policies meant to maintain the status quo.

Adrienne Maree Brown wrote a 2018 essay titled “We Will Not Cancel Us” that I turn to again and again. In it, she writes, “We will not cancel us. But we must earn our place on this earth. We will tell each other we hurt people, and who. We will tell each other why, and who hurt us and how.” The essay is a reminder of the work before me, of the work all of my Latinx brothers need to engage in, to continue to love my family and to lovingly call them out. It’s my duty to have uncomfortable, painful conversations to cut down these false beliefs still ingrained in me.

"It’s my duty to have uncomfortable, painful conversations to cut down these false beliefs still ingrained in me."

Soon after seeing that photo of my great grandmother for the first time, my mother put on the 1959 movie Orfeu Negro for my sister and I to watch. The movie is a retelling of the Greek myth Orpheus and Eurydice set during Carnival in Rio de Janeiro. As I sat on our living room sofa with the plastic covers, I watched in wonder at images of beautiful Black and Brown people. I was immediately transported to my mother’s home of Corozal, Puerto Rico, a place in the mountains. She’s spoken so many times of having to travel to fetch water for her family, just like the women in the movie. The young children dancing and playing on the screen looked like my cousins. I’ve seen these faces before; although we’re not Brazilian but Puerto Rican. When I watched Orfeu Negro, I encountered a rare Afro Latino love story celebrated on the big screen, unhampered by the usual racist stereotypes. Both young and old were shown with love, compassion, jealousy, and humor. A full range of emotions.

It may have taken years for me to connect the images of my great grandmother to that of Orfeu Negro but when I did, her story of survival echoed inside of me. I think of all the things my great grandmother had to overcome to continue this family line, so many obstacles placed before her like the young lovers in the film. My latest young adult novel Never Look Back is a retelling of the same myth set in the Bronx with Afro Latino characters. Never Look Back is my homage to Orfeu Negro and it is also an examination of how our own community refuses to see what is right before their eyes. If I’m writing outside of my own lived experience, then I must do right by the research, question everything, and make sure I bring others into the fold to check my work. This thorough examination plays out on the page and in my life.

A sign of love is not just a home-cooked meal. A sign of love is presenting another way of living to my family that collapses this long history of denial of our own people. I really believe people can change and adapt. Anti-Blackness and colorism are insidious parasites but there is hope if we push through this self-hate.

My aunt is now as old as my great grandmother in that photo. When I visit her, we still lovingly look at photo albums. There’s a saying she loves to use to preface each photo she shows me: “En los tiempos de antes,” which translates to “back in those days.” I can gather her family stories while also pointing out to her the changes we must carry through even when she doesn’t understand, and that too is love.

Lilliam Rivera is an award-winning writer and author of the young adult novels Dealing in Dreams, The Education of Margot Sanchez, and the middle grade novel Goldie Vance: The Hotel Whodunit. Her most recent YA novel, Never Look Back, is out now wherever books are sold.

Learn more about Never Look Back here.