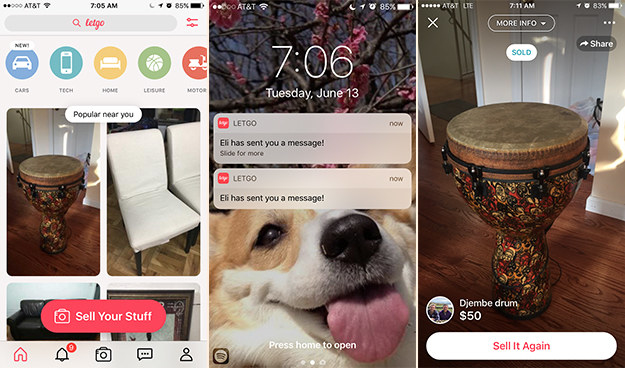

The djembe has sat in the corner of my room collecting dust for four years, and if my grandma knew her gift gets used as a dinner table more than it does as a drum, she wouldn’t be very happy with me.

But what if she video-chats me and asks me to play that dumb drum she loves so much?

This is what I ask myself anytime I think of selling it. After all, I do use it as a drum...sometimes...a few times… OK, during a couple late-night jam sessions in my friend's Williamsburg apartment.

I'm. Never. Going. To. Use. It.

We love our stuff — stuff makes us happy, stuff makes us cool, stuff is awesome! But our fascination with stuff is becoming a problem. As of 2014, the average American home had 300,000 items, and there were more storage facilities than Starbucks and McDonald’s combined.

As a bit of a pack rat myself, I wanted to find out why it’s so hard for us to let go of those items we never use. I spoke with Dr. Jessica Rasmussen, an instructor in psychology at Harvard Medical School and a clinical collaborator to Boston University's Hoarding Research Team.

Why do we love to have so much stuff?

JR: The experience of having and holding onto stuff produces a lot of positive feelings for people…feelings of safety, pride, preparedness, nostalgia, sentimentality, and an emotional piece. Those who have stuff or are holding onto stuff are getting these positive experiences from that, at least in the short term.

For example, I appreciate this beautiful piece of art, so I hold onto it right now in the moment because it makes me feel good, but it may also be associated with positive experiences that I’ve had in the past. It’s not just that possessions or stuff gives us positive experiences in the moment; the same actually holds true for anticipating what something is going to do for us in the future. Which actually is why, probably, consumers are not just holding onto things but also buying things or taking in more items. We have more income to spend — consumerism has increased — but actually that satisfaction has stayed the same, so there is a perception that having items or having more items will make us feel good when, in fact, we know that’s not necessarily the case.

What do you mean? What’s the emotional impact of having a lot of stuff?

JR: One thing I would say is the emotional impact of having too much stuff is that it has a potential to produce more negative emotions. It becomes difficult to do more things easily on a day-to-day basis…finding things that we need, feeling like we have a clear living environment, completing our activities of daily living. If you have too many things, people are less likely to appreciate the things that they have in their immediate environment. Also, what I’m referencing is that we have this impression that this is going to make us feel good, that it will improve our quality of life, when actually there is research that shows that having more stuff, consuming more, does not actually produce long-term quality of life satisfaction for people ... Relationships, spirituality, altruism — these are the things we think about when we think about what’s actually going to make us happy.

So if having a bunch of stuff is not the key to happiness, how do we work on having a life with less stuff?

JR: It’s about setting some time aside to try to take some inventory of what you currently have.

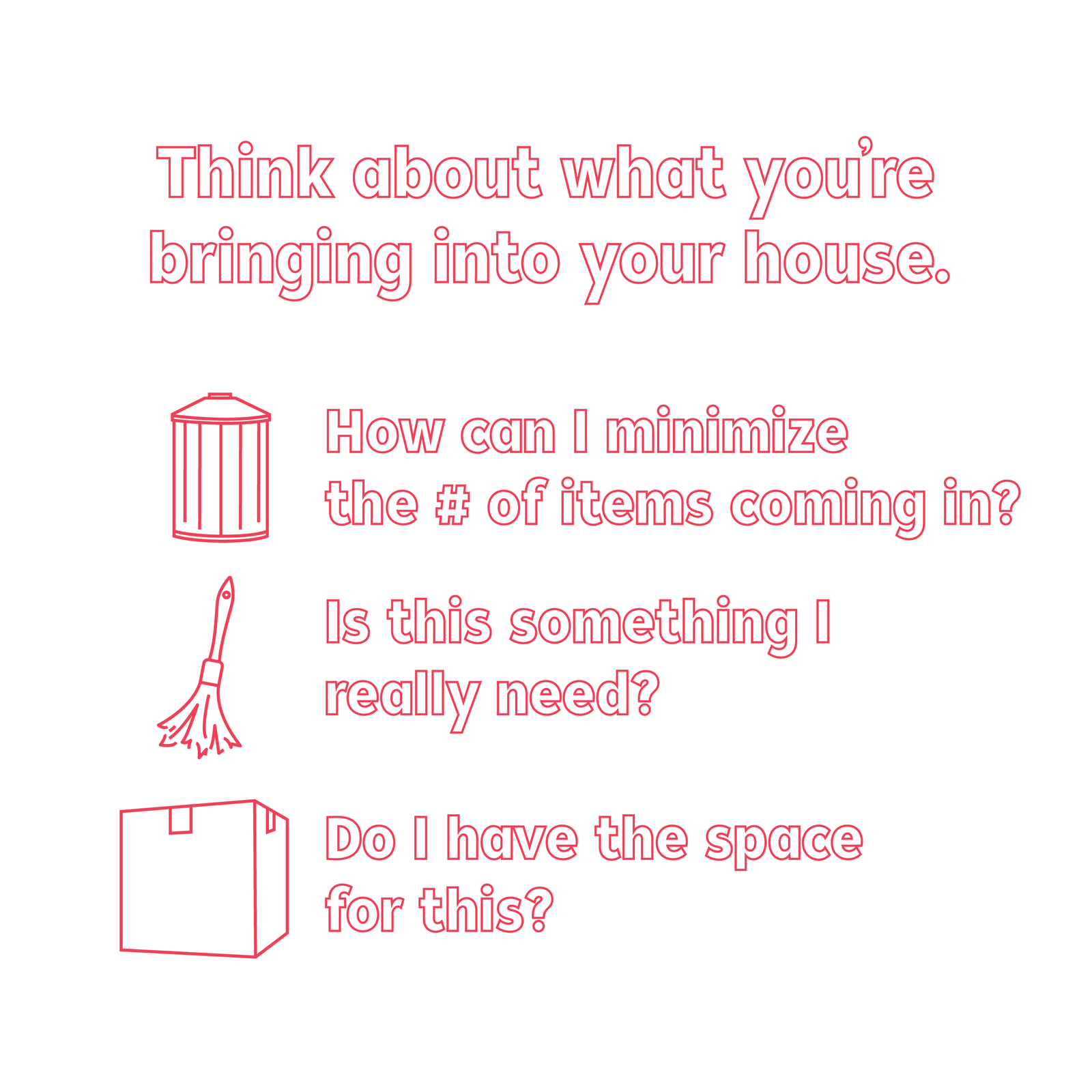

People will describe their stuff all over their table or on their counters, and we think about if that is really a space where we would normally store things. No, not necessarily, it’s just interfering with your ability to eat at your dining room table or use your counters to prepare stuff. So that’s the first thing: It’s taking inventory of what you have. Lots of times, that can be very overwhelming for people. Start to just pick one room in your house and go through that one room, that one corner. People usually pick up speed as they go along and feel more confident. Also, be thinking about the things that you’re bringing into the house.

I love to cook, but I have some items like a nice set of pans that I never use and tell myself I may want to use them later. What are some easy steps to find that distinction between want and need?

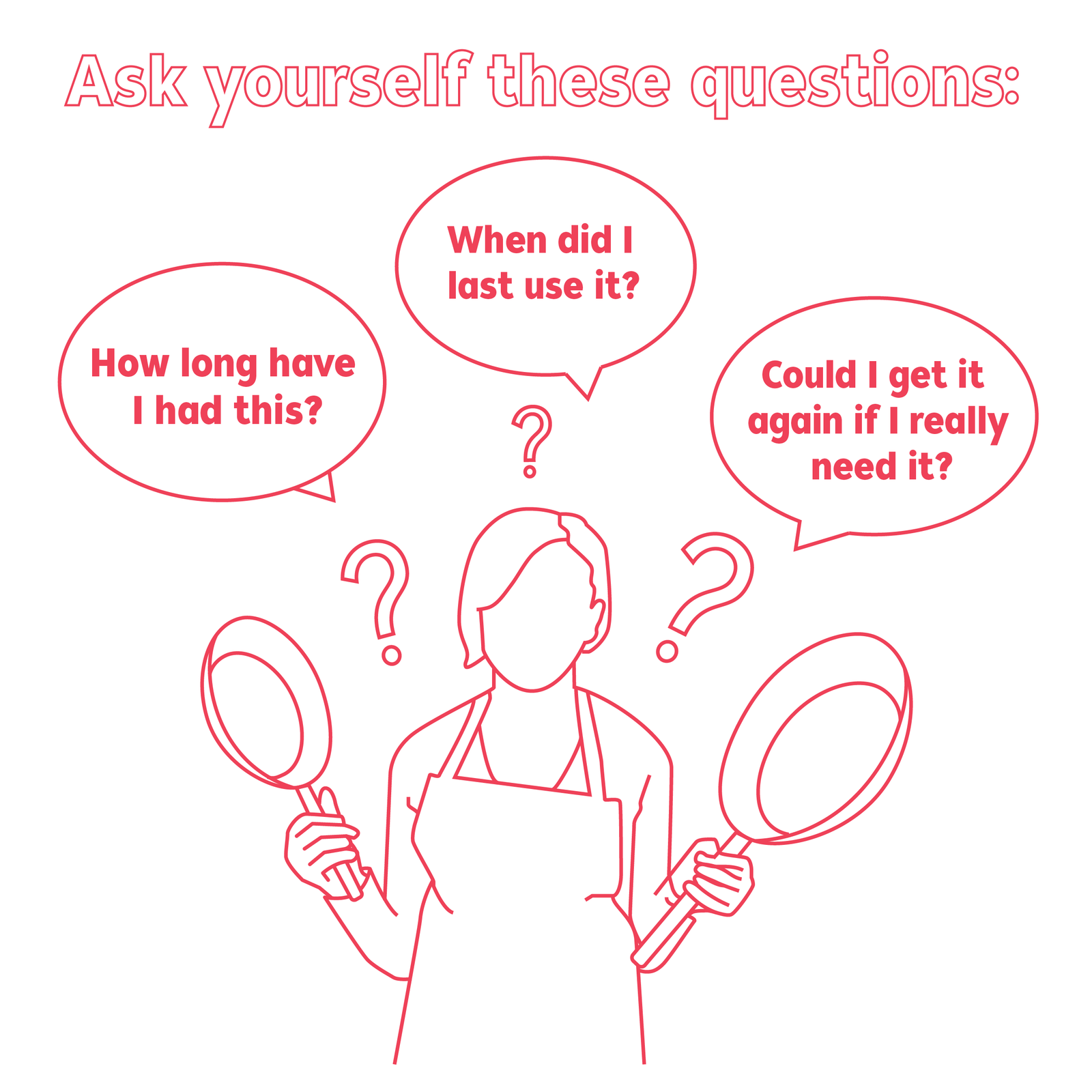

JR: We need food, shelter, and medicine to survive. So think about what your basic survival needs are. You should be looking at everything else as wants. With that being said, there definitely are additional questions that you can be asking yourself. You had just mentioned a set of pans; you may say, “I don’t need these right now, but I intend to cook later.”

If you absolutely decide that in a month or two months you need these pans, it’s probably worth it to go out and buy those nice pans again because you would be really driven at that point. So with the set of pans, it might be great and well to say, “I want to hold onto these, I’m going to use them, I could cook with them,” but the reality is that may be adding to clutter.

Why do we love to hold onto clothes or items from loved ones that we know we probably won’t ever use but we tell ourselves that somewhere down the road we might?

JR: At the base of it, we have evolved as human beings to have positive emotions that are associated with saving or holding onto stuff. There’s the phenomenon know as the endowment effect, which is this idea that once we have this item or own an item, it’s much more difficult for us to let go of that item. We value that item much more highly than we would if we didn’t “own” that item. So there’s a built-in mechanism that we have to save things. When people think about letting go, it produces negative emotions. Common negative emotions are anxiety, sadness, frustration, and anger. Because of those emotions, we create a narrative about why we shouldn’t let go of it. In other words, if I feel anxiety, my mind is much more likely to go to this place of maybe there are probably reasons why I shouldn’t let go of it, even though I know objectively there are probably some good reasons that I should.

Are there ways we can train our brains not to go to a negative place when letting go of items and ways to create habits that promote positive reinforcements when letting go of items?

JR: We always tell people that the best way to manage it is that when you’re letting go of possessions, you may in the short term feel some temporary discomfort, but that eventually passes. We convince ourselves that it’s going to be much more anxiety-provoking or upsetting than it may actually be. If we can let go, we can practice tolerating these emotions, and eventually those emotions dissipate or go away.

What are some of the benefits of being able to positively let go and live a life with less stuff?

JR: I think there are a couple of benefits. In the short term, if they’re able to minimize the number of possessions they have, they just feel better and more comfortable in their living spaces. People are also able to find things more easily [and] organize more effectively. All these things help people to operate more fluidly on a day-to-day basis, which promotes better mental health. But additionally, minimizing the number of items we have creates more room to focus on things that bring us longer-term satisfaction. The less that I’m focused on possessions or consuming things, the more opportunity I have to turn to things that may be reinforcing in the long term, like relationships, spiritually, altruism, hobbies, etc…

How can we can create habits to rationally let go of things and live a decluttered life?

JR: One general rule that ends up being helpful is that when you bring something in, something else should go out...being cognitive of the ebb-and-flow in-and-out of the house and developing systems. Keep in mind how you want your space to look and regularly check in to maintain your space in that way — for example, things like mail or recycling or clothing, set regular times, weekly or monthly, to go through and do a quick sort and make decisions about them so you can keep your spaces clear.

It once took me three years to finally purge clothes in my closet, but once I did it, I had the addictive satisfaction of popping pimples. Seeing the clutter reduced gave me instant gratification. It was easy to get rid of old clothes once I started, but still I struggled to sell my drum. Will my grandma really be pissed that I sold it? Or would she be happy that it got a second life and selling it afforded me something I love even more? Probably the latter. In a moment of clarity and determination I snapped a quick pic of my djembe and posted it to the letgo app. Within five minutes I was chatting with interested buyers, and I had cash in my hand before the end of the day. Hey, if I’m going to accept the death of my (old) dreams, why not sell out for some cash?

Now time to find a new dinner table...

Design by Victoria Reyes / © BuzzFeed

When you're ready to part ways with old items, download the letgo app.