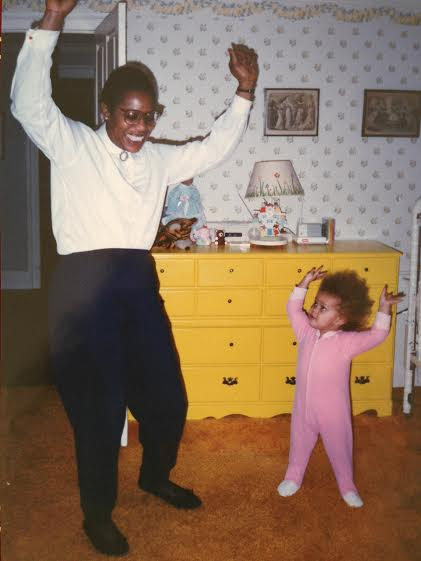

The tangle of blonde-streaked curls that sprouts from my scalp baffled my parents from the very beginning. They were somewhere between my black mom’s tightly wound Afro and my white dad’s European strands — a mass of kinks and coils, constantly attracting playground wood chips and classmates’ curious fingers. In my small, mostly Irish-Catholic town in Massachusetts, it wasn’t long before I noticed I was the only one at the pool party whose hair seemed to magically repel water and inflate to twice its size after air-drying.

My kindergarten and elementary years seemed like an endless journey of discovery for my classmates, who would look on in wonder while I wrestled the mass into tiny scrunchies. Friends would blurt out whatever question popped into their minds. “It’s so fluffy, you could sleep on it. Do you?” “Do you dye it? ‘Cause black people don’t have blond hair.” “How does it dry so fast? It’s like it never got wet!”

I would answer as well as I could (“No, I use a pillow, like you.” “Yeah, but I’m not black, I’m half-and-half.” “I don’t know, OK?!”). But I always felt like an oddity at slumber parties, as the other girls sat in a circle brushing one another’s hair. Whoever sat behind me just picked and prodded at my curls, testing how far they would stretch before springing back into place.

My mom sympathized as much as she could with my complaints that no other girls had my hair, but she couldn’t help lamenting that I didn’t love my curls as much as she did. She made sure that my hair was the star of every family photo, fanning and teasing it out a good three inches past my shoulders. I wish she were here to see how much I love it now.

When my mom died two years ago, she left behind countless unanswered questions. It hadn’t occurred to me until my dad called me, a few months after it happened, that the fate of my hair was one of them.

“Have you found a new hairdresser down in D.C.?” he asked. “Mom would have wanted to make sure you did.”

We half-laughed, because we both knew it was true, and then paused to make room for the pang of guilt that now always seemed to trail laughter. I examined my loosely relaxed hair in the mirror: the inch of new, tousled growth at my roots, the frayed ends. I told Dad I would start my search for a salon that could relax my hair, but I think on some level I had already made the decision not to.

In my newly motherless state, inducted into a community I wanted no part of, I remembered all the time I had spent with my mom in our hair salon, enduring hours in the chair in order to fit into a community — any community — that would accept me. I thought of her unconditional admiration of my hair, no matter what state it was in. I thought of how far I’d come from being the awkward mixed girl on the playground, or the only middle-schooler whose hair wouldn't take a crimp.

I finally felt ready to go “natural,” whatever that meant, and to embrace the part of me that had always felt like such a visible manifestation of my mixed-up identity. I wanted to love the hair that my mom had given me half of, if not as much as she had, then as much as I could.

While my mom had rocked a very chic Afro in her younger days, she started chemically straightening (“perming”) her hair after my brother was born in the ‘80s. As far as I knew when I was a kid, her hair had always been short and straight, and I had always envied it.

For years I begged her to straighten my curls, but she was hesitant to do anything drastic or heat-related herself. The closest she would come was blow-drying, which just made The Puffball, as I called it, even puffier. My constant requests eventually drove her to ask her hairdresser, Celeste, if she thought relaxing my hair would be a good idea. And finally, one Saturday when I was 12, my mom asked if I wanted to come with her to the salon.

The first thing that hit me was the smell, almost like a kitchen: oily and heavy, and a little bit burnt. But when I walked in, I felt like I was entering a secret grown-up club, for grown-up ladies. Mom even let me choose any magazine I wanted, from the very same ones she insisted were “too mature” when I reached for them at the grocery store. I went with Glamour.

Best of all, everyone adored my hair, and not in a way that made me feel like an alien. They didn’t pick or pat, but rather stroked and fawned over the golden highlights. I was in a black hair salon surrounded by older black women I already respected and admired, and they thought my hair was beautiful.

I was nervous, but this was what black women did, right?

Celeste sat me down in her cushy black leather salon chair and explained how she would be “relaxing” my hair: “We’re not going to get rid of your curls, we’re just gonna make them chill out, loosen up.”

She set out a bucket of yellow-beige goop and proceeded to coat my scalp with Vaseline. She explained that this would protect my skin from the chemicals in the relaxer, which I hadn’t been worried about until I realized I would need protection from them. Mom assured me Celeste knew what she was doing, and all I would feel was occasional tingles. I was nervous, but this was what black women did, right? If all these women survived unscathed, I was assured I would, too.

And I did, for the most part. By the time Celeste had sectioned and coated my scalp in the oddly cold goop, the tingles had begun to escalate into sharp pinpricks. But she blessedly rinsed and conditioned my hair just in time, before cinching it all into big rollers and guiding me to a spot next to my mom under one of the sit-down dryers.

“Now you just sit tight for about…” Celeste reached above me and turned a knob I couldn’t see. “Let’s say...50 minutes.”

I was more than willing to deal with the upkeep of relaxed hair if it meant my best friend could French-braid it for soccer.

I looked at her in disbelief, but she just handed me the Glamour I had already read and walked back to another customer. My mom reached over, squeezed my hand and half-shouted over the dryers that she was proud of how well I’d done. So I settled under the dryer, resigned to my fate, and re-read a cover story about the comeback of Vivica A. Fox.

As I would many times over the next decade of my life, I nodded off under the dryer. Celeste woke me when it was time and led me back to the chair. She unraveled and blow-dried my hair (“You have to dry it again?” “For the finishing touch, yes!”) for what felt like ages.

When she spun me around I laughed out loud in delight: My hair was straight! She had left a lot of volume, and I would learn to ask for smaller rollers, but I was thrilled to finally join the ranks of the smooth and silky.

When I showed up at school that Monday, it was like elementary school all over again. (“How did you get it so straight?” “How long did it take?” “Is that a wig?”). I was frustrated that every compliment came with a follow-up question, and sure, I still had the year-round tan, but I was one huge step closer to fitting in. I bought a brush and flat iron. I was more than willing to deal with the upkeep of relaxed hair if it meant my best friend could French-braid it for soccer.

I continued relaxing my hair for the next 10 years, and whenever I needed a touch-up, about every three months, I would go with Mom to Celeste. When I started college, Mom and I would meet up in Boston at a new salon she had found after diligent research through black friends whose hair she admired.

There I worked with Danielle, who was funny and talkative, while Mom preferred Sabrina, an elegant Sudanese immigrant who loved mourning the decline of society and telling Mom she had perfect skin. I looked forward to going, in spite of the goop (which I actually loathed), because I loved spending time like this with Mom: surrounded by fellow black women, feeling like we could tell our deepest, darkest secrets and not only would everyone keep them, but they would probably have the same secrets, too. For those few hours on Sunday morning, I felt intimately bonded to the community my mom came from, which had always seemed just out of my mixed-race reach.

It felt as though I had to pick a side — that one part of my race would always be a descriptive but ultimately superfluous adjective, and the other would be the tangible, indisputable noun.

Growing up, I received constant mixed messages about my racial identity. Friends and classmates would ogle my hair and admire my skin, but jokingly call me "Oreo" and ask if I considered myself more of a black white girl or a white black girl. It felt as though I had to pick a side — that one part of my race would always be a descriptive but ultimately superfluous adjective, and the other would be the tangible, indisputable noun.

I had never felt particularly cut out for the role of "black girl" as I understood it, and I didn't think of my curls as anywhere near what I considered to be “black hair.” So I had relaxed them to ease my acceptance into the overwhelmingly white community I lived in. But in doing so, I ended up gaining a deeper knowledge of the black community, finding other women whose relationship to their hair was as layered as my own.

By the time I reached college and found a multicolored community in a diverse city, I still relaxed my hair, but had taken to letting it air-dry, striking a balance I felt comfortable with. I ended up with an appropriate contradiction of straight ends and curly roots, which did the work of conveying my confusion for me.

After losing the most enthusiastic and devoted source of unconditional love in my life, I had to start supplying my own.

It wasn’t until I was standing in front of the mirror, after hanging up with Dad, that it seemed obvious: Relaxing my hair for so long was just doing what I had always done, trying to tread the intangible line between black and white. But I was sick of the confusion. I had never taken the time to understand and appreciate my hair, and now it was starting to feel as though I had never taken the time to understand and appreciate myself.

I know that by bringing me with her to the salon, Mom was only ever trying to make me happy, to make me feel like I fit. But I realized that I no longer needed that. After losing the most enthusiastic and devoted source of unconditional love in my life, I had to start supplying my own. I wanted to be just what I am: a mulatto with a tangle of blonde-streaked curls.

And if suddenly no community wanted me — black, white, mixed, brown — then at least they would reject the version of me I actually wanted to be.

It has been indescribably liberating to let my hair be: to let it do what it wants, to stop fighting it. The actual transition was pretty smooth — a casual metamorphosis in plain view. I simply shepherded in my new growth with lots of detangling and tons of conditioner. It never felt like a political statement or drastic turning point: It felt, well, natural.

That isn’t to say it’s been seamless. The coils seem to have amplified with a vengeance since my childhood, and the monthly inquiries regarding whether I’ve cut my hair (followed by polite yet vacant nodding when I explain that it’s just shrinkage) have become predictable. But it’s worth it.

I’m now as fascinated by my hair as my friends have always been, tugging at spirals and piecing apart young, ambitious locks. I am learning to appreciate my hair’s unique temperament and color, its unwillingness to conform to any of the myriad categories lining the hair-care aisle. It’s helped me stop worrying that I need to pick a side. I can look in the mirror and feel, finally, relaxed.