Why is everyone talking about grammar schools again?

When Theresa May entered 10 Downing Street in July, she pledged to end the "burning injustice" suffered by people across Britain, particularly poorer people who seemed to miss out on opportunities enjoyed by their privately educated contemporaries.

One of the ways she is seeking to do this is by lifting the 1998 ban on the expansion and creation of grammar schools, which children can attend if they pass an entrance exam at the age of 11, known as the "11+".

The "Tripartite" selective system, which was introduced in 1944 and scrapped in 1965, saw the highest-achieving children attend grammar schools, while the rest received a more skills-based education at a secondary modern or a technical college. By the 1980s, most schools had been converted to non-selective comprehensives, where children of all abilities are taught from the same curriculum together.

One hundred and sixty-three grammar schools, however, still exist, mainly in Buckinghamshire, Kent, and Lincolnshire, where 166,000 children – around 5% of the state school population – are educated.

Now May thinks we should reverse the ban on new grammar schools imposed by Tony Blair's Labour government and open more such selective schools, as well as allow high-performing non-selective schools to convert to grammars so more children can access a "good" school place.

A return to grammars is a stark contrast to previously proposed plans to turn all schools into independently-run academies by 2022. That legislation, which would have seen the expansion of a system which thrived under David Cameron's leadership has now been formally scrapped by May's government.

But what does increased selection mean for children who don't get into grammar schools, and does every child have equal access to them, no matter what their background?

The Department for Education's proposal document, Schools That Work for Everyone, says grammars would be forced to support their non-selective counterparts so that even children who don't pass can enjoy a high-quality education.

"These policies will increase the number of good and outstanding school places in

the system, and therefore should benefit all students," the consultation document states.

Many parents will no doubt relish the increased opportunity to get their children into grammar schools, which, statistically speaking, produce much better grades than comprehensives, but not everyone is on board. Independent think tanks including the Education Policy Institute (EPI) and the Institute for Education argue that selection disadvantages far more people than it helps, especially poorer children, who have a much slimmer chance of getting into a grammar.

"Why are we not just striving for excellence in all our schools rather than saying, 'Let’s create this elite 20% and the rest of the kids can take one for the team'?" Rebecca Hickman of Local Equal Excellent, a campaign group seeking the abolition of grammar schools in Buckinghamshire, told BuzzFeed News.

"Twenty per cent get their lovely opportunities, whereas it should be about excellence for every single child."

Are grammar schools better than other schools?

Based purely on attainment data, it certainly looks that way. 96.7% of grammar pupils achieved five A*-C grade GCSEs compared to a national average of 57% in state schools, according to the EPI. After grammar schools expanded in Northern Ireland in the 1980s, the average number of pupils getting three or more A-levels rose by 10%.

There is also some evidence that pupils who attend grammar schools go on to do better and earn more after they leave school.

But while it's clear pupils do do well at grammar schools, there's also a lot of evidence that the advantages only apply to a minority of students, and that pupils in highly selective areas who don't get into a grammar actually do worse than those at comprehensives elsewhere.

"I do think students can benefit from selective education but I firmly disagree with it as it does not benefit the vast majority," Helen Duncan, a teacher at Our Lady’s RC High School, a non-selective school in north Manchester, told BuzzFeed News. "In fact I believe it negatively impacts the students in the comprehensive system by removing the most able students."

According to the EPI, children who don't get into grammar schools in highly selective areas achieve lower GCSE grades on average than the lowest achievers in non-selective areas. The impact is even greater for non-grammar children receiving free school meals (FSM) in selective areas, whose GCSE grades were on average lower still.

When EPI compared top achievers in grammar schools with high-attaining pupils from the best non-selective schools, they did just as well as each other.

So while there's no doubt that grammar schools are good for some children, they seem to be worse for a lot more.

What happens to the kids who don't get into grammars?

Pupils who don't pass a grammar's entry exam will go to a non-selective secondary school, where the same National Curriculum is taught.

Education secretary Justine Greening recently told parliament that she does not intend to replicate the grammar and secondary-modern model that dominated in the 1950s and '60s. "There will be no return to the simplistic, binary choice of the past, where schools separate children into winners and losers, successes or failures," Greening said.

Instead, funding for new or expanding grammar schools would depend on them setting up partnerships with non-selective schools, the government has said. Grammars would be expected to support non-selective schools to ensure all children received the same high-quality education, regardless of which school they attend.

While plans for what these partnerships might look like has not been detailed, suggestions include the sharing of teaching and facilities between the two types of schools, or "buddying" programmes, where children from non-selective schools can access support with GCSE revision and university applications.

A new "tutor-proof" entrance exam is said to focus on a child's "natural ability" and therefore prevent children whose parents could pay to have them coached for the test from gaining an advantage.

But where grammar schools are already prevalent, the children who are getting into them are not the ones from poor backgrounds, and children attending the non-selective schools in those areas don't do as well.

What's more, London-based primary school teacher Pericles Hatzikiriakidis told BuzzFeed News that the rigorous testing of 11-year-olds has a serious impact "on the children's confidence and their faith in their skills".

Hickman worried that children who failed the test would "feel crushed and have had their self-confidence knocked at one of the most important points".

If entry is based on intelligence alone, doesn't a poor kid have the same chance as a rich kid of getting into a grammar?

A lot of research suggests otherwise.

In a report for the BBC, journalist Chris Cook compared the prosperity of neighbourhoods in Kent against the number of children from those areas who attended a grammar school. He found that children in the poorest areas had a less than 10% chance of getting into a grammar, while the highest instances of grammar school attendance were in the richest areas.

"Poorer students are significantly less likely to attend a grammar school," according the Institute of Education. Its research showed that in highly selective authorities, around 17% of children were entitled to free school meals, but only 3% of those children attended grammar schools. This compared to around 18% of children at state schools receiving free school meals.

It also found that between 12% and 20% of children at grammar schools had attended a private primary school, whereas only 2% of children in state secondary schools had come from the independent sector.

Several parents BuzzFeed News spoke to whose children had sat the 11+ also felt that without extracurricular support, such as private tutoring, it would be impossible to pass grammar school entrance exams. Private tutoring in the UK costs around £30 per hour.

Teacher Helen Duncan, who said she believes increased selection "perpetuates elitism and will further emphasise class divides", also felt that a lack of access to coaching could be a barrier to some poorer children getting into grammar schools.

"The problem with the 11+ is that many middle-class children benefit from increased 'education' at home in terms of support from parents such as reading at an early age," she told us. "Therefore it isn't necessarily that those students who go to grammar schools are more 'intelligent', but simply more advanced at that stage."

The government has however pledged to do more to help the less advantaged get into grammar schools, including requiring selective schools to admit a minimum number of children from poorer backgrounds.

The Schools That Work for Everyone proposal sets out aims to expand the measure of which children fit into this category so it doesn't just include children receiving FSM, but also takes into account those who are "just about managing".

But in a recent House of Lords debate on the grammar proposals, Labour peer Baroness Andrews still had doubts that increasing selection would aid social mobility.

"The great meritocracy is, I fear, a great illusion," Andrews said.

"It advantages children already in grammar schools and disadvantages children in the rest of the schools.

"How could it be otherwise, given that Michael Wilshaw, chief inspector of schools, has said recently that if someone had opened a grammar school next to Mossbourne academy he would have been absolutely furious?"

Wilshaw, the head of education regulator Ofsted, had said he believed having high-achieving children in every school helped set the a tone of success that would boost the learning of those who were less able.

"Youngsters learn from other youngsters and see their ambition, which percolates through the school," Andrews said.

The fact that grammar schools are full of richer kids means that they end up getting better funding.

"There’s very clearly a funding gap between high schools and grammars," a father from Kent whose daughter is at a grammar and whose son is at a non-selective school told BuzzFeed News.

Grammar schools often have strong networks of former pupils, and a disproportionately large number of current pupils come from higher-income households, which offers ample fundraising opportunities.

A mother from Buckinghamshire who has one daughter in a grammar school and another at a non-selective school told us she had recently attended a parent conference at the grammar school where fundraising was discussed.

"[The school] told us that they had £80,000 worth of money coming in from parents, ex-parents, alumni, and friends of the school with very deep pockets who are donating huge amounts of money," she said.

With this money the school was able to fund things such as "resilience" sessions to prepare children for their forthcoming GCSEs, as well as extracurricular activities including a range of choirs for pupils to join.

"The following day I went to the quiz night at the secondary modern and the whole feeling was completely different," she said. "They were so grateful for every single penny they could raise. The difference is incredible."

The father from Kent had noticed the funding difference creeping into the academic opportunities his son had available at the non-selective school too.

"[His son's school] can’t afford the staff to provide a drama GCSE, and my son is quite dramatic, so it would have been perfect for him," he told us. "He would like to do drama, but he just literally can’t do it because they school can’t offer it."

Aren't grammar schools quite popular with parents though?

A recent survey of 1,000 parents by Mumsnet found there was no general consensus on grammar schools among its members. While 37% were in favour of selective education, 40% were opposed to it, and 23% didn't know what to think about grammars.

Whichever side of the fence they sit on though, parents seem to feel very strongly about the subject.

"I am passionately pro-grammar schools," one mother whose two children attend a selective school told us. "I'm disabled, poor as a church mouse, live in a very deprived area and have very bright children. Grammar schools have given my children a way out of the poverty they live in."

An anti-grammar-school campaigner from Manchester told us that when she held street stalls demonstrating against selective education, some parents she met praised local grammars for having raised house prices in their area, and said they felt their children benefited from being educated alongside those of similar abilities.

Hickman believed that while many parents like the idea of grammar schools, they can start to look less appealing when the realities of selection hit home.

"I think that they are very popular with parents up until the point that parents are in the system," she told us. "Too often the parents who like the idea of grammar schools don’t realise that you have to spend a fortune on tutoring, and all sorts of other things that children should be doing with their lives don’t actually happen because their childhood for several crucial years just becomes about passing the 11+."

So what happens now?

The government's grammar school proposals will remain in consultation until December, and draft legislation will be published next spring.

Ministers will have to get the bill through the House of Lords and the House of Commons, which remain heavily divided on the subject.

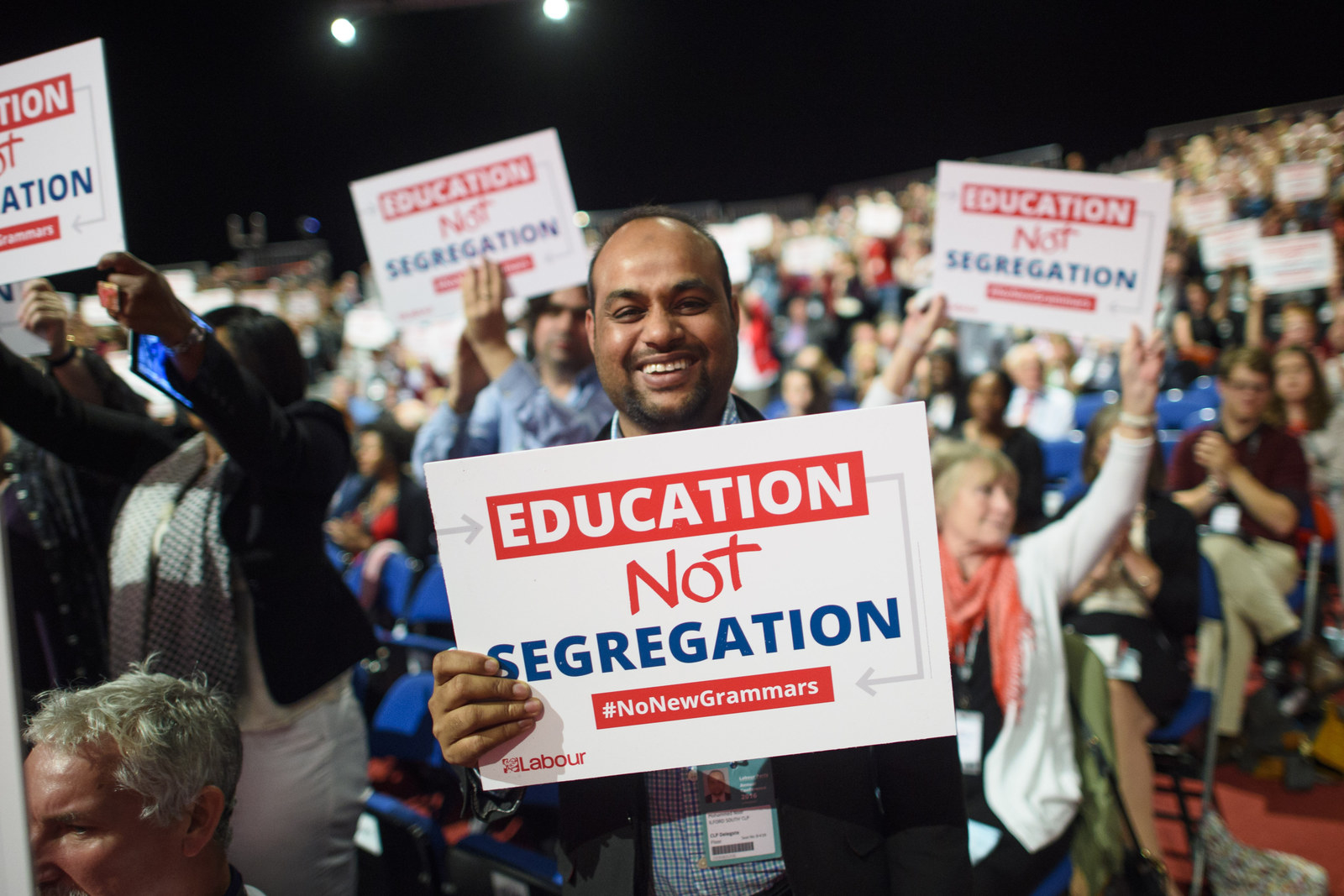

While many parents would welcome a return to a selective system, there are also plenty who wouldn't, and grassroots campaign groups such as Comprehensive Future continue to lobby against them.

But May, who herself was educated at a grammar, is sticking to her guns.

“I get challenged in the House of Commons by those who say to me: ‘Where is your evidence that grammar schools make a difference?’ But I would say to all of you that you can give us the evidence,” May told supporters of selective education during a Friends of Grammar Schools reception at Westminster recently.

"Sadly, too many children in this country today are still at schools that are not good or outstanding," she continued.

"As we look at ensuring that we increase the capacity of school places, that we increase the number of good school places across the country for children to give them those opportunities, it is to me obvious that we must look at grammar schools.

"Because if you said to somebody that there was legislation in the UK that stopped good schools from opening or expanding, they would say: ‘What on earth are you doing?’"