Health secretary Jeremy Hunt has laid out "an ambitious plan to expand the mental health workforce" that aims to explain how the government would achieve its previous pledge to provide the same standard of mental health care in the NHS as it does physical health care by 2021.

"We know we need to do much more to attract, retain and support the mental health workforce of the future – today is the first step to address this historic imbalance in workforce planning," Hunt told BBC Radio 4's Today programme in an interview launching the plans.

The proposals include an additional 4,600 additional posts for nurses and 200 more therapists working in crisis-care settings, as well as the recruitment of 2,900 therapists and allied health professionals who would help increase access to talking therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy.

Hunt also said there were plans to improve perinatal mental health services, which have recently come under fire. A report by the National Childbirth Trust in June showed that many women who had recently given birth were struggling to access the relevant mental health services as a result of a lack of GP provisions, and midwives not having received sufficient mental health training.

Read the plan & watch Prof Ian Cumming talk about investing in the mental health workforce https://t.co/h1Z9rFKNXc… https://t.co/u8ZfCZ5Az5

Key to Monday's announcement was the announcement of plans to recruit more mental health staff in child and adolescent mental health services, including the creation of 2,000 additional posts for nurses, consultants, and therapists.

In January, prime minister Theresa May pledged to focus attention on the improvement of mental health services for children and teenagers, who are disproportionately affected by mental illness, although critics at the time said this would not be possible without a substantial increase in funding.

The government has pledged £1.3 billion of funding to achieve this, which was originally announced in February.

But there is concern that previous staff losses across mental health services, as a result of austerity and poor staff retention, means that the number of new staff will not be sufficient to boost the overall workforce in real terms.

Gov workforce plan for mental health sounds good but they promised 5,000 more GPs & numbers are falling. Without more funds it is a fantasy

Warnings have also been issued by professional bodies, including the Royal College of Nursing and the British Medical Association, that a steady decline in recruitment as a result of the introduction of nurses' bursaries, the public sector pay cap, the potential loss of staff who are EU nationals – who make up a substantial portion of the workforce – and more junior doctors choosing to specialise in areas other than psychiatry would make the numbers unachievable.

Here's why the real number of mental health staff the government will be able to recruit by 2021 might not actually add up to the numbers it hopes to achieve.

The number of nurses working in the NHS is already in decline, and even fewer new ones applied to train this year.

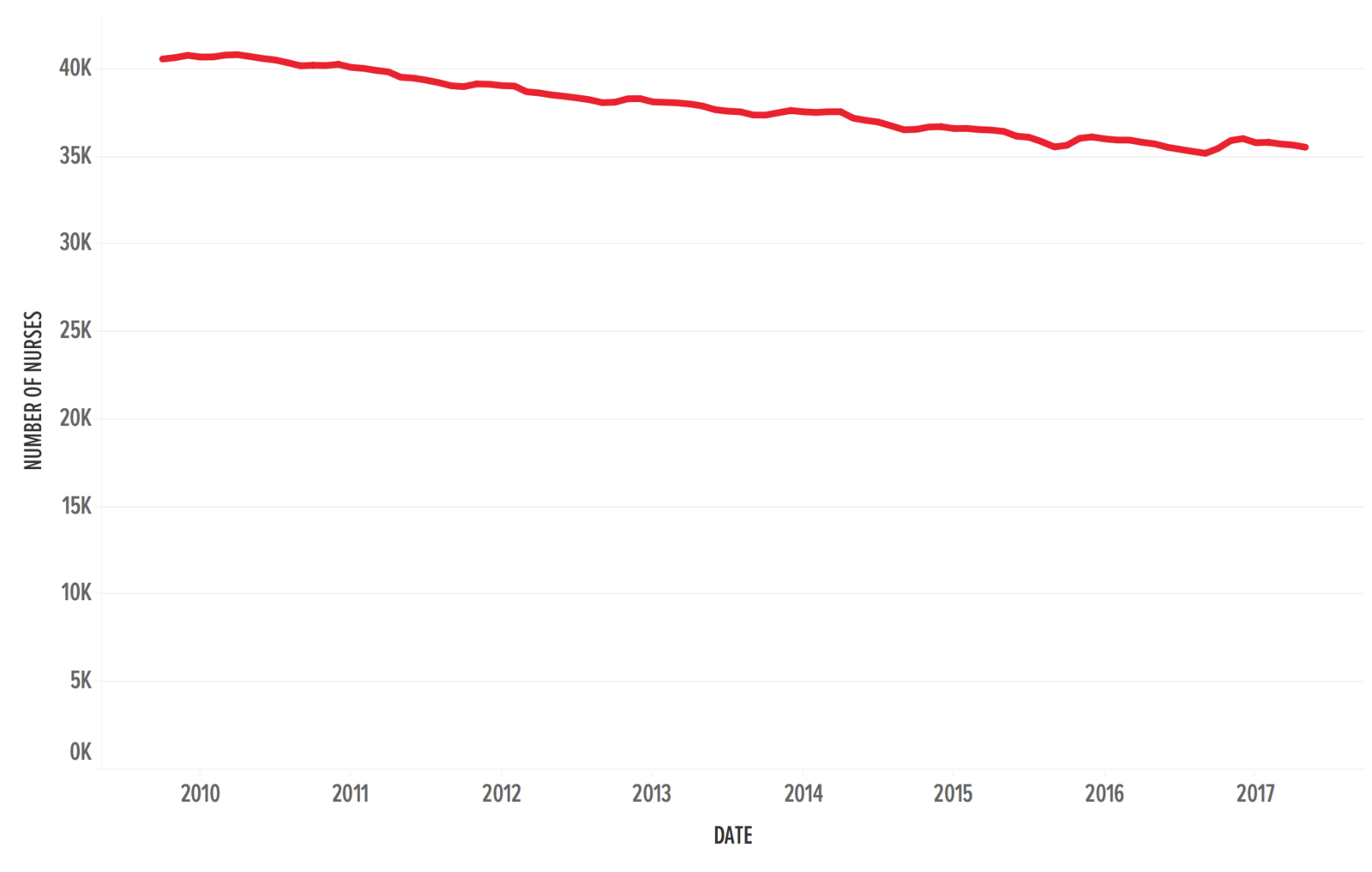

The number of nurses working in the NHS and the number of new students applying to work as nurses in the NHS have been in steady decline since 2010.

In April 2017, there were 35,563 mental health nurses working in the NHS compared to 40,744 in April 2010, the month before the Conservative-led coalition government came to power.

The 4,600 crisis mental health nurses the government hopes to recruit would only just bring the number back up to 2010 levels if a steady number of students signs up to train in those roles – but the number of new student nurses overall is in decline.

Last year it was announced that the nurses' bursary would be scrapped from September 2017, which means that student nurses will be required to take out large student loans rather than receive government funding for their training.

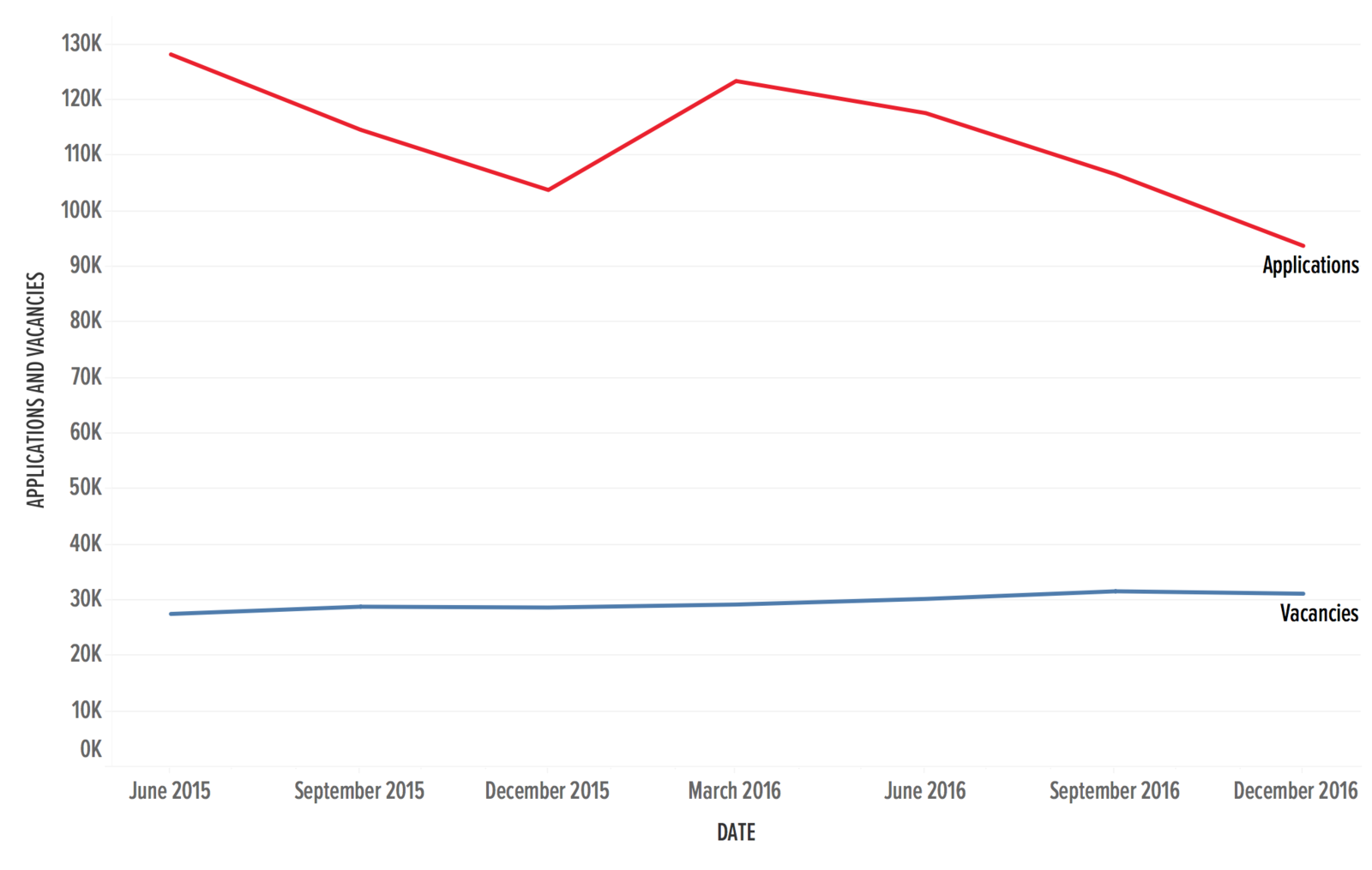

Applications for nursing and midwifery courses for the 2017–18 academic year fell by 23% according to UCAS, with 93,779 applications received in December 2016 for nursing courses compared to 103,826 in December 2015 – again, despite an overall increase in the number of places.

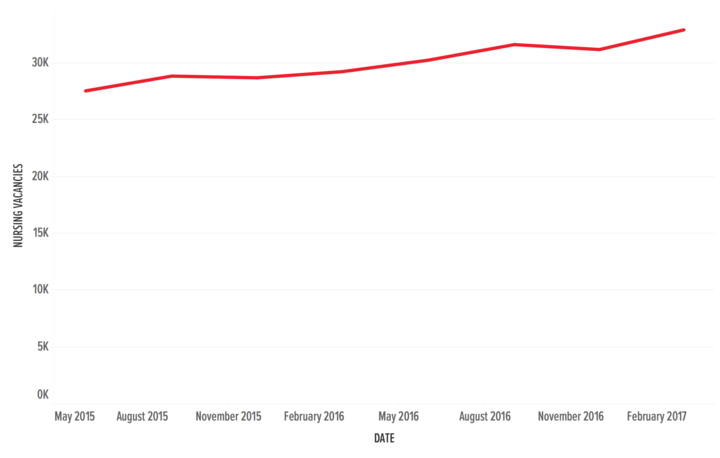

In addition to this, the number of nursing vacancies in the NHS – for mental health and general care – has increased.

The Royal College of Nursing has been critical of the proposals, which its chief executive, Janet Davies, does not believe will be sufficient in delivering the number of nurses needed to achieve better mental health care.

"There is already a dangerous lack of workforce planning and accountability and this report is unable to provide detail on how the ambitions will be met," Davies said.

“It is clear the government will need to work hard just to get back to the number of specialist staff working in mental health services in 2010.

"Under this government, there are 5,000 fewer mental health nurses and that goes some way to explaining why patients are being failed."

Davies welcomed the government's recognition that more staff are needed, but said that "hard cash" is necessary to realistically deliver this. "The government’s policies appear not to add up," she said.

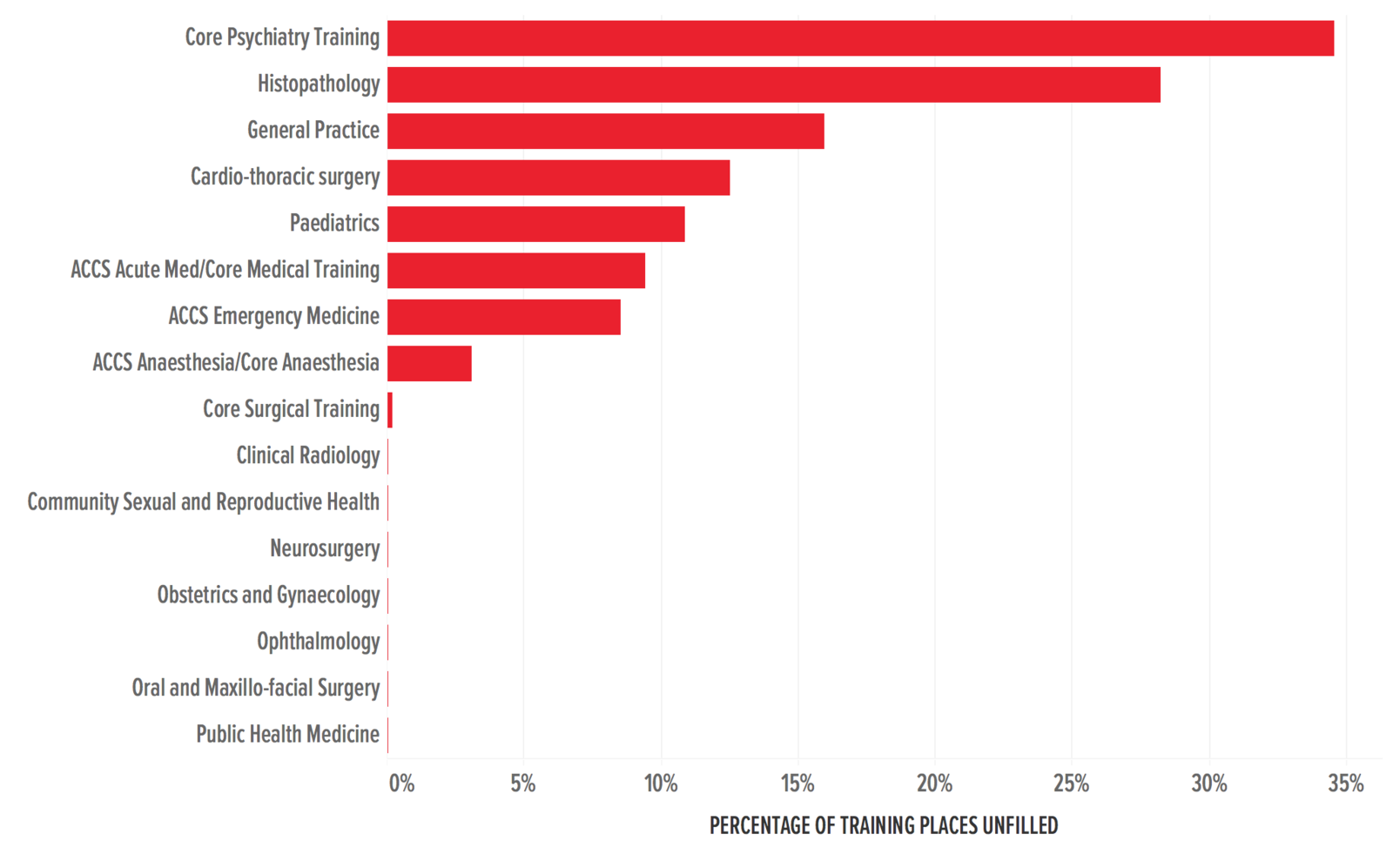

Not as many junior doctors are deciding to specialise in psychiatry, meaning that fewer will end up qualifying as consultant psychiatrists.

According to the British Medical Association, fewer junior doctors are opting for psychiatry when choosing their specialisms.

Figures released by Health Education England, the body responsible for training junior doctors, show that the number of doctors taking up psychiatry training places had fallen by almost 20% between 2016 and 2017, despite the overall number of available training places actually increasing.

"There has been insufficient recruitment of psychiatry trainees across England and a high percentage of trainees do not complete training in the specialty," a BMA spokesperson said.

Referring to a 2015 workforce planning report by health think tank the Kings Fund, they added: "In 2014, one in five doctors undertaking core psychiatry training did not progress into the final part of their training."

The Department of Health plans to announce a targeted campaign next year to encourage more trainees to specialise in mental health. This will include a "two week taster programme" and an increase in the availability of psychiatry rotation placements for junior doctors completing the foundation stage.

But while the government may be keen to train more psychiatrists, if fewer of them choose to take up the training, there will be a reduced number of doctors eventually qualifying as consultant psychiatrists.

Brexit could mean that EU nationals currently working in mental health services decide not to stay in the UK, and it might become harder to recruit qualified doctors and nurses from outside the country.

One of the greatest risks posed to staff retention in the NHS overall is whether or not the large number of EU nationals working in the health service will choose, or be able to, continue to do so after Brexit.

While details of what Brexit will mean for EU nationals will remain unclear until negotiations are complete, the Department of Health says it is keen to ensure NHS staffing is protected, particularly in mental health.

"As part of Brexit preparations Health Education England is focusing their international work on four key areas with mental health as one of these, alongside primary care, urgent care and cancer," a spokesperson said.

"As we have repeatedly made clear overseas workers form a crucial part of our NHS and we value their contribution immensely – and the future of those EU nationals working in our health and care system should be a priority in Brexit negotiations."

Mental health services would stand to see a substantial decline in nurses if Brexit restricted their ability to work in the UK. In March 2017, when the Brexit process began, there were 38,024 mental health nurses who are EU nationals working in the NHS compared to 16,798 in March 2013.

The Department of Health has said that it hopes to recruit new mental health staff who have already qualified.

In June this year, the Nursing and Midwifery Council reported figures which showed a 96% decline in the number of qualified EU nurses registering to work in the UK, which is thought to be a result of Brexit.

Low morale and little opportunity for improved pay could detract people from wanting to come to work in the NHS.

2016 was a tumultuous year for the NHS, with doctors going on strike for the first time since 1974 over a dispute about their pay and working conditions, while the announcement of the scrapping of the nurses' bursary further angered a workforce which already claimed it was overstretched and underpaid.

The start of 2017 saw the worst winter A&E crisis for years, which the British Red Cross called a "humanitarian crisis" after reports emerged of people dying on trolleys in hospital corridors while they were waiting to be seen by doctors.

.@Jeremy_Hunt says workforce numbers growing but he concedes "we need more." Welcome recognition, but we lack detailed plans for whole NHS

Following June's general election, in which the Conservative party was narrowly returned to power, the new parliament was dogged by rows over the public sector pay cap, which MPs voted to keep at 1% despite rising inflation.

A shortage of GPs, even after the government had pledged to increase the number of doctors working in general practice, left the workforce even more distrustful and disillusioned.

“Jeremy Hunt called for thousands of extra GPs to be in place by 2020, yet so far he has overseen a shrinking of the workforce. They then quietly dropped the commitment in their manifesto. And now he has already been forced to admit that he hasn’t got the money for his latest plans," said Norman Lamb, the Liberal Democrats' health spokesperson.

"We need to be serious about mental health but all this government has done is pluck a number out of thin air. This is a government that is all bark and no bite."

But today's news involves no more resources than already planned. Have become v cynical of these 'numbers' announce… https://t.co/WyTglVbdui

In May, NHS Providers chief executive Chris Hopson said that "significant" numbers of lower paid NHS staff were quitting to work in supermarkets as a result of government pay restraint.

According to the Royal College of Physicians, 44% of the consultant physician posts advertised were unfilled last year as a result of an insufficient number of junior doctors completing their training. The British Medical Journal cited poor morale and insufficient workforce planning as key reasons.

The Department of Health has said it hopes to recruit from 4,000 psychiatrists and 30,000 trained mental health nurses working outside the NHS to ensure its numbers of new staff are met by 2021.

Heath Education England will lead a major “Return to Practice” campaign, working with NHS Employers to develop more flexible and supportive working environments, and help more of them draw on the skills of recent retirees.

Hunt remains confident that these new proposals will bolster the mental health workforce in the NHS, and improve mental health services overall.

“Look at our track record,” he said on Radio 4 on Monday.

“If we want to transform mental health provision, we have to be strategic about this."