Last Tuesday night, after watching the electoral map devolve into a red blur, I bolted to my feet and dug through drawers and cabinets in search of my emergency stash of cigarettes. At 1 a.m. in Los Angeles, I sat in my backyard, in the dark, numb. A friend called, sobbing. My sister called, hysterical. I sat very still, pulling on my cigarette, debating whether or not I should light a second right after the first, wondering if I had it in me to become the first woman who stayed in her backyard smoking cigarettes for four years, never moving, never wavering.

Over the past few years, my work for Everyone Is Gay — an organization I co-founded that provides advice, laughter, and resources to LGBTQ young people — seemed to take on a different tenor. While LGBTQ youth were certainly still in need of seeing themselves represented in the world, my outreach started to seem a little less urgent. Young people, more and more, were jumping in and supporting each other directly, commenting on our posts and advice questions with resources that had helped them in the past, and resources that they themselves had created. That was a powerful and comforting feeling.

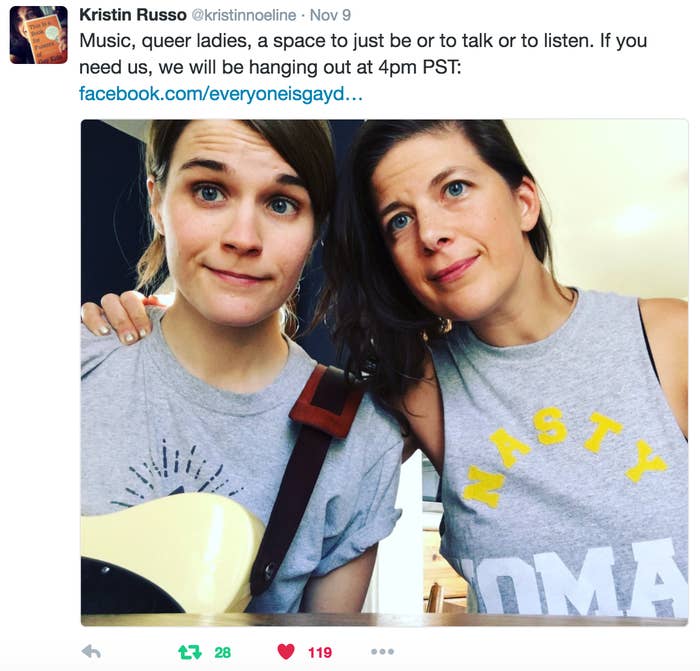

But as I moved from my couch to my drawers and cabinets, from my drawers and cabinets to my backyard, from my backyard to my wife’s arms, and from my wife’s arms to a fitful night of sleep, I realized how wrong I had been to consider comfort or complacency. I had celebrated marriage equality, our military’s increased inclusion of LGBTQ people, the rise of queer and trans characters in our media, LGBTQ youth’s unwavering demands for respect, resources, and validation — but I forgot that a powerful pendulum can swing back in the other direction. And so, when I woke up the next morning, I put out a call to the many others who had similarly found themselves in a sea of confusion and grief, to the countless young LGBTQ people who were feeling betrayed and alone: Come, join me and my wife, share space, share conversation, share music.

We weren’t sure what we would do or say, but we knew we needed community. And so, at 4 p.m. that afternoon, my wife and I started a Facebook live event and sat together in solidarity with hundreds of LGBTQ youth. While the advice I had given to these young people in years past had been sourced from my own, lived experience, now we were tasked with facing our grief and fear together, in real time. Our eyes were collectively wide, looking at a forming administration made up of people who, among many horrors, had vocalized support for conversion therapy, vowed to (then flip-flopped on) upending marriage equality, and declared the rights of transgender students unimportant to the federal government. LGBTQ young people joined us and wrote in from across the country and the world — from Tennessee to Pennsylvania, from Kansas to Rhode Island, from Georgia, California, Virginia, Arkansas, New York, and Idaho to Belgium, Spain, Sweden, the UK, and Australia. I listened to their concerns, their worries, and their anger, and this is what I told them:

“It doesn’t feel like we belong here anymore.”

As we watched the sheer number of individuals in our country confirm, with their votes, that we did not matter — either enough or at all — we were also sent the very real message that we were not deserving of our government’s respect or protection. Instantly, countless spaces felt infinitely less safe for our community. (I would like to acknowledge that these words are coming from a white, queer, cisgender woman who walks with much more privilege than my gender-nonconforming, trans, POC, and Muslim friends, many of whom are afraid to go to work, go to school, leave their homes.)

"We are here. We belong here. This is our space. We demand better."

I believe that we owe ourselves the space to feel that sadness, that fear, and that isolation. I also believe that it is critically important to listen to the many voices rising up right now to scream: No. We are here. We belong here. This is our space. We demand better.

I urge you to surround yourself with those voices. If you can be one of those voices, please join us in shouting. Take to the streets if you have the means, take to social media if you are able. If you cannot join us in our public outcry, please do not judge yourself; instead, curl our voices up around your body, know that there are millions who will fight for you because we know that you belong, that you are deserving of love and respect, that you matter, and that you are infinitely important to the well-being of this country.

“How do I deal with toxic family members, who are happy with the outcome, and how do I deal with having to see them over the holidays?”

A week before the election, I wrote an open letter to my extended family who I feared were voting for Trump. As my fears were confirmed, and as I began to find myself faced with their hurtful comments and questions, I quickly understood that I did not have the ability to engage with them further. It cut too deeply, and it hurt too much.

I am 35 years old, and I live with my wife, so while this process has taken me to my knees with grief, I am able to protect myself by keeping distance between those family members and myself. This, too, is a privilege that I do not take for granted. Many of you out there do not have the option of space; many of you are still living with parents who are happy with this election’s outcome, and who speak openly about that happiness — sometimes knowing, sometimes not knowing who you are, or how much pain you are experiencing. Many of you have to face this with the added insult of having been too young to cast a vote yourselves.

"You are not alone. Thousands upon thousands of young LGBTQ people will be navigating these waters."

First, know that you are correct: This experience is toxic. I am so sorry that you have to experience it — no one should.

Next, do not engage. If you are with family and these issues come up, you can leave the room. You do not have to explain yourself, and you also do not have to out yourself. If you need an excuse, just explain that talking politics is very stressful — especially right now — and you don’t want to be a part of it. If anyone asks you a politically charged question, change the topic. “I don’t really like talking politics over the holidays, but you should go see the pie mom made for dessert.”

Finally, surround yourself as much as possible with support. When you can, text your friends, connect with people who value you and who understand how hard this experience is for you. You are not alone. Thousands upon thousands of young LGBTQ people will be navigating these waters this holiday season.

Should things feel unbearable, know that resources like The Trevor Project and Trans Lifeline are open 24/7 and are always there to help.

“I’m so sick of people telling me I am overreacting to this.”

My friends: Anyone who would dare tell you that you are overreacting has a deep misunderstanding of how discrimination and marginalization impacts individuals and communities. I have personally experienced many iterations of this harmful misunderstanding over the past few days. When I have expressed fear, I have been told to relax because my life “wouldn’t be any different,” and when I have expressed horror at electing a person who would campaign on hatred and divisiveness, I have been told that “words are not the same as actions.”

I reject this — all of this — as should you.

We are the only ones who can know the truth of what we feel, and our hurt and sadness and anger are not only justified — they are imperative to necessary action.

"We are the only ones who can know the truth of what we

feel, and our hurt and sadness and anger are not only justified — they are imperative to necessary action."

To those who say our lives won’t be different post-election? Our lives already are different. We have lost family. We have a heightened fear of coming out or staying out. We are facing elected officials and members of their transition team who have said clearly and repeatedly that we should not be entitled to basic human rights.

To those who counter our fears by saying that words are not the same as actions? Words fuel action. Words incite action. If a person in a position of power has expressed that women are pigs, that Muslims should be sent out of our country, that disabled people are to be used as a joke, others in our country hear that message loud and clear. Even in the impossible scenario that the person speaking those words weren’t to ever act on them, those words have already acted as a catalyst for the actions of millions of others. Words are powerful.

It is also possible that those who say we are overreacting are afraid of what our reactions might mean, what they might do. This is where the truth lives, because often sadness and fear mix together to form a rage rising up inside of us — a rage that we can harness, collectively, to demand better.

“Is there a place for collective anger going forward? Or should we try to put that aside to keep calm and loving?”

Looking back on the past 10 years of my activism, I can say that my biggest approach has always one of “keeping calm and loving.” I have long been the kind of person who doesn’t want others to have to feel uncomfortable, and who holds tight to common ground as a bridge between differences. When my wife and I got engaged, I wrote my religious extended family members a letter that essentially helped them to feel less guilt and shame about making the choice to not attend my wedding. I felt our presence would help them slowly come to understand us as people, instead of words, stereotypes, or worse: people who did not deserve the same rights as they did.

I advised the young people who would ask me about similar situations to take care of themselves, and to — as much as they were able — also have patience and love for those in their life who could not yet understand.

This week, everything changed.

I still believe in the value of love.

I still believe in the value of patience.

I still believe in the value of kindness.

However, I no longer believe in keeping calm when others, either overtly or otherwise, participate in a process that ultimately leads to inequality. This was what I was doing, for all of those years; I valued the comfort of my loved ones more than I valued myself and more than I valued marginalized communities, and I will not do it any longer.

Yes, there is a place — an incredibly important place — for constructive anger.

Many of us have been angry about the rise in Islamophobia that began with 9/11. Many of us have been angry about the pervasive racism that we see reflected all around us in this country. Many of us have been angry about transphobia and homophobia — both nuanced and direct. However, for too long, too many of us have valued the comfort of others over giving voice to that anger.

"It is okay — in fact it is critical — to put your physical, emotional, and mental safety first."

We cannot value the comfort of others any longer if the price is inequality.

First, I would like to tell you what I plan to do with my own anger: I will march in the streets. I will put out messages of love and light to those who are struggling, and messages of bold and uncensored truth to those who still have yet to see it. I will raise up the voices of trans, black, and brown people, Muslims, immigrants, and those with disabilities above my own. I will work to educate white people as a fellow white person, rather than leaving that burden to people of color. I will demand better for the LGBTQ young people of this country, and this world. I will keep my eyes open to the many ways that these marginalized identities overlap and intersect in our country, and never move forward as though this is a fight for just one group. I will donate as much as I am able to organizations like Planned Parenthood, the ACLU, NAACP, and the dozens of local LGBTQ youth centers and organizations that light our path forward in this fight.

I will put these efforts ahead of ensuring the comfort of my loved ones, because right now queer and trans communities, black and brown communities, and Muslim and immigrant communities need me more.

These are all places in which you, too, can feed your own anger, and the collective anger you are feeling as LGBTQ young people. It is also incredibly important to stress the importance of staying safe. Please always be aware of your surroundings, always be aware of yourself, and please know that it is okay — in fact it is critical — to put your physical, emotional, and mental safety first.

If you cannot safely march, if you cannot safely be vocal, you can still work to take care of your important, valid, cherished self. Read books. Read all the books. If you cannot purchase them, look to your local library, or look online. Here is an ongoing list of books that we talked about during our livestream; use that as a start and then add to the list with your own ideas and suggestions. If you have LGBTQ friends who are local, spend more time with them now than ever before. If you do not (or even if you do), spend more time with online communities of LGBTQ people.

Bit by bit, pull what is good toward you, and learn every facet of your strength, every nuance of your weakness. Keep advocacy and outreach resources close to you and share them with your friends should they need someone to lean on. Keep each other strong, build each other up, and love each other more fiercely than you ever have before.

Know that those of us who can will never stop fighting for you.