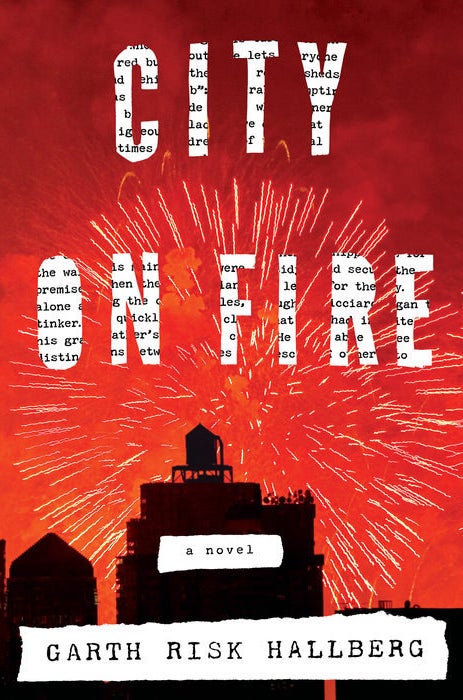

City on Fire is one of the year’s biggest books — and I mean that literally. Garth Risk Hallberg’s novel clocks in at a massive 944 pages long, spanning nine characters wrestling with their sense of place in the decaying cityscape of late-‘70s Manhattan. It is an ambitious and confident novel, particularly for a debut author, that summons the universality of aspirations, expectations, and loneliness, but grounds them in a specific time and place.

When I spoke with Hallberg earlier this year at BookExpo America in May, he was amid a publishing industry–focused publicity blitz. The stacks of advanced copies of City on Fire were given away quickly to conference attendees, along with cute promotional City on Fire matchbooks, beneath a giant City on Fire banner. But can a novel hyped heavily within an industry break out as a mainstream success?

Hallberg didn’t seem worried. Like his novel, he came across as self-assured — not necessarily about the book’s commercial potential, but about the work he had created. He talked at length about City on Fire’s cultural inspirations (Harriet the Spy, punk rock, Billy Joel), actively avoiding the internet, and the eerie parallels between New York during the “bad old days” of the ‘70s and the decade following 9/11.

Kevin Nguyen: What inspired the book?

Garth Risk Hallberg: The big, vague answer to that question is that I’ve always been in love with the city, ever since I was a little kid first entering it through Harriet the Spy and Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing and Stuart Little and all these iconic New York books. Later, as a teenager, I was kind of a punk-rock kid, and there’s no more meaningful time or place in the history of punk rock — or at least I like to think so, anyway — than New York in the mid-‘70s. In some ways it must’ve been gestating for a long time.

The more approximate inspiration for the book was kind of the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in 2001. This place I’d dreamed about for so many years and that I’d spent half my life trying to get to suddenly seemed on the verge of destruction. How terrifying that was, and how sad that was, and, in some strange way, how clarifying that was. When something is at risk or in danger or about to be lost, those are the moments you start to realize how much it means to you.

When something is at risk or in danger or about to be lost, those are the moments you start to realize how much it means to you.

One thing I remember about that time, amid all the grieving and all the fear and all the great sense of loss, [is that] it was also one of the times in my historical moment when I remember people collectively — as a country, as cities, as groups of friends, as families — not just thinking about but openly discussing, Why are we here? What do I really want to do with my life? What kind of society are we going to have in the future? What’s the world going to look like?

That time of possibility, for me, was 2001, 2002, 2003. I was living in Washington, D.C., then, but I was making trips up to New York then and I just needed to make contact with my friends who were living here.

I was listening to — weirdly enough — a Billy Joel song on an early-generation iPod about the blackout of ‘77 and I was on a bus in New Jersey looking out across the Meadowlands at the skyline — the now altered skyline — and listening to this song about the blackout and danger and fear and terror and panic and disorder and chaos and hope and possibility and meaning and change and connection, and that’s the historical moment of the song. And I thought, Oh my god, we’re living through that moment again.

KN: Have you been working on the book since 2001, 2002?

GRH: I got off that bus and I went to Union Square and I sat down and wrote a page. It was within 30 seconds, while the song was playing, I thought, There’s gonna be this book and all these characters. The characters were coming and all these phrases were coming, including the scale of it. I sat down an hour after just to get down some notes, and I wrote this scene and the scale of it scared me so much. I was 25 and I thought, I don’t have the chops to write this. This is crazy. And I closed the notebook and I put it in a drawer and thought I would maybe come back to it 10 years when I’m a better writer.

Four years later was actually when I came back to it. I couldn’t stay away from it any longer. Four years is right as the financial crisis was starting to happen, and one of the other weird parallels between our time and that time is that there’s this massive fiscal crisis in New York in 1975, which in many ways set the stage for the iconic scenes of disorder and decay that came out of the blackout. The city went into technical bankruptcy and was bailed out.

I remember going into an art exhibition in Chelsea in the fall of 2008 and walking in and everything is normal and walking out and my friend checks his phone and says, Oh my god, the stock markets are crashing; the world economy is going to come to a halt. Another near-death experience, and that happened in ‘75 too. That was the time I picked back up writing it.

KN: The origins of City on Fire are starting to become mythical. Here’s this relatively unknown debut novelist. The rumor was that the original first draft was 1,200 pages; you kept it in a drawer for a long time. Are you worried that the expectations will overshadow the reception?

Reading isn’t about managing expectations.

GRH: That’s just not really my problem. That’s somebody else’s problem at this point.

Reading isn’t about managing expectations. In certain ways, writing is. You’re trying to send signals early in a book about what might be coming later, but I think worrying about the kind of chatter around a book is something I try and stay as far away from when I’m reading.

KN: Is it hard to keep that noise out of your life?

GRH: Yes, super deliberate. Fingers crossed, I would like to be able to preserve the kind of internal quiet. The writing that feels the best to me, I experience sometimes, is a kind of weirdly deep listening — like it feels like if you just listen hard enough the next sentence will tell you what it needs to be. That requires making these deliberate choices to not lose track of the next sentence because you’re like, Is something out there in internet world? Definitely something is happening out there in internet world at any given moment, but the likelihood that it’s something that can’t wait until that evening for you to find out about it is very small.

The writing that feels the best to me, I experience sometimes, is a kind of weirdly deep listening.

KN: Have you done interviews since the book sold?

GRH: I guess I have done a couple of interviews, and doing some more today. It’s wild. It’s exciting to see the book in people’s hands. It’s crazy to imagine that people want to dive into something so big. I know when I’m reading something I love I never want it to end, so I’ve always gravitated toward these big world-building [novels] — Lord of the Rings, Bleak House, Lonesome Dove, Middlemarch — I’ve always loved those worlds you could just dive into.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

***

Kevin Nguyen is the editorial director of Google Play Books. He has written for Grantland, The Paris Review, The New Republic, and elsewhere.