Scientists have found evidence for hydrothermal activity in an ocean on one of Saturn's moons, making them even more excited about the possibility that it hosts life. Their results are published in the journal Science today.

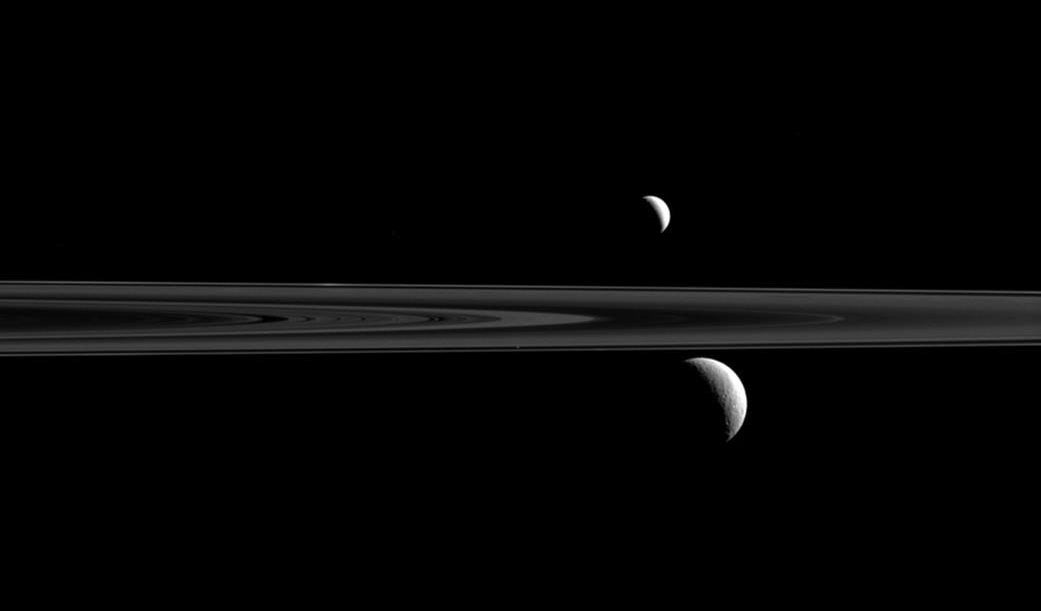

Enceladus, Saturn's sixth largest moon, has got four "tiger stripes" near its south pole, from which ice and water erupt.

Since NASA's Cassini mission discovered the stripes, and found evidence for a subsurface ocean underneath them, scientists have cautiously wondered whether something even more exciting than the ocean itself was lurking underneath the surface of the moon.

Cassini, in a flyby of Enceladus, sampled water coming from the plumes, and the study out today announces that, in some of the samples, scientists have found molecular hydrogen, or H2.

"This data provides the strongest evidence yet for hydrothermal activity below the surface of Enceladus at the seafloor," Christopher Glein, an author on the paper and geochemist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, told BuzzFeed News.

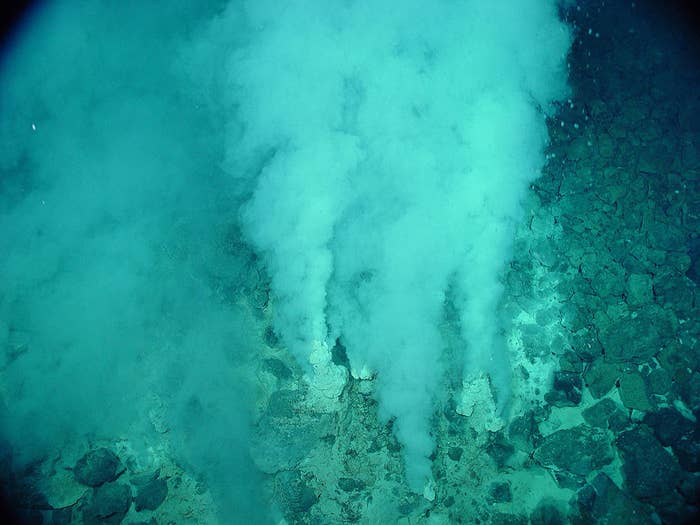

In Earth's oceans, certain kinds of life cluster around these hydrothermal vents, using chemicals as their basic food source, just like plants on the surface of Earth use sunlight.

"People have dived down to the bottom of the seafloor and taken samples, and you see all this hydrogen spewing out of these systems and the microbes down there are eating the hydrogen," said Glein.

"Some of the most ancient microbe life on Earth feeds itself on the energy released by reacting hydrogen with carbon dioxide," Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiologist and professor of science communication at the University of Westminster, told BuzzFeed News. "So we now realise that not only does Enceladus provide a habitat for life, but also chemical energy to fuel an ecosystem."

The newly discovered hydrogen lets scientists investigate what's called the "chemical disequilibrium" of Enceladus's ocean, a way of measuring how much energy might be available to any underwater life there. Glein compares this to a "calorie count".

"If something were alive in Enceladus's ocean, we now know how much energy would be obtained if that bug or critter were to eat the hydrogen as a fuel source for obtaining energy," he says. "That's very exciting."

Before concluding that the hydrogen is a sign of hydrothermal activity, Glein and his colleagues had to rule out several other possible explanations. Gas giants like Jupiter contain a lot of hydrogen, for example, but "we certainly don't think Jupiter has hydrothermal vents," he said.

"There were probably about five or six alternatives to the hydrothermal [explanation], but all of them seem to show an inconsistency with the data. The hydrothermal one best matches the data," he said.

"There's quite a chain of reasoning needed to eliminate other sources of H2, although that reasoning sounds pretty solid to me," Caleb Scharf, director of astrobiology at Columbia University in New York, told BuzzFeed News. "[Hydrothermal activity] certainly looks like the simplest explanation."

This new discovery slots nicely into a mounting pile of evidence that Enceladus is a good place to look for alien life in the solar system.

Before the Cassini mission, which reached Saturn in 2004 and discovered the "tiger stripes" and moons in 2005 followed by the first evidence for liquid water under the moon's surface in 2006, little was known about its habitability. But Cassini will meet a sticky end later this year.

"The risk is that once its fuel runs out and we lose control, in years to come it may crash into Enceladus and potentially contaminate the icy moon with earthly bacteria. So in the interests of ‘planetary protection’, Cassini will be deliberately plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere to burn up and be destroyed," said Dartnell.

"In many ways, Cassini’s own spectacular discoveries have ensured the necessity for its fiery demise into the upper cloud decks of Saturn."

One thing that might dampen enthusiasm for Enceladus's ocean hosting life is a relatively new suggestion that Saturn's moons have not been around for as long as the rest of the solar system. "We don't really know how long it takes for life to develop, but certainly it would seem less favourable if you only have 100 million years versus 4,000 million years," says Glein.

The only way to find out either way, though, is to go back there. And now that Cassini has done its last flyby of Enceladus, scientists are beginning to think of future missions to the icy moon.

"The next step we're thinking about it searching for direct signs of life, Cassini was not designed to do that," said Glein. "We had no idea the plume was even in existence. So all the data from Enceladus is kind of a bonus."

"What we're going to need to do next is send a new mission. Somebody is going to need to go back there," he said.

Any new mission to Enceladus will need to look for direct signs of life, such as amino acids – the building blocks of proteins – and for other geochemical signatures in the plumes.

Glein himself is part of a proposal for a mission called Enceladus Life Finder, part of NASA's new frontiers programme. Enceladus Life Finder would contain specially designed instruments for spotting geochemical signs of life in the moon's plumes.

But looking more closely at the plumes is just one way to find evidence of life.

"I also think at this point we have to think about direct sampling – grabbing plume material right at the surface, or even trying for an interior sample," said Scharf. "A bucket of Enceladus ocean water would be like gold."

"Given all that we now know about Enceladus, it's faintly ludicrous that we're paying so much attention to Mars in the search for life," he added. "At this point Enceladus is laying out a splendid buffet and we're reaching for the burnt toast."