"Black women are angry/mean/difficult." This widely accepted misconception is used to invalidate our feelings while validating the source that has caused us to feel this way. "You really need to calm down," they tell us, and "I just feel like it's not that deep/you're overreacting."

"Black women (especially darker skinnned black women) are generally unattractive/ugly." This is another widely accepted misconception that pushes the agenda that European beauty is the only valid standard. "She's too dark for my taste," they bark, and "I usually don't date black women, but you're different." And the WORST thing you could ever say to a black woman: "You're really pretty for a black girl."

As a collective we’ve heard it all before, right? We’ve heard it from people that don’t know us. We’ve heard it from people who do know us. We’ve heard it from within our own community and from our own men. As black women in America, we’ve learned from a young age that we are held to much higher standards and expectations than non-black women (and generally anybody). It is because of these ridiculous standards and misconceptions about us that we feel as though our “best” still manages to come up short in comparison to someone else’s “worst” or “average”.

These misconceptions about us not only lead us to question our self-worth, but it perpetuates implicit racial bias in other areas of our lives such as the workplace, the dating scene (as well as our platonic relationships), and more severely at the hospital.

Not to mention, with the media and tv/film industry constantly highlighting these stereotypes, it further skews others’ perception of us (never as individuals but always as a collective) while validating the negative preexisting beliefs they may have already had.

For example, producer and actor (amongst other things in the tv/film industry) Tyler Perry, is most famous for his character Madea(who he plays), who is an older black woman known for being loud, rambunctious, and risque. While this character is meant to be funny, when examined on a grander scale, "she" becomes pretty offensive when you realize how big of an influence Perry's movies, and Madea in particular, have on people outside of the black community. In short: it's all fun and games when it's you and your community enjoying the content made by them and targeted for them until other people start butting in on the jokes, unable to differentiate what is a stereotype from what is real. I believe it is for these reasons that Tyler Perry has decided to no longer bring this character back to life.

This false narrative(that black women are loud/angry/mean) makes me feel as though my emotions have limitations; like my ability to "remain calm" even in the most troubling of situations seems to be what works best for everyone so it's just what I should do.

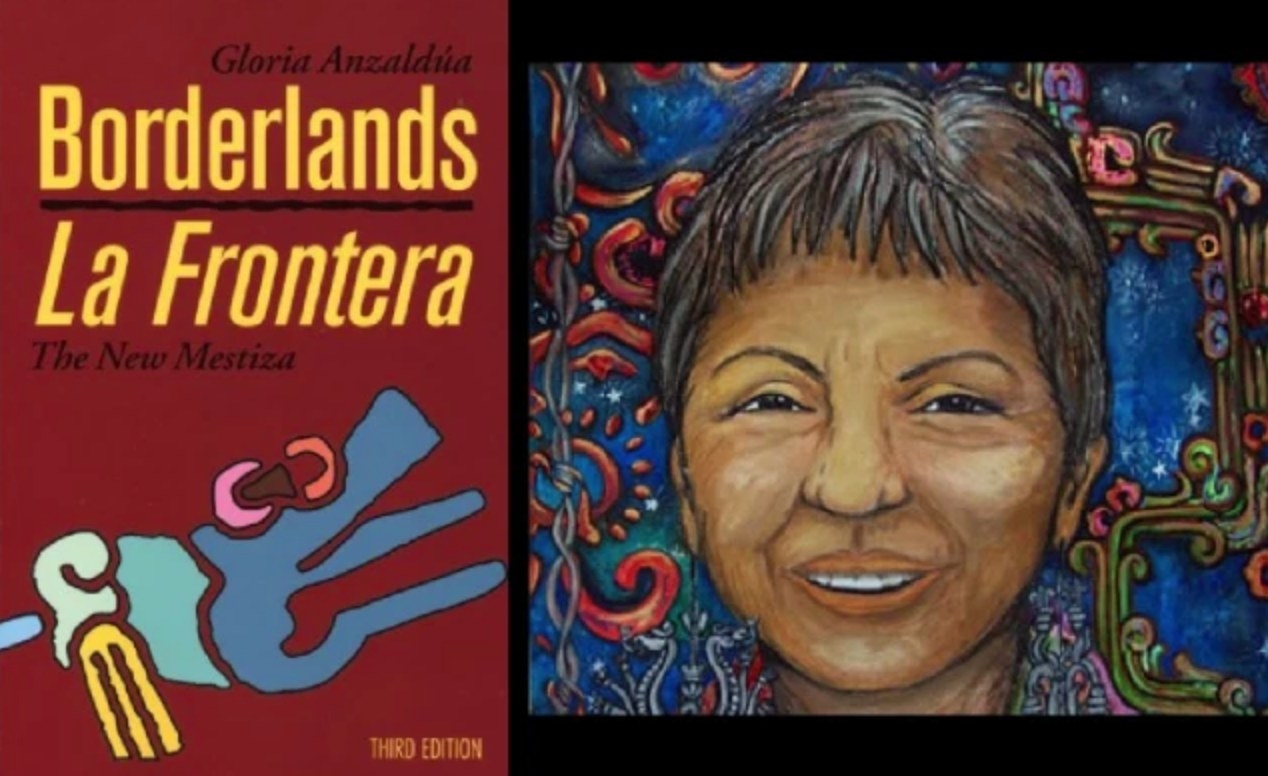

As a young girl I was taught from a very young age to hold my tongue and not “act out of character” because I should expect to face more severe repercussions(because I am black of course) for “speaking up” or “having an attitude” with the wrong individual at the wrong time. In my case(or maybe ours), “acting out of character” serves as a double entendre because similar to scholar Gloria Anzaldúa, I was my authentic self at home. I spoke freely and didn’t second guess my words before saying them. However, in the face of other people (usually older white people) I was smiling more than normal, always going out of my way to be very polite and friendly, and choosing my words very carefully.

Anzaldúa, in her book Borderland/La Frontera, recalls speaking in Spanish only while at home and with her natural accent. This is because her home was a refuge from the more socially accepted English she had to speak while at school. Not only was her language a target for scrutiny, but her accent was looked down upon as well. She revealed that she took two English classes in grade school because of this. One class was for the English language and the other was for English dialect (or for better words erasure of her accent).

Me and Anzaldúa. Two women from two very different generations yet experiencing the same oppression: the silencing of our voices.

My experience with coming to voice, however, has been a long and ongoing spiritual journey, one which I am grateful to be on at such a young age and with the full understanding that the world is my oyster. I attended Clark Atlanta University, a historically black college university in Atlanta, Georgia where I was surrounded by black scholars, black educators and immersed in rich black culture and history. Writer Richard Rodriguez knows all too well how the way you feel about yourself begins to change when you see people that look like you embrace themselves so unforgivingly and this is exactly what happened with me.