The Australian Federal Police have reported that, for the first time on record back to 2006, they handed over Australian metadata to China.

The revelation comes from the annual Attorney-General's Department report on the operation of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act that gives Australian law enforcement agencies powers to access the call records and other metadata of every Australian telephone and internet account without a warrant.

Australian has signed a mutual assistance treaty with China that obliges Australia to hand over "documents, records and articles of evidence" in relation to criminal matters. Similar treaties all over the world help law enforcement authorities share information to help catch criminals in their own country, but it appears that during the 2015-2016 financial year was the first time Australia had ever reported that China had been provided metadata under this scheme.

A spokesperson for attorney-general George Brandis denied that this was the first time data had been handed over (a previous disclosure had been made to Hong Kong), and said that international cooperation with foreign law enforcement agencies was vital, but that there were safeguards in place to ensure Australia was still in compliance with human rights obligations when handing over the data.

"Given the global nature of serious transnational and organised crime, effective international cooperation is critical. Any cooperation, including with China, is subject to safeguards to ensure compliance with our international human rights obligations."

The spokesperson indicated that the government had only been required to report on the disclosures to foreign law enforcement authorities since 2012, but he provided no detail on how often data had been shared with China before Australia was required to report it publicly.

There were a total of 23 disclosures of information from the Australian Federal Police to enforcement agencies in other countries in that year. In addition to China, Australia handed over metadata to Taiwan, Hong Kong, Serbia, Switzerland, Solomon Islands, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Zimbabwe, Argentina, Slovenia, Canada, Germany, Singapore, Indonesia, the United States of America, Papua New Guinea, the Republic of Ireland, Netherlands, Spain, and France.

The release of the report from the Attorney-General's Department is around nine months later than it is normally released to the public, and is the first insight into the operation of the law under the new mandatory data retention scheme that came into effect in late 2015.

In 2015, the Coalition government passed new laws requiring Australia's telephone and internet service providers to retain so-called "metadata" created by their customers for a period. This includes customer information such as the names, physical addresses, and other data like who a person called, and when, how long the call went for, where they were located at the time of the call, and what unique IP address they were assigned when accessing the internet at a certain point in time.

For a handy reminder, here's that Walkley Award-winning interview with attorney-general George Brandis on what is and isn't metadata.

View this video on YouTube

Companies had been keeping this data in the past, and were required to hand it over to government agencies without those agencies first getting a warrant, but the companies didn't need to keep the data for their own business purposes for as long as the government wanted, and were deleting it. Law enforcement complained to Brandis about it, and so legislation was brought about to force them to keep it, just in case.

The justification for the new law was that companies like Telstra, Optus, and TPG were required to keep this data to help law enforcement agencies investigate serious crimes including terrorism, child sex abuse, and organised crime. In order to get the support of Labor to pass the legislation, the government also included some new provisions, including reducing the number of agencies that can access the data, and a "journalist information warrant" that law enforcement must get in secret, and without the journalist's knowledge before they're allowed to access the metadata of that journalist for the purpose of investigating a leak.

Each year the Attorney-General's Department reports back to the public on how many times all agencies accessed this data. The first report for the 2015-2016 financial year should have been released about November last year, but the government held off on releasing it for months, claiming several times when asked by BuzzFeed News that it needed more time for the changes that came with the new law.

Months and months passed.

Then on Monday, finally, the report was tabled in parliament and released to the public.

So what have we learned about how the new law is working?

The number of times agencies sought metadata went down.

The above table is just for law enforcement agencies, and doesn't include all the agencies that were cut off once the new law was brought into effect, but this alone shows that there was a slight reduction in the number of requests for accessing metadata, down to 325,807 authorisations for metadata, versus 353,272 in the previous financial year.

This is probably more to do with the cases, rather than anything to do with the law changing, but is unusual considering the trend over the past few years has been for more requests for metadata.

Of these requests, 57,166 were related to illicit drug offences, 25,245 requests were for homicide offences, and 4,454 requests were made to assist terrorism investigations.

Journalists were spied on. But not from who you'd expect.

You'd expect that the Australian Federal Police as the national law enforcement agency would be the most likely to be all up in journalist's metadata chasing those leaks from offshore detention or those embarrassing political leaks, but in the first year, at least, the AFP didn't get any journalist warrants.

The report reveals that just one agency - the Western Australia Police - sought and received any warrants to chase the leak to a journalist. There were two warrants given to WA police to access data 33 times in that year.

Paul Murphy, CEO of the journalist union, the Media, Entertainment, and Arts Alliance, told BuzzFeed News that it was "disturbing" to learn that 33 authorisations for a journalist's metadata were made in the first year. It is not known what the story was, and the journalist themselves have no idea that their metadata was accessed because it is against the law to disclose almost anything about the warrant.

"This Journalist Information Warrant scheme operates in secret. Journalists and media organisations are never informed a warrant has been applied for, let alone granted," Murphy said. "It completely subverts both the public interest and press freedom and should be scrapped."

The AFP DID access a journalist's metadata in searching for a leaker earlier this year, but oops, forgot to get a warrant. That one will likely be detailed in the 2016-2017 annual report out...sometime.. in the next year.

Mandatory data retention is expensive AF, and taxpayers are picking up the tab.

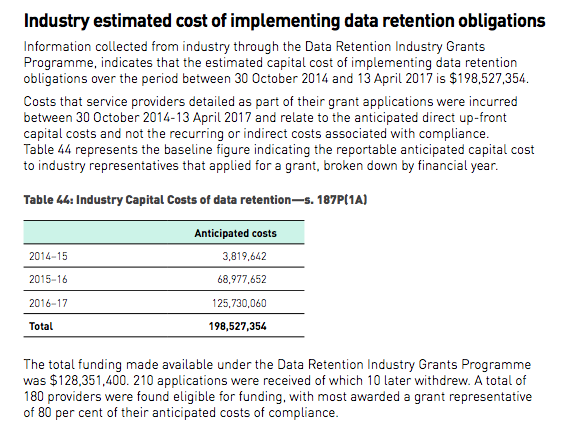

As an olive branch to the telecommunications companies for forcing them to comply with the new data retention laws, the government offered up $128 million in grants to the companies to build their systems to store the data and operate under the new scheme.

The report reveals that the costs as of April this year for the telecommunications companies has been $198.5 million, but $128.3 million of that was paid for by taxpayers. 200 grants were made to telecommunications companies small and large from the federal government in the past couple of years.