During the last 10 years of her life, Anna Jarvis, the founder of Mother’s Day, lived with her blind sister, Lillian, in a three-story redbrick house in North Philadelphia. In the late 1930s and early ’40s, a “Warning — Stay Away” sign greeted visitors, and Jarvis answered the door only if a visitor used a secret knock or a certain number of doorbell rings.

Heavy curtains hid a broken window and darkened a Victorian parlor filled with horsehair furniture and clutter from decades of Mother’s Day proclamations, letters, and news clippings. On the wall was a large portrait of her mother, Ann Reeves Jarvis, surrounded by holly wreaths. In a Reader’s Digest story from 1960, a reporter recounts visiting her on one of the last Mother’s Days in her Philadelphia home: “She told me, with terrible bitterness, that she was sorry she ever started Mother’s Day.”

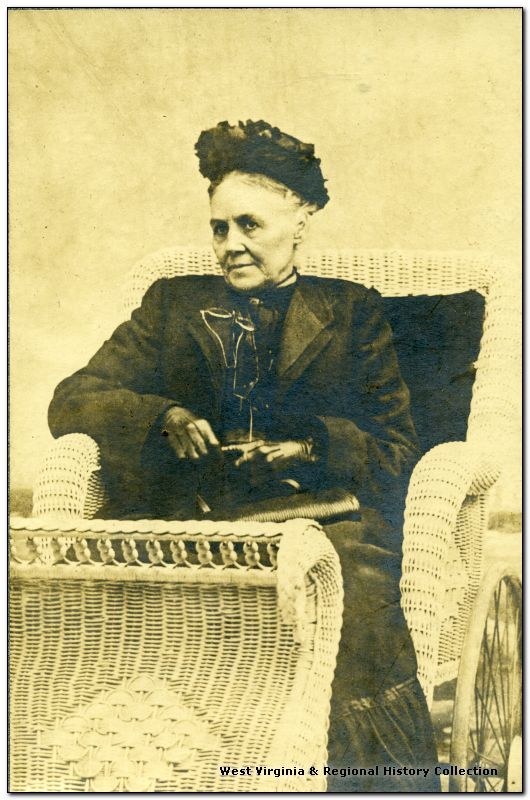

In her younger days, Jarvis was described as attractive and intelligent. When a doll was to be made in her likeness in 1933, the instructions given from her organization, Mother’s Day Inc., were for a visage that was “fair, with blue eyes and light brown hair.” She stood 5-foot-5 and preferred blue, size 40 costume gowns with an open neck, pearl necklaces, and blue hats atop her untamed hair. In photographs Jarvis conveys confidence, but even early on, there’s a weariness in her eyes.

Later in life, the New York Times described Jarvis as “worn and fragile” and “a frail little spinster who resembles Whistler’s Mother.” Newsweek said she “seldom smiled.” In amateur historian Howard Wolfe’s 1962 book Behold Thy Mother, Jarvis’ mother was said to be “the most loving and lovable teacher, with the sweetest voice and pleasing smile we have ever known,” but that Jarvis herself “lacked much of the graciousness with which her mother was most abundantly blessed.”

In late 1943, Jarvis' friends and business associates became aware of her declining health and had her committed to a sanitarium in West Chester, Pennsylvania. (Lillian stayed behind in the house and was found dead a couple of months later.) Wolfe said Jarvis displayed a particular letter on her bedroom wall at the sanitarium. “I am 6 years old and I love my mother very much,” the note read. “I am sending this to you because you started Mother’s Day.” Sewn to the letter was a $1 bill.

Jarvis died in 1948 — blind, emaciated, broke, and surrounded by strangers. She never married and never became a mother herself. “Her last days were embittered almost beyond comprehension,” Wolfe wrote.

Jarvis’ crusade to create a holiday to honor mothers in the early 20th century was only the beginning. As the day grew in popularity, she committed the next 40 years of her life to protecting and defending it from anyone who tried to co-opt Mother’s Day for their own causes and financial gain. Yet her efforts led to her own financial and emotional ruin — and were often portrayed as excessive, gaining her a reputation as an eccentric. Still, Jarvis’ battles with the candy, floral, and greeting card industries anticipated the commercialism that’s now inseparable from modern-day Mother’s Day.

On May 28, 1876, Ann Reeves Jarvis was teaching her Sunday school class, which included daughter Anna Jarvis, then 12, about notable mothers in the Bible. She closed the lesson with a prayer: “I hope and pray that someone, sometime, will found a memorial mother’s day commemorating her for the matchless service she renders to humanity in every field of life. She is entitled to it,” Reeves Jarvis prayed.

Anna paid particular attention to the prayer that day. Perhaps it was the first time she realized what a thankless, sacrificial endeavor motherhood could be. As she recalled years later, “This heartrending, agonizing prayer burned its way into my mind and heart so deeply, and it never ceased to burn.”

Anna’s mother spent much of her life championing women’s causes through work clubs that helped improve health and sanitary conditions in West Virginia, including providing assistance to mothers with tuberculosis. After the Civil War, Reeves Jarvis also created a Mothers’ Friendship Day to ease tensions and promote peace among the war-torn republic. She died in 1905, but not before burying eight or nine of her own children (genealogies vary).

According to Anna Jarvis’ brother Claude, “My sister Lillian and myself were standing beside the open grave on the side. As the bishop said, ‘Dust to dust, ashes to ashes,’ Anna broke out in a heartbreaking cry and said, ‘Mother, that prayer made in our little church in Grafton calling for someone, somewhere, sometime to found a memorial to mother’s day — the time and place is here, and the someone is your daughter. And by the grace of God, you shall have your Mother’s Day.’”

Anna Jarvis claimed she went straight from the gravesite to her home in Philadelphia, where she had moved in the 1890s, to start planning for Mother’s Day. Her campaign didn’t begin in earnest until 1907, but over the next few years, Jarvis wrote thousands of letters to any prominent figure who could wield influence: President Teddy Roosevelt, of course, and 1908 presidential hopeful William Jennings Bryan, but also Mark Twain and former Postmaster General John Wanamaker. The campaign quickly gained steam, even though some — particularly women — ridiculed her idea, and the Senate initially rejected the Mother’s Day resolution in 1908. Wanamaker was one of the first to jump on board in support of her. “It seems possible if we give our hearts to this loving service, it will become one of the most beautiful days of our lives,” he wrote. Twain’s commendation was printed in newspapers in Philadelphia and New York, and Bryan said he was “heartily in sympathy with the movement.”

On May 10, 1908, the first official Mother’s Day services were held in Grafton at Andrews Church and in Philadelphia, where Jarvis spoke for 70 minutes at the Wanamaker Store Auditorium. The venue seated 5,000, but 15,000 tried to gain admission. Wolfe wrote that Russell Conwell, founder of Temple University, heaped praise on Jarvis after her address. “You are a convincing orator, a brilliant thinker,” he said. “You will be able to obtain what you want. Your Mother’s Day idea will honor you through ages to come.”

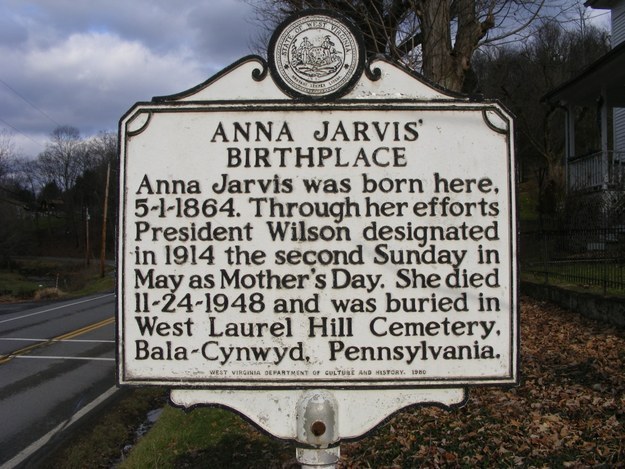

Most states held Mother’s Day celebrations over the next few years, and Jarvis, who proved an adept publicist, annually requested official Mother’s Day proclamations from state governors, who implored their citizens to observe the day and wear a white carnation. “Next to the name of God,” Kansas Gov. Walter Stubbs proclaimed, “the sweetest word in the English tongue is ‘mother.’” With virtually the entire United States celebrating Mother’s Day state by state, Woodrow Wilson signed legislation designating the second Sunday in May a national holiday in 1914.

Jarvis declared the white carnation the official flower of Mother’s Day, and she urged sons and daughters to visit their mothers or, at the very least, to write home on Mother’s Day. “Live this day as your mother would have you live it,” Jarvis instructed in her letters. Her vision for the day was domestic — focusing on a mother’s role within the home — and highly sentimental. It was to be celebrated “in honor of the best mother who ever lived — your own.”

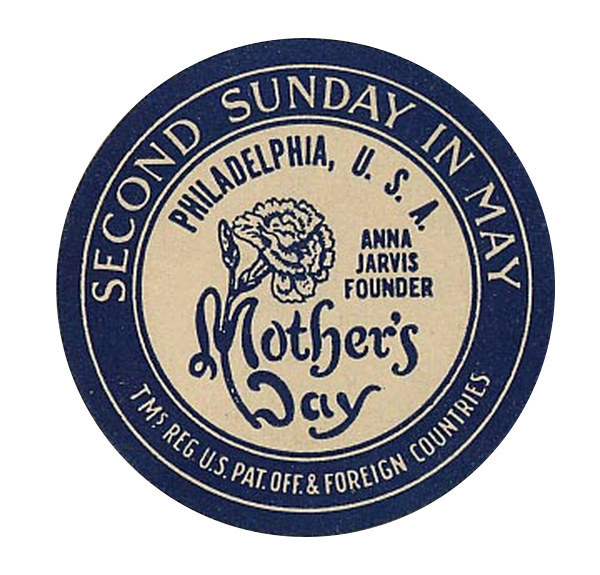

Founding Mother’s Day and fulfilling her mother’s wish was Jarvis’ crowning achievement, and continued to be her all-consuming, singular purpose in life well after the day was officially established in 1914. It wasn’t enough for her to be the originator of Mother’s Day. Jarvis wanted to own it, and she didn’t want any outside forces corrupting her vision of what the day should be. She incorporated herself as the Mother’s Day International Association, copyrighted her own photograph, and trademarked the Mother’s Day Seal with a drawing of a carnation and the words “Mother’s Day” (always singular possessive to distinguish from “Mothers’ Day” impostors), “Second Sunday in May,” and, of course, “Anna Jarvis Founder.”

Each year Jarvis put together an official Mother’s Day program that included a personal message and suggested music and readings to be used at services and celebrations. All of this required so much time that she quit her job with a life insurance company, where she had been the first female literary and advertising editor, to work on Mother’s Day full-time. She spent the rest of her life promoting her founding vision for the day while also fighting the floral, confectionary, and greeting card industries (“schemers” and “profiteers,” as she called them) who were making money off her holiday.

In 1923, for example, Jarvis crashed the convention of the Associated Retail Confectioners in Philadelphia, accusing them of “gouging the public.” “I want to tell you that you are using a beautiful idea as a means of profiteering,” she told the confectioners, according to a New York Times story. “As the founder of Mother’s Day, I demand that it cease … Mother’s Day was not intended to be a source of commercial profit.”

Nonprofits were also fair game: In 1925, Jarvis was charged with disorderly conduct at a convention of the American War Mothers, which sold carnations to raise funds for servicemen and their families. “It was alleged that Miss Jarvis appeared without invitation at the convention of War Mothers and protested against the adoption of the carnation as the emblem for that organization,” the Times reported.

She even turned on Wanamaker, her biggest champion early on. In one news clipping, a former assistant to Jarvis recounted a story in which Jarvis ordered a salad in the Wanamaker's tea room only to dump it on the floor because it was designated a “Mother’s Day Salad.” In a letter, she accused Wanamaker of trying to crush her movement.

At one time, Jarvis reportedly had 33 Mother’s Day–related lawsuits pending. No one was immune from her stranglehold on the holiday — not even the president’s wife. Eleanor Roosevelt was the honorary chair of the Golden Rule Foundation, which sponsored a fund for needy mothers and their children. Jarvis claimed the organization was trespassing on her cause and commercializing the day, and threatened to sue.

“I think she misunderstands us,” the first lady told the Times in March 1931. “She wanted Mothers’ Day observed. We want it observed, are working for its observance and are really aiding her.”

Early on, Jarvis endorsed boycotts of florists who raised the price of carnations every May. In 1908, she bought 500 carnations for half a penny each; by 1912, they were 15 cents apiece. Jarvis told her cousin in a letter that “the florists are the leaders in causing me so much trouble” — so much trouble that Jarvis eventually rescinded the carnation as the official emblem, replacing it with a Mother’s Day International Association button. “This will do away with profiteering tradesmen and carnation peddlers seeking their own profit through Mother’s Day,” she wrote.

But, of course, the button and lawsuits and protests and boycotts didn’t do away with any of that. Try as she might, Jarvis couldn’t stop Mother’s Day from becoming a cash cow. One stroll through the grocery store in the first two weeks of May proves as much. Last year the National Retail Federation estimated Americans would spend about $20 billion on Mother’s Day gifts; 80% will buy greeting cards, and 66% will buy flowers.

One hundred and one years after Mother’s Day became a national holiday, how do we explain Jarvis’ life and legacy? Was she truly the delusional, “frail little spinster” news reports described? Defending a holiday against commercialization is one thing — but why fight, repeatedly, with beloved charities?

No one knows the story of Anna Jarvis better than Katharine Antolini, a professor of history and gender studies at West Virginia Wesleyan College. She lives about 45 minutes from Grafton, where the church Jarvis and her mother attended is now the International Mother’s Day Shrine: a historic but unassuming redbrick building with a white steeple that sits on Main Street and looks like countless other small-town churches of the era.

“They’re lovely people, but none of them are archivists or historians,” she says of the shrine’s volunteers. “All these great, nearly 100-year-old documents were sitting in a box on the floor in the kitchen. I spent the summer [of 2004] archiving the documents, and there was this one letter. It was seven pages long, typed. [Jarvis] wrote it to her cousin in 1933, and she’s ranting about all these people.”

That letter, along with other documents that had been hidden from historians in a box for decades, piqued Antolini’s interest. What began as an archival reorganization project eventually became Antolini’s dissertation and, later, a book. Antolini doesn’t shy away from Jarvis’ eccentricities, but she also sets out to explain her behavior.

“I think a lot of it was ego-driven — wanting to be ‘Anna Jarvis, founder of Mother’s Day,’” Antolini says. “She would constantly sign letters that way. It was such a big part of her identity and her adult life, so any kind of threat to take that away from her is what terrified her.”

But Jarvis was also an unmarried, childless, opinionated, economically independent woman living in the first half of the 20th century. “Sometimes calling her crazy was a way to dismiss a strong woman who had a vision and a movement and was determined to see it through her way,” Antolini says. “Those are the kind of qualities that you would have respected in a man in the early 20th century — not so much in a woman. To be willing to sue and to stand up to the elites of New York City and challenge Eleanor Roosevelt…in a lot of ways, she was fearless.”

Read through that lens, the media’s constant reference to Jarvis as a spinster becomes a way to frame her as damaged or undesirable and to undermine her accomplishments. Because of Jarvis' notoriety, generating copy about her — good, bad, embellished — was part of the publicity apparatus of the times.

“Everything you read in Time or Newsweek — how much of it really did happen, and how much of it was blown up to make a good story and to make this strong woman seem crazy?” Antolini says. Jarvis fought back against the media’s characterizations of her — in 1938, she sent out a press release saying the way she was depicted in a Time story was defamatory and libelous — yet her own, ongoing Mother’s Day publicity campaign ensured she’d stay in the news.

Even today, it’s difficult to separate mythology from fact. Take one of Jarvis’ best-known quotes, which is cited in nearly every online article about her: “A printed card means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world.” Neither Antolini nor I came across this quote in documents. It doesn’t sound unlike something Jarvis would say, but the source is unknown, if it exists at all.

By all accounts, Jarvis stayed true to her claim of never profiting financially from the holiday she founded. She was committed to protecting the purity of Mother’s Day, and she believed money sullied that purity. Antolini says Jarvis didn’t trust charities’ allocation of funds, but she especially hated the notion that charitable causes were transforming Mother’s Day into an occasion where mothers were to be pitied more than honored. “You honor them regardless of how rich or how poor or what color or creed,” Antolini says. “That, to me, makes sense. She has some valid complaints about how her day was being used.”

Still, not all of Jarvis’ eccentricities can be chalked up to gender biases of the day. Accusing any charity that borrowed Mother’s Day language of lining its own pockets seems ungracious at best and paranoid at worst. Antolini also wonders about the naïveté of Jarvis’ desire to establish a nationally recognized memorial for mothers while at the same time wanting to keep it pure and protected. “What did she honestly think was going to happen?” Antolini says.

Only one of Jarvis’ siblings, Josiah, had children, and his granddaughter died childless in the 1980s. Howard Wolfe knew the granddaughter and received many of Anna Jarvis’ papers; he painstakingly transcribed nearly 300 pages' worth of correspondence on a typewriter. As Wolfe wrote in 1962, “Her interesting life, her 84 years of consecration and devotion to a cause … will endear the Jarvis name for all future generations.”

It didn’t quite happen that way. While Mother’s Day continues to be celebrated around the world on the second Sunday in May, Anna Jarvis, along with her particular vision of what she deemed a “holy day” rather than a holiday, are mostly forgotten.

“For the day to be popular, she no longer has to be connected to it,” Antolini says. “Now that the child has grown up, you no longer have to associate it with its mother.”

There was a reason Jarvis emphasized writing letters home rather than relying on greeting cards, which have a tendency to simplify a relationship dynamic that, for many, is complicated. Let’s say you’d like to tell your mother in a letter that she’s truly the best mother you could possibly imagine, just as Jarvis intended. Today, it would be difficult to do so without sounding like an overly sentimental Hallmark card. In other words, the commercial corruption of Mother’s Day has rendered cliché our ability to talk about how wonderful a mother is. A sentiment that at one time might have sounded heartfelt and sincere now sounds like a platitude, as your local Target and Walgreens and Walmart have aisles full of greeting cards for sale with that same sentiment, and millions of sons and daughters will purchase those cards — myself included. Just this week, standing in a checkout line with a handful of Mother’s Day cards (sorry, Ms. Jarvis), the cashier sighed. “I feel bad,” she said. “I’ve been scanning all these cards and I haven’t even bought one yet. They’re so expensive!”

Those sappy cards seem harmless, even helpful. But the trickle-down effect of their trite sayings and inflated prices is sneakier than one might imagine. Perhaps Jarvis knew this. It was a losing battle, but maybe she could see the future more clearly than her contemporaries. Maybe she could see that the Hallmarkification of Mother’s Day would actually make it harder, not easier, to communicate a true, deep, and loving appreciation of mothers.

The author would like to thank West Virginia Wesleyan College’s Katharine Antolini for her assistance with this piece.