Salvation Mountain is a gateway to another world. Or several.

Rising out of a stretch of blistering desert, the mountain is actually a work of "outsider art" at the entrance to Slab City, California's famous squatter community. It's just down the road from the tiny town of Niland and not far from the haunting ruins of Bombay Beach. The way is marked with hand-painted signs.

I made my way to Salvation Mountain earlier this year, driving past wilting palm farms and the toxic expanse of the Salton Sea. Near a brimming canal, I stopped to talk to two older men, one pushing a bike, the other sipping beer from a can.

"This is the desert, man," the guy with the bike told me when I asked why they had come to Slab City. "You can do what you want out here."

Minutes later I arrived at Salvation Mountain, which felt like crossing into a Dr. Seuss story — if Dr. Seuss stories were set in a searing desert commune and surrounded by fancifully-painted, derelict vehicles.

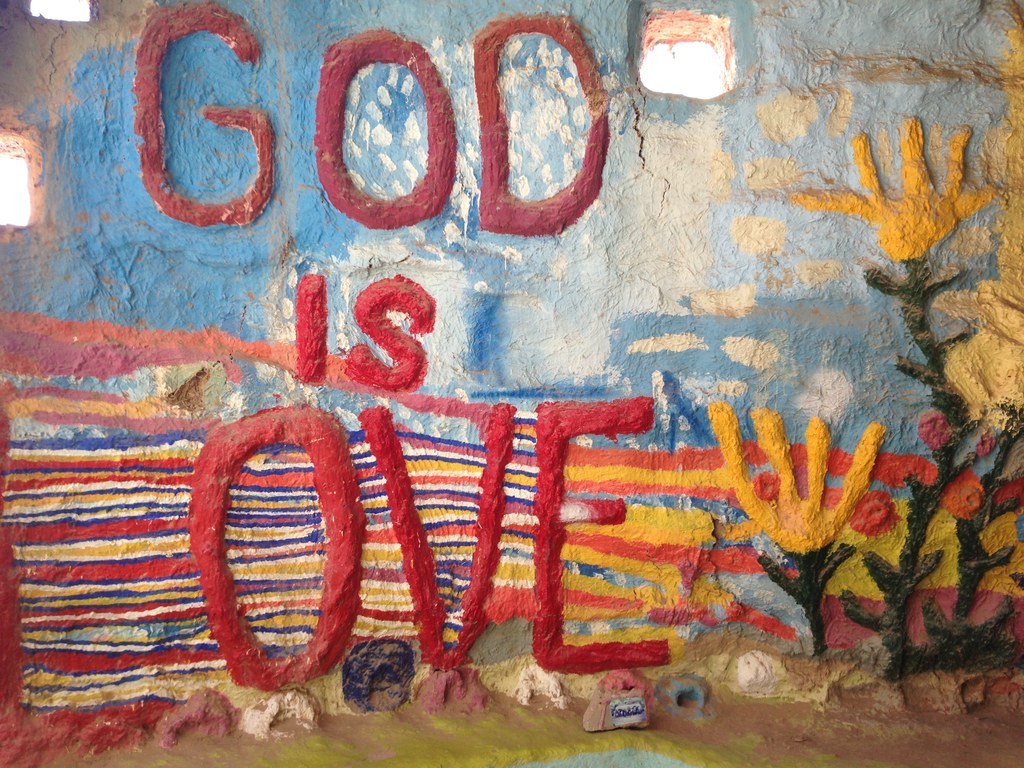

The mountain itself is surprisingly accessible. Aside from a sign asking visitors to stay on the painted "yellow brick road," I was free to walk to the peak, stepping over a painted "waterfall" and through a garden of brightly painted flowers. Messages about God and love towered above me.

Leonard Knight, who built Salvation Mountain, arrived in the area in 1986 while visiting his sister in San Diego. Initially, he wanted to launch a hot air balloon "to send his message of God's love to the world."

The balloon never worked out, but Knight stayed in the area for nearly three decades building the mountain out of hay bales, adobe, and half a million gallons of paint.

The work was still in progress in 2007 when, at the age of 75, Knight was reportedly carrying 40-pound buckets of adobe up a 30-foot ladder. And he was still there in 2010, when an L.A. Times reporter wrote that Knight had no phone, TV, or running water. He reportedly bathed in a natural spring and slept in the bed of an old, broken down fire engine.

"We've just got to start loving God more, and these things like wars wouldn't happen," Knight told the Times reporter. "God's love is the strongest force. It can squash hate."

Knight died in 2014, but members of the Slab City community still maintain the site.

Earlier this year, a woman named Jaime was serving as a host at the site. Jaime leads a nomadic lifestyle — she and her family own an intricately painted bus that they drive around the country in the summer. For the last two winters, they've parked the bus at Slab City, but like the majority of the residents, they leave when the temperatures become practically unbearable.

When I spoke with Jaime, she was sitting with one of her daughters in the shade of her bus, sewing. She said her responsibilities include helping maintain the adobe and paint on Salvation Mountain, as well as answering questions from inquisitive visitors.

Later, I wandered into the "cave." It's a twisting series of chambers filled with messages about God, painted car doors, and branches. Some chambers resemble the side chapels in a cathedral, and have ledges where visitors have left messages. Others feel like part of a forest. It's a world held together with adobe and coated in paint.

Beyond Salvation Mountain, Slab City stretches into the desert. The concrete slabs that remained from an abandoned military base were later used by people who came to live (more or less) off the grid. Today, the area is dotted with mobile homes and trailers.

The community is famous around the world — it appeared in the movie Into the Wild, among other things — and has long been a haven for those who, like the man I met earlier, want to "do what you want out here."