There is a potential legal loophole that Nicola Sturgeon could exploit in order to be able to hold a second independence referendum without Theresa May's permission, legal experts have told BuzzFeed News.

Speaking at an event at Stanford University on Tuesday, the first minister pointed out that the question of whether or not the Scottish parliament must be granted permission from the UK government to hold a referendum has "never been tested in court".

Speaking about the Scotland Act – which sets out what powers are devolved to the Scottish parliament – Sturgeon said: “One of the things it reserved to the UK government is the constitution, which is quite a vague term.

"It’s never been tested in court but in 2014 we accepted that for there to be a referendum in Scotland, for the Scottish parliament to legislate for a referendum, it required the legal consent of the UK government.”

Last week, Sturgeon formally requested to begin negotiations with May over the holding of another referendum, but the UK government has made clear that it has no intention of opening up discussions before the UK has left the EU.

On Wednesday, BuzzFeed News asked constitutional experts what case the Scottish government could bring forward, and they said it boils down to the wording of the Scotland Act and if it explicitly rules out Holyrood holding referendums.

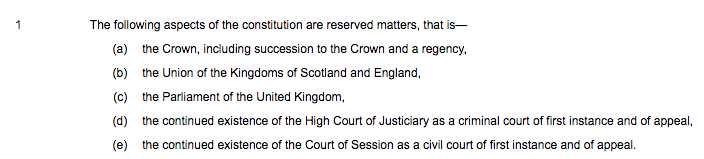

The relevant schedule of the Scotland Act states aspects of the constitution are reserved to Westminster such as the Crown, the parliament of the UK, and, importantly, "the Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England".

However, if the Scottish government takes the case for holding a referendum to court, it's likely to argue that the holding of an advisory referendum – just like the EU referendum of last year – has no direct legal effect on the union as it's not binding in law, and therefore not beyond Holyrood's power.

"The argument essentially is that the power to hold a referendum on independence is not included in the reservation of 'the union' to Westminster," said Aileen McHarg, a professor of public law at Strathclyde University.

"Holyrood can't legislate on anything that 'relates to' a reserved matter – so the question is, does a referendum relate to the union? Literally, yes, but statutes aren't always interpreted literally, and in determining issue, courts have to take account of the purpose and effect of a statute.

"Given any referendum would be advisory only, and, if there's another No vote, would have no effect on the union at all, the argument would be that it does not sufficiently relate to the union to be ultra vires [beyond Holyrood's power]."

Asked if such an argument could succeed, McHarg said: "It's arguable, and I'd say strengthened by the Supreme Court case [brought by Gina Miller], where the judges were all very clear that the effect of an advisory referendum was political not legal."

Professor Nick Barber, an expert in constitutional law from Oxford University, said: "The legal position is not clear, but I would take the view that the Scottish government could hold an advisory referendum on independence.

"Matters related to the Union are reserved, but whilst the Scottish parliament and government lack the power to make decisions within reserved areas it does not follow they lack the power to form opinions on these matters or to negotiate on these issues with Westminster.

"An advisory referendum on a reserved issue would be a way in which the Scottish institutions could demonstrate the strength of feeling in Scotland on the issue, and could play a part in that negotiation process."

However, Barber added of an advisory vote: "Westminster wouldn't be bound to accept the outcome – and the process might be weakened from the start by a declaration from Westminster that it would not recognise the outcome of the vote."

Christine Bell, a professor of constitutional law at the University of Edinburgh, added: "The argument would go something like: It is only an advisory referendum, and if the wording was carefully chosen, it would be made to sound more advisory."

A Scottish government source said this sort of action is not something that is being considered at the moment, and a spokesperson made clear the first minister is still seeking the same legal arrangement that led to the 2014 referendum.

“There is a cast-iron democratic mandate for giving the people of Scotland a choice on their future – and the referendum we are intent on delivering is the same kind as that which took place in 2014," said a spokesperson for the first minister.

“We agree with the prime minister that now is not the time for a vote, but if the UK government’s intention is to try and indefinitely block a referendum, that would be utterly undemocratic and unsustainable.

“People across Scotland already disagree with that stance, and public opinion is only likely to turn even more sharply against the PM the longer she tries to stick to that position.”