As the EU referendum (finally) enters its last week, more and more voters are getting leaflets through their doors from both official and unofficial campaigns.

Unsurprisingly in a debate where both sides have accused the other of making false or misleading claims, lots of voters are unhappy about some of the literature they've been receiving.

For the final week of the referendum campaign, UKIP has launched a controversial poster campaign warning that the EU has driven the UK to "BREAKING POINT" on migration – the poster actually shows refugees being escorted to a camp in Slovenia – while Remain campaigners showcased a rival poster warning that Nigel Farage would be a minister in a post-Brexit government.

Side by side. @Ukip poster on controlling borders. And REMAIN poster saying 'Don't wake up with Nigel' after #EUref

One leaflet from the official Vote Leave campaign has got several people angry, either about it looking like a neutral or official piece of information, or about some of its claims on immigration and the cost of the EU.

"Official information" - Vote Leave leaflet copying the look & feel of a polling card. A tactic that oozes contempt.

I rarely post about this stuff but this official looking leaflet posted by #VoteLeave is deliberately misleading.

Shameful #voteleave leaflet -UK Stats boss has told you not to use £350m. Also states 'official info' as if from gov

An unofficial leaflet promoted by a supporter of Brexit goes even further, suggesting Lebanon, Jordan, and even Syria are "projected" to join the EU "by 2030" – an idea no serious political figure thinks is remotely credible.

@SophieWarnes @MichaelPDeacon I can outdo that. I scanned a leaflet that came through my door with this map in.

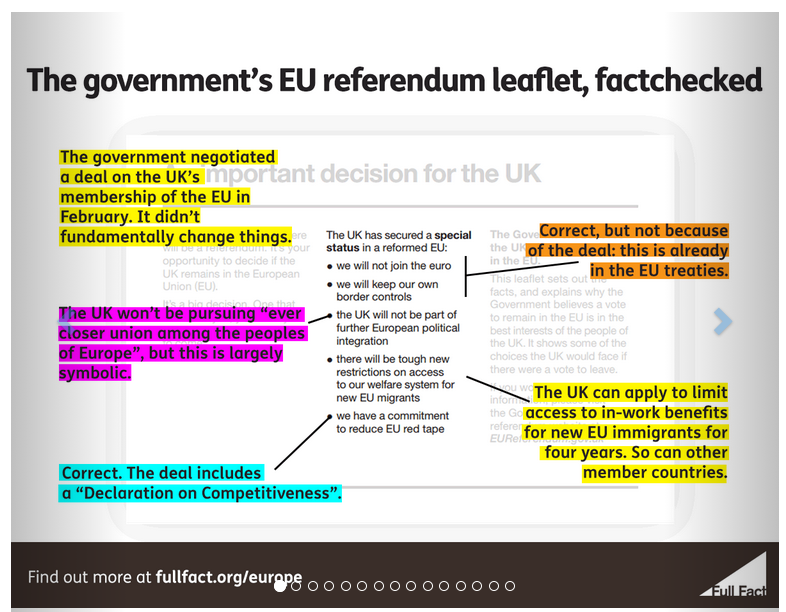

It's not just the Leave side of the campaign that's been accused of making misleading claims, though. FullFact examined the government's official 15-page leaflet promoting Remain, and found "a number of facts and figures that are highly contestable, or where readers are not given information that they would probably want to know".

Most advertising in the UK is heavily regulated – if it's inaccurate, misleading, promotes unhealthy body images, or breaks any number of other guidelines, adverts can be pulled and advertisers face public criticism. So why is political advertising different?

Before 1999, political adverts in the UK were subject to some of the rules governing other adverts: If they were found to be offensive, the advertiser could be criticised and the advert barred from being shown again. However, given regulators often take several months to rule and political campaigns only generally last six weeks or so, such rulings would come far too late.

In 1999, political adverts – any advert trying to influence a vote at election or referendum, whether or not it's from a political party – were dropped from the codes governing other advertising.

There are some rules governing political adverts, but they mainly concern banning paid-for TV adverts and requiring for political leaflets and posters to state who is "promoting" the leaflet.

Any attempt to find somewhere to complain about a leaflet will quickly end in frustration.

Ahead of last year's general election, the Advertising Standards Agency (ASA) offered the following advice:

As the 2015 General Election approaches, we’re reminding everyone why we can’t look into complaints about political ads - they’re not subject to

the Advertising Code. The best course of action for anyone with

concerns about a political ad is to contact the party responsible and

exercise your democratic right to tell them what you think.

The Electoral Commission, which regulates all other aspects of elections – party spending, donations, and other conduct – has a prominent link on its page regarding complaints about political adverts. However, it shows the following:

We frequently receive complaints about political advertising or campaign material and the behaviour of candidates, especially in the period before an election. These are not within the scope of the complaints policy and will be referred to our Public Information Team.

While we have regulatory duties relating to campaign spending, including in relation to political advertising/election material, we have very few powers to deal with the content of material published by candidates and parties, or their general conduct.

Because neither the election watchdog nor the advertising watchdog will look at political adverts, the strange result is that if you tell a lie to sell washing-up liquid, you'll get in trouble. But if you tell a lie to win an election, there are no consequences.

This strange result is one that the authorities have been aware of for more than a decade, and it's been subject to official reviews more than once.

The biggest review was published by the Electoral Commission in 2004, and found, maybe ironically, that one of the biggest barriers to regulating political advertising was the Human Rights Act – the legislation which makes the European Convention on Human Rights part of UK law.

The main reasons the commission gave for not introducing rules on political adverts were:

- A statutory code on political advertising is unsustainable given the right to free speech enshrined under the Human Rights Act;

- To seek to control misleading and untruthful advertising would be inappropriate given the subjective nature of political claims. There is a stronger case in principle for a voluntary code to protect against offensive advertising, which might be in the public interest;

- Any code would require the support of political advertisers. Only the Liberal Democrats and Plaid Cymru have indicated their willingness to support the introduction of a code.

- A system considering complaints is unlikely to deliver sufficiently prompt adjudications to be of any value

The result of that 12-year-old report was the commission urging political parties to gather together and agree on a code of self-regulation to police political adverts. This never happened.

Last year, the Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP) wrote an update on the status of political advertising. It concluded:

CAP continues to urge the political parties to put self-regulation into

practice and write and follow their own Code. In June 2004, the

Electoral Commission reported that, although the Committee on Standards

in Public Life had urged the political parties to adopt a new code of

practice, self-regulation by the political parties was unlikely to be

achieved.

The list of options left is short. The Electoral Commission and ASA suggest if you don't like a political advert, you can complain directly to the advertiser – if you think that will help.

The only remaining option, of course, is the ballot box on election day.