In 2013, Walt Disney Studios made fairly quiet and fairly dismal history. “Frozen” won the Oscar for Best Animated Feature, marking the first time that a female director won the award, although she had to share with her two male co-directors. Jennifer Lee was the first, and so far last, female director that Disney ever hired.

The next female director of a Disney feature film will be Meg LeFauve for “Gigantic,” a retelling of Jack and the Beanstalk due out in 2018. Like Lee, LeFauve will not be working alone and will be directing with Nathan Greno. In between “Frozen” and “Gigantic,” Disney will have released fifteen new movies, all with teams led by men.

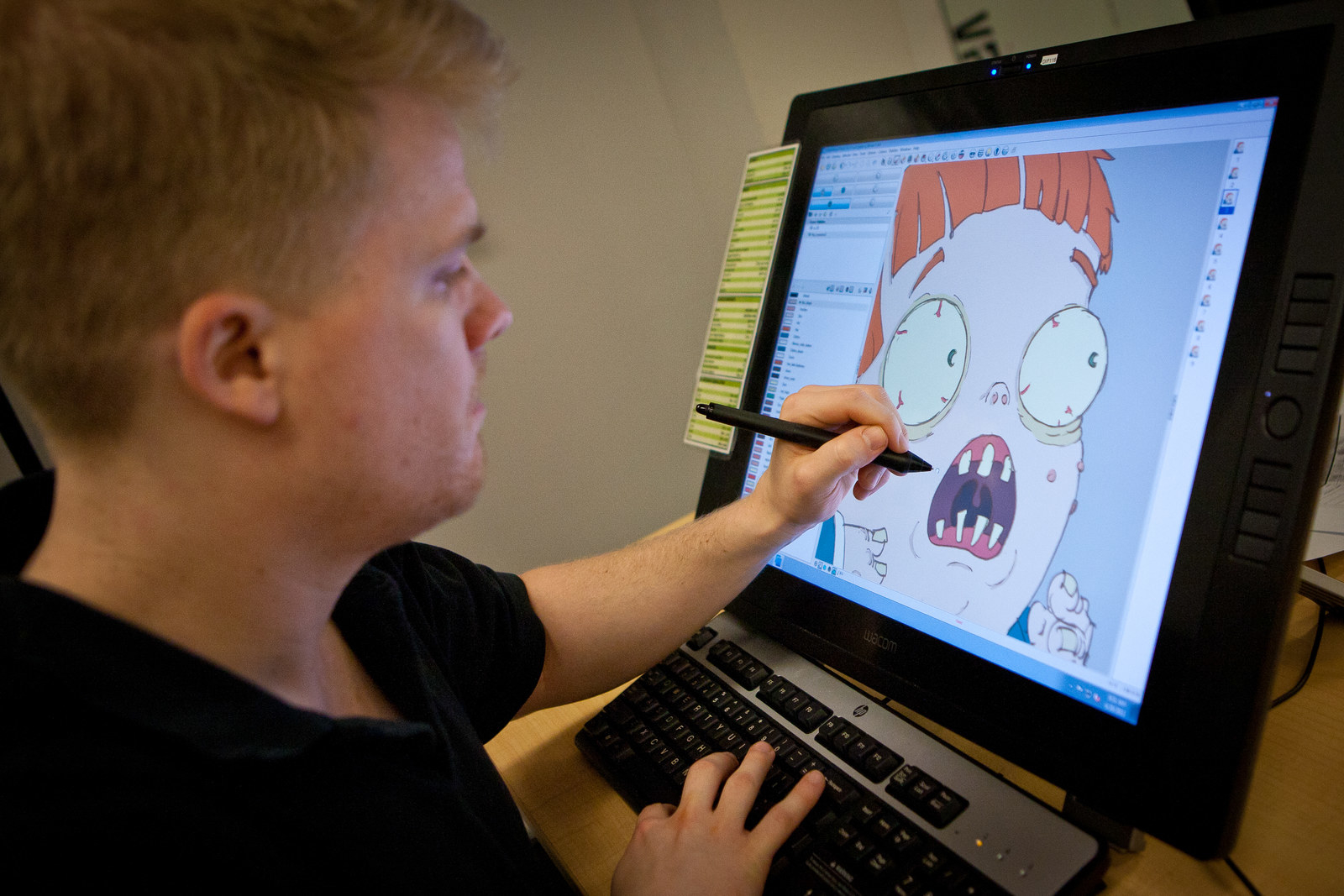

According to data collected by the Animation Guild in 2006 of studios in the Los Angeles area, men make up 84 percent of the animation workforce. After nine years, the Animation Guild collected their data again, from the same area in Los Angeles, this time finding that men now make up 80 percent and women, 20 percent.

According to Rachel Oftedahl, an adjunct professor at Columbia College in Chicago and a freelance animator, Chicago has a similar climate as Los Angeles. The city has a motion graphics group that is over 300 members and Oftedahl says that the majority are men. There is also a women-only motion graphics group, which has 20 total members.

As a freelance animator, Oftedahl finds it harder to be a woman and work with clients. She worked for a television company for three years and found that their clients generally preferred to work with men.

“When a woman pushed back, it was perceived as bitchiness and the client became more resistant to listen to her,” she said. “When the men pushed back, it was seen as them just doing their job.”

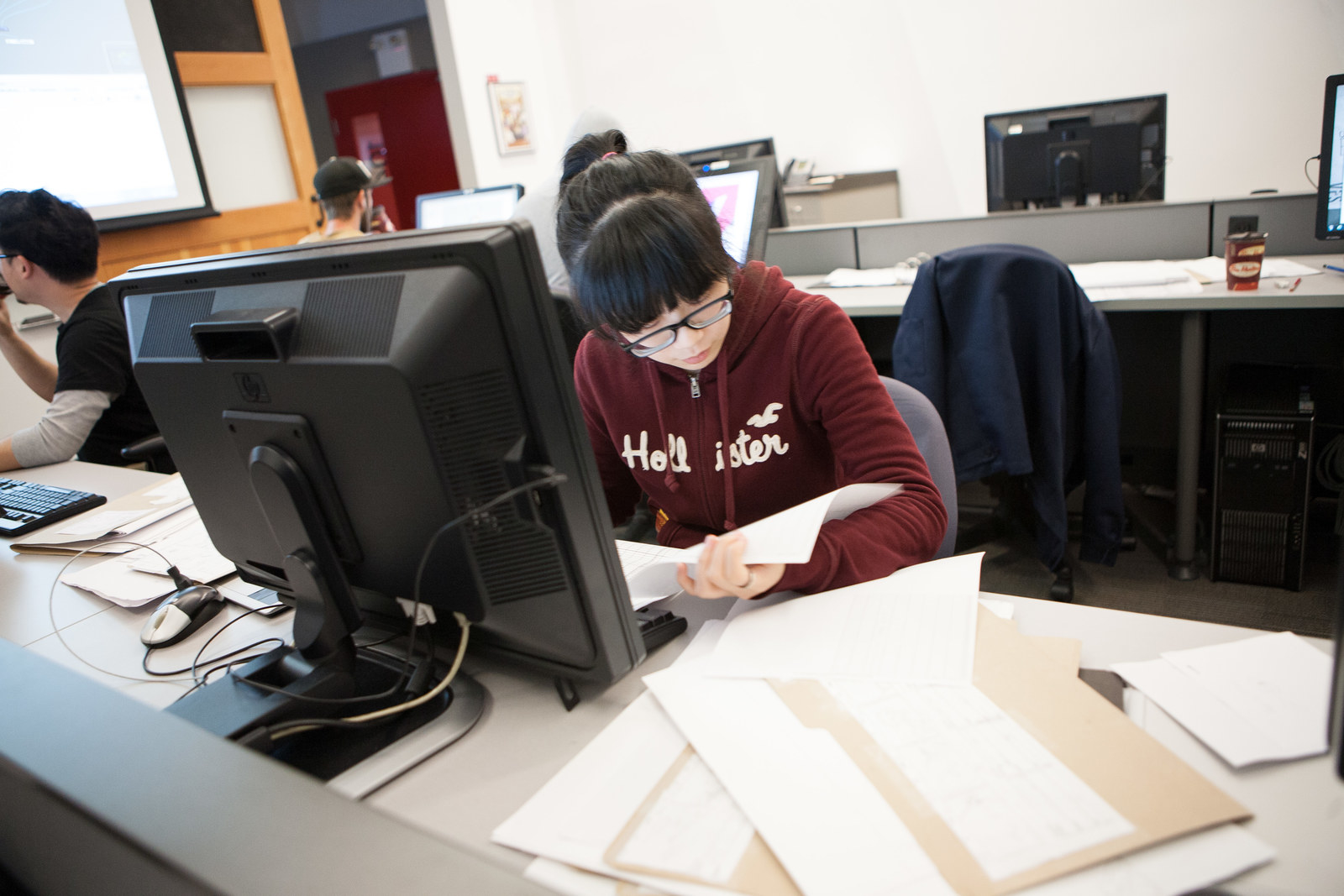

Despite the difficulty that women have in breaking into and being a part of the animation industry, Oftedahl has seen a great increase in interest in animation from women. As a professor of animation and motion graphics, the majority of her classes had been dominated by male students, until last semester, when she taught a 3-D motion graphics class. The department head informed her that it was the first animation class that the college ever had where all the students were women.

The increase in interest in the field by women unfortunately does not reflect an increase in job opportunities. A survey of LA based colleges, taken in 2015 by the Animation Guild, showed that 60 percent of animation students were female, a vast difference between the 20 percent of women holding jobs in animation. Women in Animation released these statistics and they also collected data to find how many solo female directors of animated features were hired in the past 15 years in the US. There were only two: Jennifer Yuh Nelson for “Kung Fu Panda 2” and Jun Falkenstein for “The Tigger Movie.”

Those are the kinds of statistics that worry Brianna Hayes, an education and fine arts student at the Moore College of Art and Design in Philadelphia. Her animated short film “Ontology” was shown at her school’s Women in Animation Film Festival in March. Although her work is being shown now, she worries about whether or not there will be a place for it after she graduates.

“I’m not worried about getting a teaching job because teachers are primarily female,” she said. “But I am nervous about getting my work exhibited.”

Margaret Polzine identifies as nonbinary, but they say that they often present more as female. They now work in Minnesota, doing experimental animation. Like Hayes, Polzine worries about getting her work exhibited, but for a different reason.

Polzine says that they’re unsure where their place is. Although they typically show their work at women’s film festivals, they say that they feel like they are “tricking people” just because they can pass fairly easily as female. The festivals that aren’t just for women, however, feel “stuck in the cisgender male narrative,” Polzine said, which leads to them being uncomfortable showing their often feminist work.

“The climate in the twin cities has always been a boy’s club. I never wanted to work in a studio,” Polzine said, “but years ago I met a studio representative. He referred to all the employees in the studio as bros and called the studio itself ‘the man cave.’ It made me feel gross. I never felt comfortable being a part of that. ”

Polzine makes it their responsibility to include feminist and LGBTQ stories and values in their work and believes that going away from how we know animation today can pave the way for inclusivity inside our movies and inside our studios. When we stop thinking of big studios as the only way to animate, we can make animation less money orientated and more focused on content instead.

“A lot of people know the big names like Dreamworks and Disney,” they said. “They know princesses and nothing else.”

Polzine does, however, remain cynical that companies are going to change. They saw from studio representatives that companies want to hire someone who “meshes” with what they already have and what they are already doing. Studios are inherently money oriented. There is little incentive for a studio to change a formula that already works. A lot of animation jobs come from advertising companies and production companies, both of which have a long history of being predominantly male. It’s this idea of needing someone to mesh that prevents studios from being able to break away from the boy’s club. If the company is already male, then the people who are going to mesh best would be men too. Like Polzine saw with the studio representative, some hiring managers don’t want to hire someone that they can’t see as their “bro.”

Although companies have been responding to activism to change characters on screen, like Disney’s inclusion of princesses with more diverse backgrounds, like we saw with their newest princess Moana, the issue remains that there has not been much change in the studios itself. As long as studios are considered “man caves” or “boys’ clubs,” women will remain on the outside looking in.

“It’s important for companies to go off the beaten path, both with who they hire and what they create,” said Polzine. “If they do that, they can go to such great heights.”