During Beyoncé’s recent Grammys performance, she may or may not have been evoking a centuries old Pan-African water deity, Mami Wata. Unabashedly showing her pregnant belly, she danced with a flowing yellow cloth reminiscent of her jaw dropping “Hold Up” dress. The only words were the poetry of Warsan Shire: “Do you remember being born? Are you thankful for the hips that cracked, the deep velvet of your mother and her mother and her mother?”

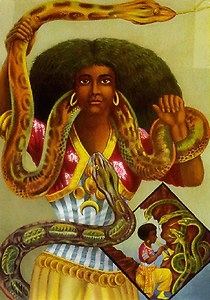

This wasn’t the first time Bey has been compared to Mami Wata, a half-human, half-mermaid-esque creature worshiped in many parts of Africa as well as diaspora communities around the world. While she has many interpretations, at her core, Mami Wata is an embodiment of water, both as a destructive force and a source of life. In some stories, she’s a sexual figure, luring men to their watery graves. In others, she’s a mother associated with the power of fertility. Along the West African coast, she is known as various versions of the name “Mami Wata.” In Brazil, she is Yemonjá and in Cuba, Yemanya. In the Caribbean, she is la Sirène or la Baleine (Haiti), River Mama/Mumma (Jamaica) and Maman de l’Eau (Guadeloupe).

Although many traditional African religions were suppressed by Christianity during the colonial era, Mami Wata never stopped being revered. Conversely, while she is worshipped globally, Mami Wata is most commonly recognized from a 19th century advertisement for a traveling "exotic people and animal" show.

Consequently, in recent years, many artists of African descent have worked to reclaim Mami Wata, including through a multimedia group show in New York this past summer aptly named MAMI. One reason artists have turned to Mami Wata is the trauma many people of African descent associate with water. It’s difficult to determine, but of the at least 12 million slaves taken out of Africa during the 19th century, an estimated 15 percent died while crossing the Atlantic Ocean. Once in the Americas, life expectancy on many plantations was only seven to nine years.

While artists have used many symbols to represent this horrific history, Mami Wata is only beginning to enter mainstream pop culture, particularly through the work of Beyoncé and other black female artists.

Most notably is Bey’s standout “Lemonaide” track “Formation.” The backbone of the music video finds Beyoncé in a post-Katrina New Orleans. The video is full of gifable moments, but the most halting might be the opening and closing shot of the singer in a simple, retro dress on top of a police car slowly sinking in the water. The power of water for both creation and annihilation is clear as Beyoncé escapes the water as the song transitions. Bursting through the doors of a mansion, she escapes her watery fortress and turns her anger into action during the bitter “Hold Up.”

And it’s not just Beyoncé, a worshiped deity herself, who has evoked Mami Wata. In the video for FKA twigs’s 2014 song “Two Weeks,” the camera slowly pulls back, revealing the British singer to be sitting on a throne with a group of female attendants, dressed and covered in glistening gold.

While it is clear that her magic is connected to water, as drops flow from her fingers into the mouths of one of her dancers, it isn’t until the end of the song that twig’s full power is displayed. While it seemed the camera was only inches away from the artist, it is revealed a pool of misty water separates the two, giving her a sense of distance from the viewer. It’s obvious that twigs is untouchable. The camera then goes underwater, revealing a second twigs floating in a red dress. The video ends with her looking into the camera, leaving it unclear whether her watery depths are her cage or her kingdom.

This isn’t the only time that twigs has represented a Mami Wata-esque figure. In the video for “Pendulum, “ the camera once again plays with close ups, as it starts with a shot of just her lush pink lips.

As the camera zooms out, her full body tied in bondage is shown. The singer, who has a background in dance, is suspended on a pendulum, almost like a ballerina. Throughout the surreal clip, she finds both comfort and constraint in her bounds, before she is eventually enveloped in a pool of silver mercury. The special effects are creepy, as twigs’ face morphs into the water, as if they have become one. Then, like Mami Wata, she sucks the viewer in with her.

On the other side, twigs is free. Her hair, which had previously formed braids used to control and constrict her, is now let loose. No longer in bounds, she moves on an artificial sea of water made up of thousands of screens. Unlike in “Two Weeks,” it’s evident that here, twigs’s power is connected to water. This is a theme in her lyrics as well, such as the single “Water Me,” in which she connects water to sexual thirst.

“He told me I was so small

I told him ‘Water me

I promise I can grow tall

When making love is free’”

Of course, it is not only modern artists whose work conjures an image of Mami Wata. In girl group TLC’s cautionary “Waterfalls,” the trio warns an anonymous man, a brother or lover, to not become involved with gang violence and having unsafe sex.

The song came out in 1994, the year “AIDS became the leading cause of death for all Americans ages 25 to 44.” Even though the track never directly mentions the epidemic, the main character’s story ends with “Three letters took him to his final resting place.”

Here, water, and waterfalls in particular, embody a societal moment in which a mysterious and deadly disease was causing an international crisis. TLC (aka Tionne “T-Boz” Watkins, Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes” and Rozonda “Chilli” Thomas) can only plead to the song’s subject, and arguably their wider audience, to “Don't go chasing waterfalls. Please stick to the rivers and the lakes that you're used to.”

In the video, Watkins, Lopes and Thomas emerge from the water as Mami-like figures. More than 20 years later, the special effects are pretty cheesy (though it was clearly a precursor to twigs’s videos). But it is obvious that the rappers aren't characters in the song. Instead, they are all-knowing narrators, dancing under waterfalls and literally becoming figures made of water. These shots, which add to the video’s mythical element, are a contrast to the scenes depicting the very real effects of gun violence and HIV/AIDs. Even if in this instance, water and Mami Wata have negative connotations, TLC as her disciples are trying to send a warning. As the video ends with ghosts and empty picture frames haunting those who survived, the bodies of TLC once again turn back into liquid, sinking back into the water.

While these songs use Mami Wata to comment on current issues, they are following a long tradition. For centuries, Mami Wata has been a reflection of the sociopolitical realities of her followers, given water’s connections to agriculture and trade as well as natural disasters. Now in 2017, water has new political connections given the ongoing water crisis in Flint, Michigan, a majority Black city where budget saving measures led to thousands of children being exposed to lead poisoning in the water. Despite the clear evidence, local officials have been slow in providing long-term solutions for clean water. And it’s not just in Flint. Bad water quality levels in cities around the country, often those with large African American populations, have raised the question of whether this is a form of environmental racism.

While Beyoncé is making a statement, it’s hard to connect a national water crisis with a highly stylized awards show performance and music video (though she did donate $82,000 last year to help the situation in Flint). Conversely, if Mama Wata can be a conduit for social change in the 21st century as humans continue to wreck havoc on the environment, it might be as a force for connecting the global African diaspora. While she’s a mythical figure, her complicated legacy of being both good and evil is, at its core, a human experience. It might just be that she has so many identities, sometimes a trickster vixen, sometimes a knowing mother, that so many people can see themselves in Mami.