"What happens next will be life or death for me," says Sarah Long. "Without treatment I will slip back into a very dark place."

Long has a rare growth-limiting disease called Morquio syndrome, which leads to short stature, joint abnormalities, limited mobility, and problems with organs such as the heart and lungs. Most people with the condition are dead by 25, so, at 44, Long is unusual.

For the last three years, things have been looking up. In 2012, Long joined the trial of a new drug, Vimizim, the first treatment for Morquio. Along with 34 others, most of them children, Long began weekly trips to the hospital to be infused with the drug intravenously. It worked.

After beginning the trial, Long's life was transformed. Her thoughts are clearer and she's embarked on a PhD. She's no longer in excruciating pain and is able to sleep through the night without oxygen tanks. Long tells me matter-of-factly that she would be dead without the drug.

As of last Wednesday, however, thanks to delays in the NHS appraisal process for funding rare-disease treatments, Long's medication has been halted. There is no guarantee it will be reinstated.

"It feels like a death sentence," Long wrote in an open letter to David Cameron. "Can you imagine what it is like being locked inside a body, a fog distancing myself from others? Every day, struggling to breathe, choking on thick mucus, ever amazed at the volume I used to cough up. Wondering if my arms, hands or other limbs will be working each day."

The catalogue of the procrastination and paper-pushing that has led to this situation is substantial.

The Vimizim trial in the UK came to an end in 2014 as the drug was approved and licensed by the European Medicines Agency (EMA). Vimizim is now available in more than 30 countries, including France, Germany, Greece, Spain, and the Czech Republic. But not in the UK. Here, the decision-making process drags on.

In 2013, the government ditched its old method of evaluating the funding of rare disease medication. However, last December, the new process – a "scorecard" of benefits and costs relating to new drugs – was scrapped after a judicial review by a Morquio patient revealed it to be flawed and unfair.

Until recently, BioMarin, the California-based pharmaceutical company that makes the drug, continued to provide Vimizim to the UK cohort. However the free supplies stopped last week, and, with the drug's price-tag north of £300,000 a year, it's out of reach for most people to self-fund.

"Taking part in the trial was a massive undertaking," says Donna Halleron, whose 11-year-old daughter, Enola, was one of the Vimizim group. "A day a week in hospital for what we thought was rest of our lives. It was also a risk but it was one we thought was worth taking because of how the disease progresses."

Halleron is furious. She says her daughter has been used to demonstrate the drug's effectiveness for the rest of the world without being looked after in return. She and Enola feel abandoned.

"I hope the people who are making these decisions can sleep at night, because they've got people's lives in their hands," Halleron says.

This January, the NHS launched a three-month public consultation into its investment decisions around treatments and drug funding. In terms of Vimizim specifically, an interim review by NICE questioned the drug's effectiveness, suggesting it does not prolong life.

"The independent medicines assessors NICE have raised real doubts about Vimizim," an NHS spokesperson tells BuzzFeed News, "however there is an annual process where the NHS carefully identifies the best new treatments and that's now happening."

NICE says its final guidance will be ready in October. A spokesperson tells BuzzFeed News: "We consider, via an evaluation report commissioned from an independent academic centre, all the published evidence about a drug's efficacy and value for money."

The Society for Mucopolysaccharide Diseases (the MPS Society) and others in the Vimizim trial group are questioning NICE's findings. Long is certain that Vimizim has lengthened her life. Without it, she says, "I can't see much future for myself." It's unlikely her PhD will be finished. Soon she'll be unable to breathe unaided. Eventually, her body will simply shut down around her.

BioMarin, a hugely successful profit-generator, is keen to posit its prolonged handouts of Vimizim as compassionate. The firm says it is "committed to finding a long-term funding solution" and claims that the £395,000 figure quoted by NICE is not an accurate reflection of its latest offer to the NHS.

A company spokesperson tells BuzzFeed News: "BioMarin has submitted a patient access scheme proposal to NICE, which would be at a discount to the NHS list price. The details of such schemes are always confidential."

Long knows that people will weigh up the costs of her medication against, say, paying a nurse's wages. But she points out that with a condition like hers, serious infections and problems with the respiratory system mean frequent and lengthy trips to the hospital. On Vimizim, she says, this has all but stopped.

"I only wish I lived in a society that thought my future was an investment," she says. "Now I find myself dehumanised by the processes in place, a non-person."

Halleron, talking on the phone, says her daughter is stoical in the face of possible physical deterioration. She sounds tearful: "Apparently Enola told a teacher at school, 'I might not be able to do much soon because I won't have my medicine.'"

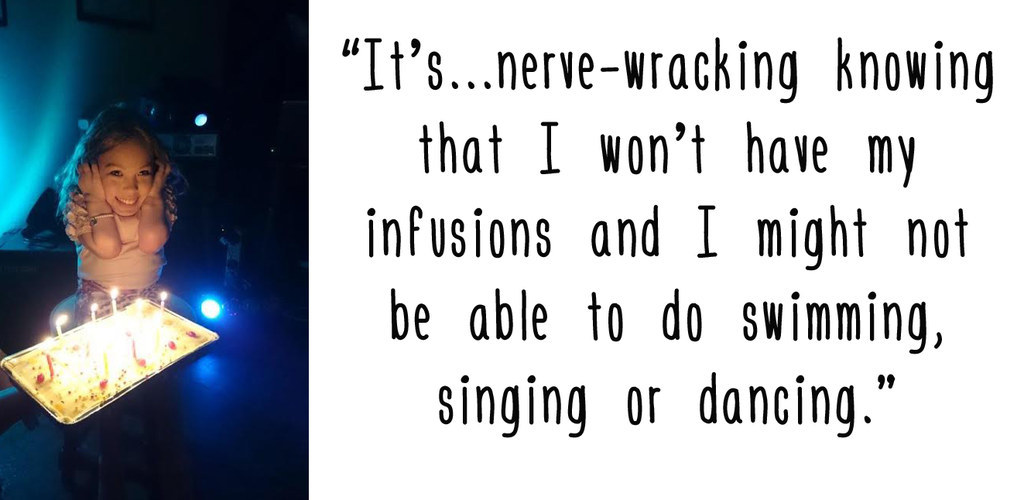

She puts her daughter on the line. "I'm OK," Enola says. "But it's a bit nerve-wracking knowing that I won't have my infusions, and I might not be able to do swimming, singing, or dancing. With my mum here I feel a bit better though."

NHS England will soon announce whether it will fund the treatment on an interim basis until NICE makes its final decision in October. For those who say their lives depend on it, the backtracking and indecision have been brutal.

"These 34 young people must not be made to pay for the mistakes of NHS England," says Charlotte Roberts of the MPS Society. "Time is seriously running out."