For Alisha Mayers, a volunteer at the Mangrove Mas band camp in Ladbroke Grove, west London, Notting Hill Carnival means more than one or two days of partying in the city's streets – it's a rich Caribbean tradition she was born into and grew up around.

"It's special to me because it's one of the only events I can go to and literally feel free," she said. "No one is judging me, no one is watching me. I can literally put on my costume and feel like a million dollars."

Preparation for carnival, Mayers said, takes a whole year. "It's very demanding, especially this time of year. I have to balance work, childcare, I play the steel pan as well. But it's not just me, everybody does."

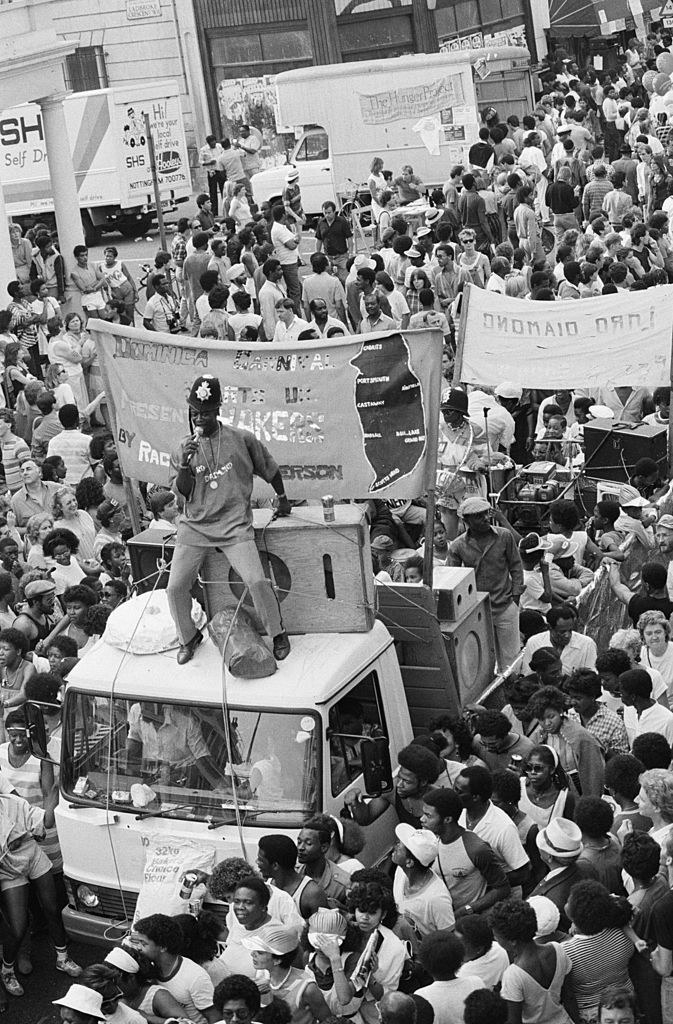

Notting Hill Carnival attracts more than a million people each year. It's the largest street parade in Europe, spanning more than 20 miles across west London – once the beating heart of Britain’s West Indian community, but these days less and less.

This year tentatively marks carnival's 50th anniversary – there's no exact answer to when it started – and is indeed a cause for celebration.

Many are surprised the event has survived this long: Not only does Notting Hill Carnival get no funding worth mentioning, it also relies on volunteers like Mayers to help bring it to life, with older people passing on the skills such as costume design and wire-bending (essential for construction of the giant carnival masks) to the younger generation.

Pressure on local authorities, the Metropolitan police, and even the residents who consider the two-day event an inconvenience have long threatened carnival's future. In July, Conservative MP Victoria Borwick called for a change to the way carnival is run and a move to Hyde Park has been mooted, but for now at least the show will go on.

Carnival kicks off on Saturday night, ahead of the two days of parades, when steel bands from across the country go head to head in a competition called Panorama.

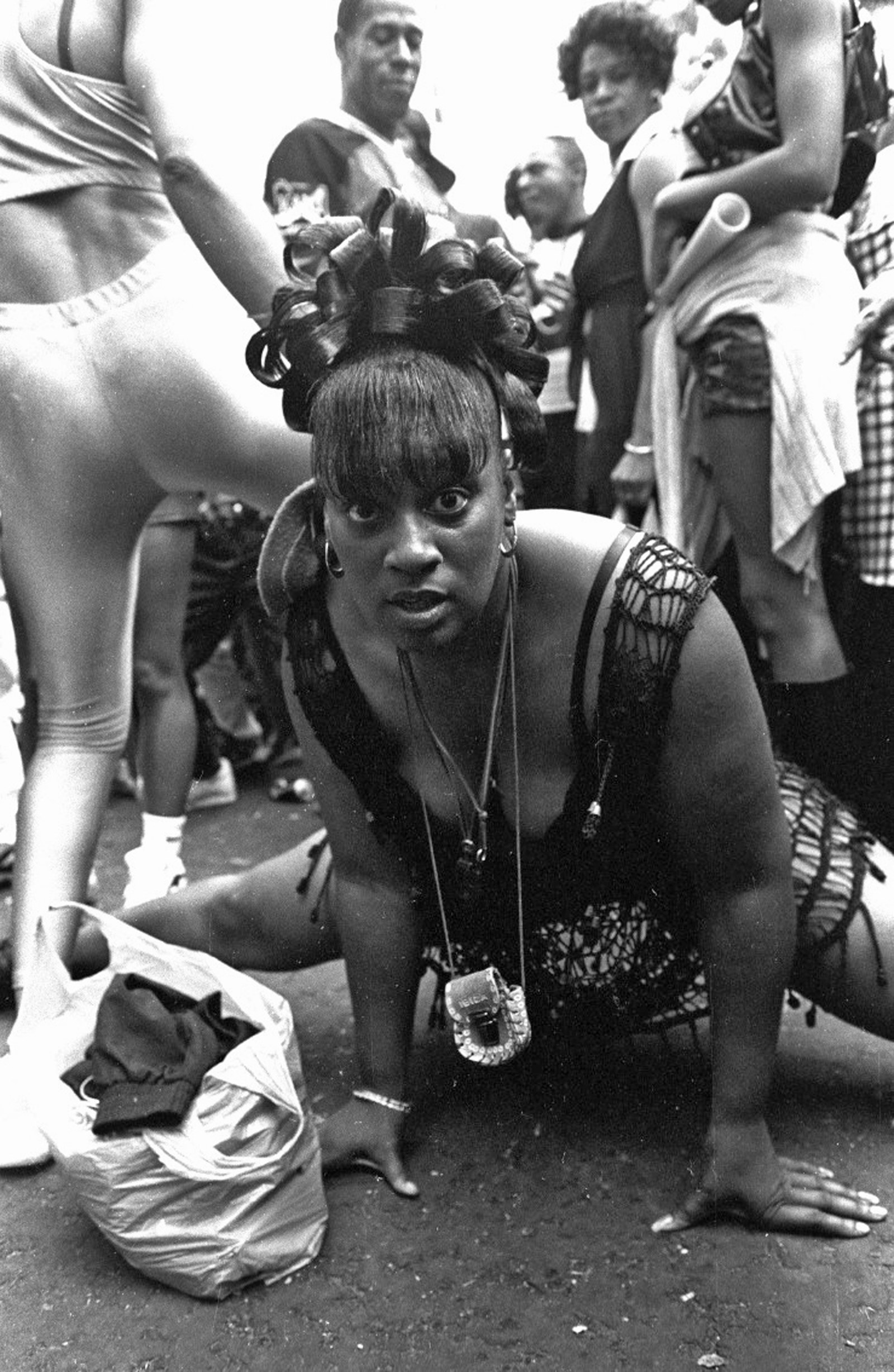

Early on Sunday, there's J'ouvert – a traditional Caribbean carnival procession that takes place before sunrise and involves people covering themselves in mud, though nowadays people use chocolate, paint, and sometimes powder.

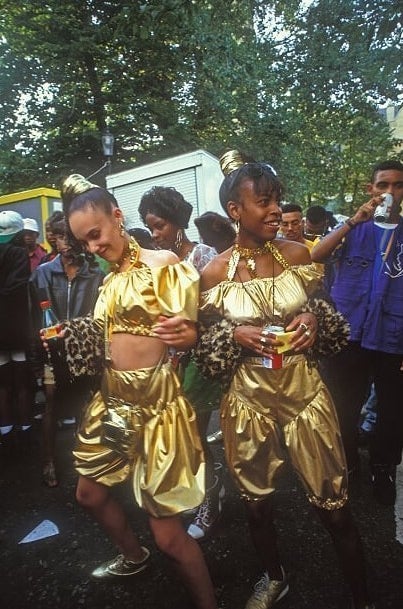

Then comes the two-day parade, involving mas bands (short for masquerade) of between 80 to 300 performers dancing along the carnival route in elaborate costumes to the sound of soca and calypso, styles of music that originate from Trinidad and Tobago.

It was developed by the enslaved West Africans shipped to the Caribbean as free labour, who used it to mock their slave masters.

Nestled in side streets are the booming sound systems, including Channel One and Norman Jay's Good Times, that cater to different musical tastes including drum and bass, hip hop, and samba.

The sound system – which hails from Jamaica – is not part of the traditional Caribbean carnival, photographer Neil Kenlock told BuzzFeed News, and so was met with resistance in carnival's early days.

"Jamaica was the only [Caribbean] island that didn't really do carnival, but they have sound systems and they were stationary," said Kenlock, the co-founder of the now defunct Choice FM – the UK's first radio station for black music. "People with the bands and the floats believed that people should be moving around, whereas people from Jamaica believed that they should be stationary listening to the music.

"As time went on people believed that there can be both."

Nevertheless the mas bands remain one of carnival's most iconic elements. They're scored every year as they pass through a designated judging area, and competition is fierce.

The preparation takes place year-round at different mas camps across London and further afield – and it is estimated more than 1 million hours go into creating the costumes.

The band gives seed money, which is enough to provide the materials for the prototypes to be made. After that, once people pay their registration fees and deposits for their costumes, that money goes towards expensive feathers and stones. These luxurious decorations are expensive. They're shipped in from China and can sometimes take up to 10 weeks to arrive in the UK once ordered online. A lot of the stones are custom-made.

"The more stones you put on the costume, the more expensive the costume has to be," Mayers said. She showed us one costume in the making, carefully decorated with stones worth £4 each.

"Each stone has to be counted; we have to make sure we order the right amount of stones for each costume. Obviously at £4 each, we can't [afford to] overbuy," she added.

"Growing up as an English-born Caribbean," Mayers said, "carnival is a time of year where you remember when you couldn't be as free. My gran used to say to me back in St Vincent that they would celebrate with other [Caribbean] islands that were free from slavery, so, for example, with my cousins in America, in Aruba, or in Jamaica and different places."

She added: "Every family and community has a different idea of where carnival sprung from. But in Notting Hill it came out of a lot of adversity."

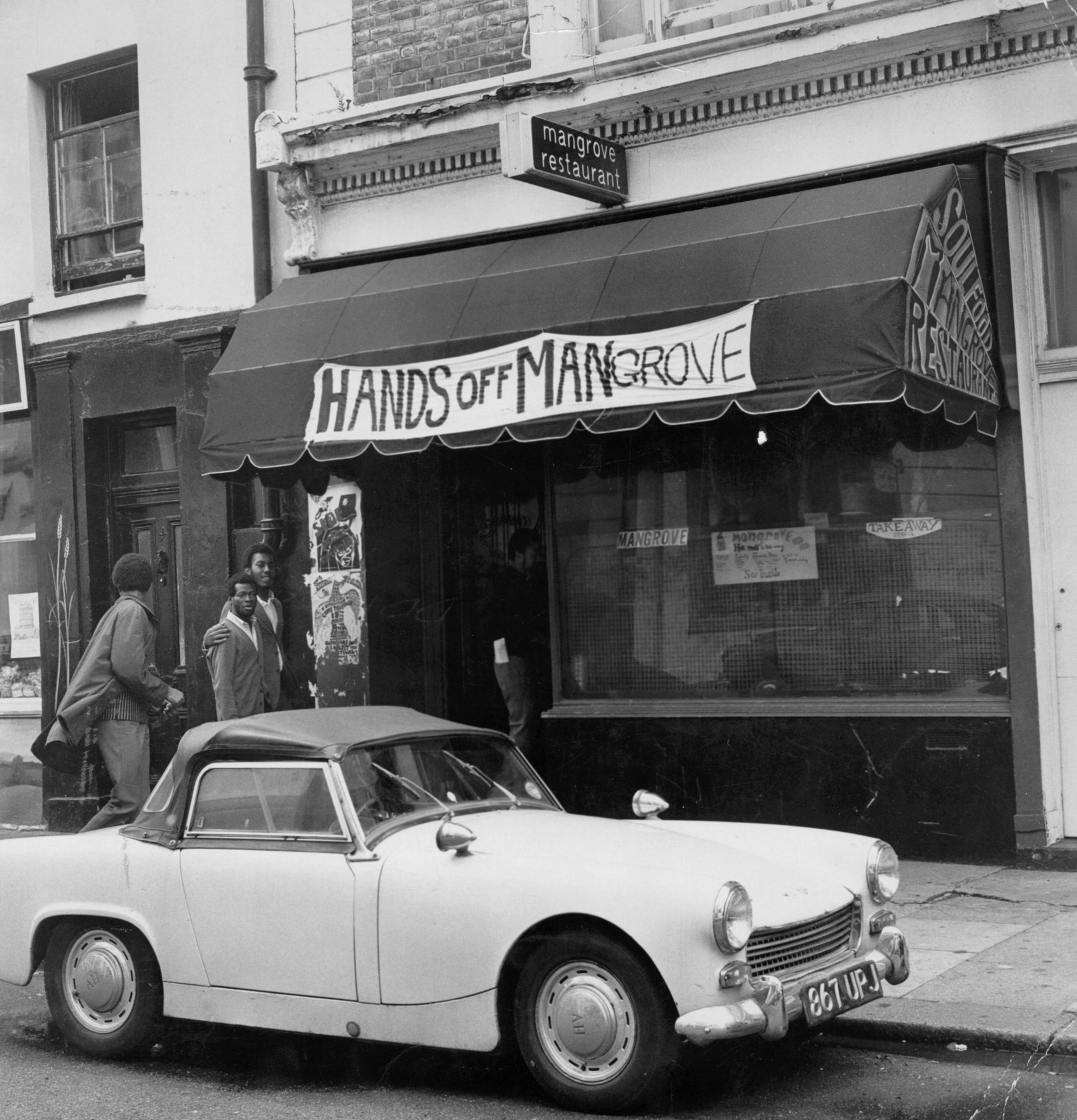

The story of Mangrove, the mas band Mayers belongs to, starts in 1968 with a restaurant of the same name. Situated on All Saints Road, it was one of the first black-owned restaurants in Ladbroke Grove, run by Trinidadian Frank Crichlow, who played an important role in carnival's early days.

The restaurant eventually became the "parent body" for Mangrove's steel and mas band and all the social activities that took place through the Mangrove community association, which ran social support programmes.

For the Caribbean community in the Notting Hill area it was a welcoming gathering place where they could receive support and advice, but the police viewed it as a hotbed of black radicalism and criminality.

The Mangrove was known as a "black power hub and became a major international magnet for celebrities", said Lee Jasper, who in the 1980s became a director of development for a newly developed Mangrove Trust. "It became the number one place to go. Everybody from Marvin Gaye, Muhammad Ali [to] Bob Marley, every major star would come to All Saints Road and they all wanted to meet Frank."

But both Crichlow and the Mangrove Community Association regularly faced police brutality and corruption. Crichlow was regularly accused by police of drug-dealing and petty licensing charges such as allowing his friends to dance and eat sweetcorn after 11pm, The Independent reported. The Mangrove was raided 12 times between between January 1969 and July 1970, but each time police found no evidence to convict the owners.

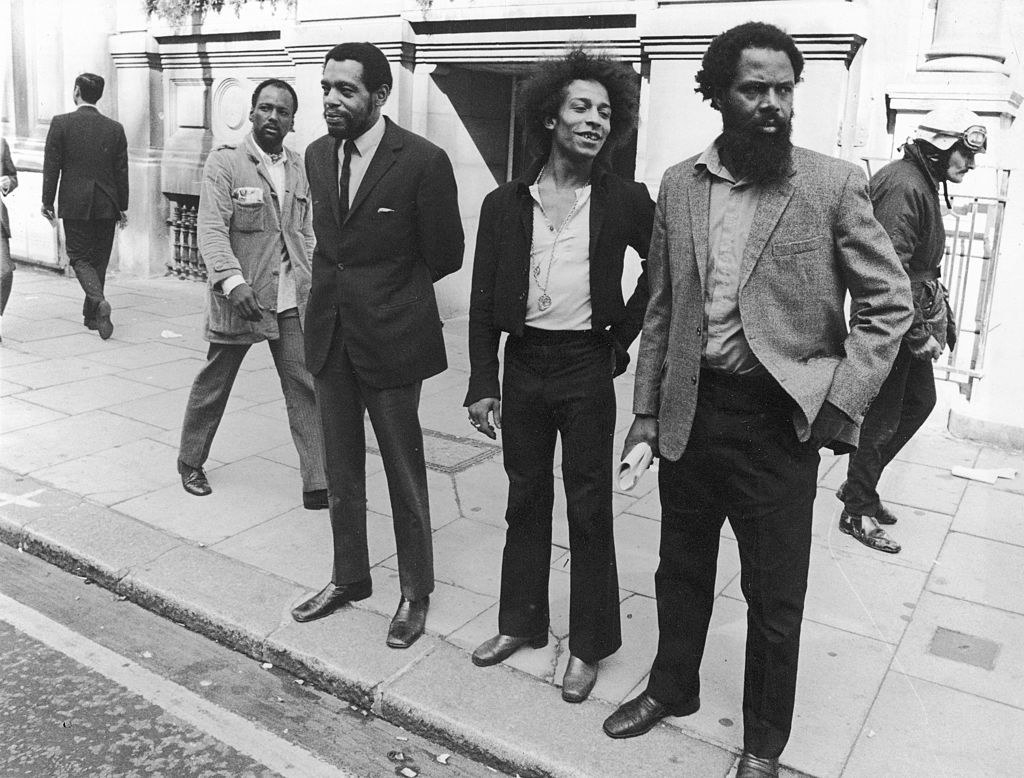

Eventually the police arrested Crichlow with eight others – known as the Mangrove Nine – for "riot and affray". Their trial at the Old Bailey lasted for 55 days and they were acquitted of all charges. Crichlow hailed the verdict as a turning point for black people, The Guardian reported. "It put on trial the attitudes of the police, the Home Office, of everyone towards the black community," he said.

The disruption, however, meant that the Mangrove band had no other option than to practise in All Saints Road in the run-up to carnival, drawing in crowds and helping cement its status as "the people's band". While other steel bands got corporate sponsorship, or local business sponsorship, Mangrove was generally "raggedy", Jasper said. "I remember one time on our way to take part in Panorama we had to carry the float because one of the wheels fell off."

Steel pan practice on the streets continued until Jasper convinced the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea to provide a permanent premises for Mangrove at the Tabernacle, in Powis Square, Notting Hill, where it remains today.

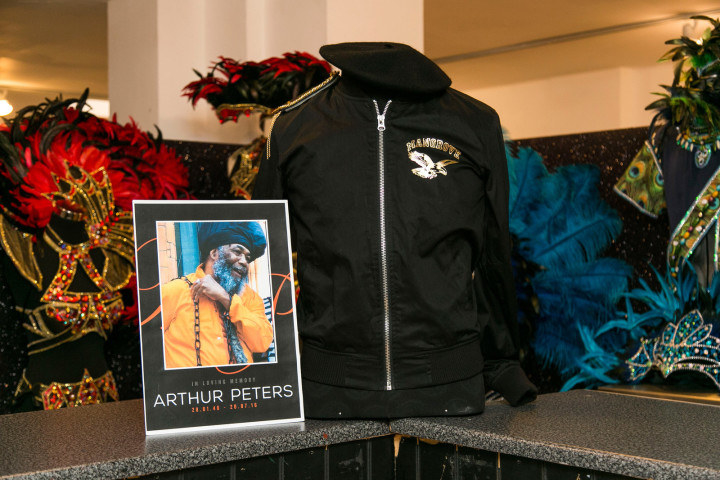

This year, Mangrove will pay tribute to one of its senior members, Arthur Peters, who recently died. Mayers told BuzzFeed News he was such a big part of carnival that they couldn't let the 50th anniversary pass without doing something.

"Arthur Peters was an absolutely fantastic carnivalist," Jasper said. "He was a giant amongst carnivalists, his creative genius, his commitment to steel pan, and just a joy of life. Wherever he went or whenever he spoke people started to smile at him simultaneously."

In terms of its origins, Claudia Jones is often credited as "the mother" of Notting Hill Carnival. The activist and founder of Britain’s first black newspaper, the West Indian Gazette, staged an indoor carnival in King's Cross St Pancras Hall in 1959, filmed by the BBC, and invited the Russell Henderson steel band to perform.

It is thought that in either 1964 or 1965, the same band led by Henderson started an "impromptu jump-up" through the streets of Notting Hill, a traditional Trinidadian procession marking the beginning of carnival. They marched around Portobello Road, and of course attracted a growing crowd.

In 1966, a British woman called Rhaune Laslett invited the steel band to perform at what was then called the London Fayre, and Notting Hill Carnival evolved from there thanks to key players such as Trinidadian Selwyn Baptiste, who became the chairman of the first carnival development committee.

Debora Alleyne-De Gazon, the creative director of the London Notting Hill Carnival Enterprise Trust, told BuzzFeed News the date of the first event is not something that everyone agrees on, which is why they say carnival started in 1964–66.

"In 1965 nothing really happened, [but] we recognise it as the emergence of the [carnival art form]. But 1966 was when Rhaune Laslett decided to use it to reintroduce the London Fayre," said Alleyne-De Gazon. “It was a success, because it did what it intended to do – bring people together and create community cohesion, and it continues to do that today."

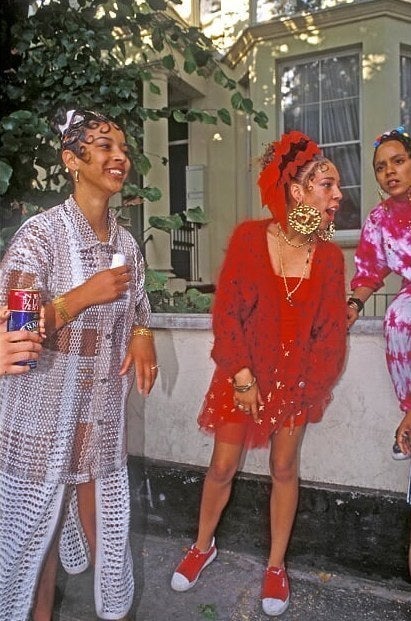

Alleyne-De Gazon said those early carnival musicians "created a nostalgic moment for Notting Hill residents", many of whom were experiencing "trying times" with housing and unemployment, for example. "It was bringing a part of their Caribbean culture to the UK, and people loved it," she added.

Kenlock, who moved to London at the age of 13 from Port Antonio, Jamaica, in 1963, first attended carnival in the late '60s. "It was quite simple, there might have only been about five or ten thousand people there, so it was quite small and peaceful," he told BuzzFeed News.

But during the mid-'70s the carnival began to change, as tensions between the black communities and the police caused unrest and violence. Kenlock believes this mostly stemmed from a lack of understanding of Caribbean culture in the UK.

"The culture of Caribbean people is very different from the culture of British people… and I think [British people] found that very different and sometimes quite threatening. And of course the police didn't understand that these people were basically trying to reconnect with their culture from the Caribbean," he said.

"They would go and arrest people and some people would respond by throwing bottles and stones at them, and it became out of control."

But it wasn't only a disconnect between cultures that caused tension and unrest, he said – black people in Britain were feeling "disconnected with British society in general". "Black people were getting restless... They felt as though they weren't being cared for, and that they were not part of Britain.

"This [carnival] was their culture and their enjoyment, and society didn't seem to care about their culture so they had to resist and fight for change, and that's what caused some of the violence in the early days."

A statement on Wednesday from the Met suggests these attitudes have changed. "Well over 1 million people attend the Notting Hill Carnival every year; given these huge numbers, crime is low," a spokesperson said.

In fact, over the past three years on average 730 arrests were made by Met police officers at carnival – a figure particularly low for an event of its size.

Just like the mas performers, the Met said its own planning for this year's event "began as soon as last year’s event ended" to ensure the safety of the million-plus people who now attend.

The Met will also be trialling a new facial recognition system, involving the use of overt cameras to scan the faces of passers-by. It flags potential matches against a database of custody images, populated with images of individuals who are forbidden from attending carnival, as well as those wanted by police who may attend carnival to commit offences.

The force said its "super-recognisers" – highly skilled officers who can recall offenders’ faces after seeing them briefly either in person or on file – will be monitoring CCTV from a control room to identify any known troublemakers.

"Carnival, in my opinion, was a struggle to make sure our culture was prominent in this country," Kenlock said. "That the wider society would accept us for what we are, and that's why we are determined that it shouldn't be stopped and it should be part of society."

But while the music and the floats may demonstrate Caribbean influence, Kenlock believes the event is losing its original roots as it becomes a more multicultural event.

“It has become very sanitised now and so we don't know which direction it is going in," he said. "In my opinion, it has been taken over by lots of different groups of people... It's a truly multicultural activity now, and I think it may reflect the society to some extent."

Kenlock's sentiment rings true for Giles Moberly, a freelance photographer who has captured the event over two decades and attended his first carnival in the late '70s. "The carnival feels a bit more commercial these days and more mixed," he said. "It's always positive, people are friendly and if you like dancing, loud music, and eating good food then go, you won't regret it."

Fears for carnival's future heightened this year when fresh rumours of a move to Hyde Park started circulating again.

Mayers, who attends carnivals all over the world, told BuzzFeed News that such a move wouldn't make sense. "Once you take it to a park, it then becomes a festival," she said. "But it's not a festival, carnival is a street parade. There are thousands of people that come on the bank holiday to support it... Moving it to Hyde Park would then take away its identity and what it actually means."

However, Alleyne-De Gazon said that making use of Hyde Park could be a good investment for both the organisers and the London boroughs.

"Everyone makes money off of carnival except the organisers," she said.

Alleyne-De Gazon believed it was a common misconception that the borough of Kensington and Chelsea, where Notting Hill is situated, makes money from the carnival. "They spend more money, just as the Met police would spend more money," she said.

In 2015, Stephen Greenhalgh, then deputy London mayor for policing, said "drastic cuts" to the Met's budget meant the two days of parades put a strain on London's police force.

This year the force is expected to spend between £6 million and £10 million policing the event, with up to 7,000 officers patrolling the streets throughout the August bank holiday weekend.

Although the cost might seem like a lot, it's not much compared with the £93 million the event is estimated to contribute to London’s economy each year.

The people who do make money from carnival, Alleyne-De Gazon said, are the pubs, nightclubs, and people selling food and drink at the event.

Alleyne-De Gazon said that Hyde Park was simply a suggestion, and one never intended to take the carnival off the streets. "There's no way you can pile a million people and more in Hyde Park, you’d destroy the park."

She said the procession would have to become longer, and the park would be used as a “haven” for those who do not particularly like crowds – people could instead pay to sit on the grass, have picnics, and watch performances if they didn’t want to walk around, for example.

"You could create a carnival village," she continued, adding that it could be used as an investment for the event.

But despite the concerns for carnival's future a spokesperson for London mayor Sadiq Khan told BuzzFeed News he is a "strong supporter" of the annual street parade.

"The event is a fantastic celebration of London’s different cultures and communities, which is enjoyed every year by hundreds of thousands of Londoners and tourists," the spokesperson said.

"It’s a vital fixture on the capital’s cultural calendar. And the mayor’s team are working closely with organisers, the Met, and others to ensure a safe and smooth event."