“It’s an abomination. It’s an embarrassment.”

The words of Coralee Smith, whose mentally ill daughter was found dead in a segregation cell seven years earlier, hung in heavy contrast to those of government officials on Dec. 11, 2014.

“They didn’t do anything,” she told the Globe and Mail. “I don’t know how they have the nerve to publish that drivel.”

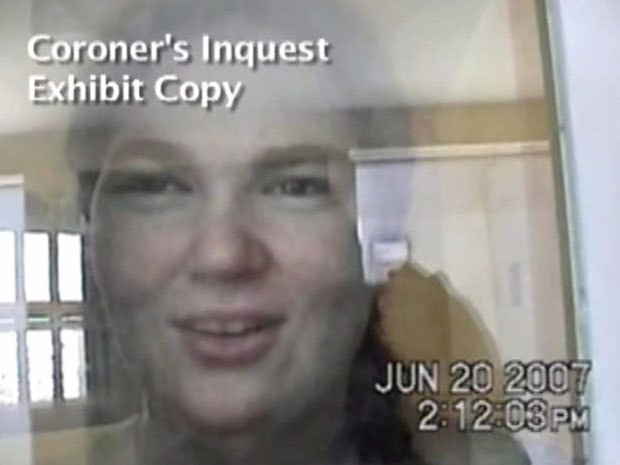

The Correctional Service of Canada had just released its official response to recommendations made by the jury of the coroner's inquest into the death — ruled a homicide — of 19-year-old Ashley Smith.

The federal prison service declared that it would not place limits on the use of segregation, citing a risk to prison safety.

The backlash was swift: Prison advocacy groups expressed outrage, while editorials poured in urging the correctional service to change course. Government officials remained mostly silent, refusing interview requests from media.

To this day, CSC maintains it has implemented “more than half of the recommendations or their intent.”

But documents obtained by BuzzFeed Canada reveal for the first time that the federal prison watchdog repeatedly warned the government its response was inadequate. His concerns were often met with resistance, and the final product was so lacking that he's considering giving up on formally monitoring CSC's progress.

“The response fell short of expectations," Howard Sapers, Canada's correctional investigator, said in an interview. "I think...it was tone-deaf as well to the seriousness of the issues that were being raised.”

“Instead, what was really managed was how the messages were going to be presented," Sapers said. "The ultimate report was, as I said, I just don’t think reflected the seriousness of some of the issues.”

"Stakeholder expectations will be raised"

Ashley Smith died of self-strangulation at Grand Valley Institution near Kitchener, Ont., in 2007 as prison guards watched from outside her segregation cell. They had been ordered not to intervene.

In the year before her death, Smith was transferred between prisons 17 times. She had a severe personality disorder, a prison psychiatrist testified at her inquest.

In 2013, coroner’s inquest jurors made 104 recommendations, including limiting segregation to a maximum of 15 straight days, providing 24-hour prison nursing services, and ending the use of restraints — all three of which are outstanding. The government was given one year to respond.

As part of the recommendations, Sapers’ office was asked to monitor the development and implementation of the government’s response.

Two days before the response was released, Sapers met with Public Safety Minister Steven Blaney; Don Head, commissioner of the Correctional Service of Canada; and other government officials to review the final document.

Briefing notes prepared for Sapers before the meeting reveal that he and his office predicted the public backlash.

“The Ashley Smith case continues to generate an unusually high (and sustainable) degree of public and media interest,” reads the briefing note, obtained through access to information laws.

“Stakeholder expectations will be raised and they will not likely be met by a response that relies on rehashing previous investments and commitments that are seven years removed from Ashley’s death.”

Neither Sapers nor CSC would divulge exactly what was said during the meeting. Sapers would only say that “it was an open discussion” and that those in the room were “fully engaged.” Blaney's office did not respond to a request for comment, saying it stood by CSC's comments.

But a follow-up letter to Blaney and Head obtained by BuzzFeed Canada reveals some of the the concerns Sapers shared during the meeting, noting that reaction to the response had been “overwhelmingly negative.”

“My own assessment, as I shared with you during our December 9, 2014 meeting, is that the response misses the mark,” said the letter, dated Dec. 30, 2014. “As a summary of process improvements that have been made since Ashley’s death, the response is largely retrospective and backward-looking."

Those at the meeting agreed with some of his critiques and made small changes to the document as a result, Sapers said. “I can’t tell you what was altered, but I can tell you there were some changes made to the content.”

Still, even with the changes, he wrote that few of the recommendations were “addressed with clarity or conviction” in the final version of the response.

Sapers said the final 55-page response contained about a dozen new initiatives.

View this video on YouTube

Ashley Smith is tied to a Prostraint chair at the Nova Institution in Truro, Nova Scotia.

Sapers ended the letter by listing some of the "outstanding recommendations" from the inquest and his office, such as limiting the use of segregation for mentally ill offenders.

“Movement on these issues would demonstrate that the lessons from Ashley’s tragic and preventable death have indeed been learned and, more importantly, acted upon,” Sapers concluded.

CSC spokesperson Véronique Rioux said in an email that all "options for potentially implementing" recommendations from Sapers' office "are rigorously explored before a response is provided." She said Head responded to the letter in February.

Sapers said the response contained a "summary of 13 commitments," and that his office is still looking for "updates and clarifications."

"Progress has been slow," he added.

They appear "to have squandered an opportunity"

The briefing notes written for Sapers before the Dec. 9 meeting with government officials also offer a glimpse into the year-long process that led to the government's final response.

"CSC (and the Government) have appeared to have squandered an opportunity to announce and implement much-needed reforms in the treatment and management of mentally disordered people in prison," the briefing notes read.

The government's public response to the inquest actually began on May 1, 2014, when Blaney announced CSC was launching a two-bed pilot project with the Brockville Mental Health Centre in Ontario to transfer severely mentally ill offenders who, by the minister's own admission, did not belong in prison.

"The Government of Canada recognizes the growing impact of mental health needs on the federal offender population," a statement read at the time. "This is just one aspect of the ongoing response to the recommendations of the jury from the Coroner's Inquest into the tragic death of Ashley Smith."

Sapers said he finds it "curious" that the response began as a "Government of Canada" one, then morphed into one borne by CSC alone.

The final response was crafted by those in the highest echelons of Public Safety Canada: a group of assistant deputy ministers managed by a steering committee composed of Head and deputy ministers from Public Safety Canada, the Department of Justice, Health Canada, and the Parole Board of Canada.

Sapers was frustrated by the format of the response, which changed drastically about halfway through the process. The working group had initially been using a grid to track the jury's recommendations and CSC's response to each one.

The grid was shared with Sapers' office a handful of times and met with strong criticism on each occasion. But the grid was abandoned in the summer of 2014, Sapers said, and replaced with a response that used themes to respond more broadly to the jury recommendations.

“The unusual format and ambiguous wording are among the most unfortunate and frustrating aspects of this response,” Sapers wrote in the Dec. 30 letter. “These features make it very difficult to determine which of the recommendations are accepted and supported versus those that have been rejected.”

CSC refutes this, saying it has listed the jury recommendation numbers next to the corresponding themes it used to structure the response.

But Sapers said he still doesn't understand some of what CSC wrote. "The language I find a little unusual," he said. "Like I really don’t know what 'Segregation Renewal' is. That’s a strange phrase to me.”

Moreover, despite promises to the contrary, Sapers' office was largely kept in the dark about the group's progress.

"The frequency of meetings, degree of engagement, circulation and consideration of working documents, as well as the direction given or received at these two levels, is unclear," Sapers' briefing notes said, adding, however, that a "one-day stakeholder's meeting" happened in early October.

Sapers said he was "disappointed as the process unfolded" because of the infrequency of his meetings with both Head and the deputy minister of public safety. He said the three had only one meeting over the course of the year that dealt strictly with the government's response to the inquest.

“I had higher expectations than that," Sapers said, adding that meetings at the working level were too infrequent as well. "And participation in those meetings was not as robust as I would have hoped.”

"It didn't really demonstrate learning"

The final product of a year's worth of work was mostly a re-telling of what CSC officials testified during the inquest, Sapers said.

"It didn’t really demonstrate learning. If wisdom is being able to demonstrate that you’ve learned from your mistakes, then CSC did not demonstrate that it is a very wise organization in terms of that report."

The response fell “so short of expectations,” Sapers wrote in the December letter, that his office might not keep monitoring on CSC’s progress in implementing its responses to the recommendations. Sapers, who was told this year he won't be re-appointed as correctional investigator, said he is still weighing his options.

Despite this, Sapers said he believes the government took responding to the inquest seriously. "But I think what they took seriously was not what I was hoping they would take seriously.”

The working group focused on managing how the response would make the government look as opposed to the "more aggressive change” needed to prevent similar deaths, Sapers said.

“The curious thing is, the Correctional Service of Canada does a lot of things really well and they’ve made some important improvements in how they do their business since Ashley Smith died," Sapers said.

For instance, the number of days spent in segregation no longer resets when an inmate is transferred. This was an issue for Smith: Every time she was moved to a new prison, her number of days spent in segregation was reset to zero. As a result, she didn't receive some of the psychiatric and administrative reviews mandated for long periods in segregation.

"They have not done a really good job of telling people about all that, and they continue to be defensive if you point out opportunities for improvement, and that’s very frustrating," Sapers said. "Why they’re like that, I don’t know.”

Meanwhile, the use of segregation is on the rise, and mentally ill offenders with striking similarities to Smith keep moving through the system.

Sapers, who said he's still in talks with CSC about the recommendations that haven't been accepted or implemented, argues the rules around segregation could be tightened and the correctional service could still safely operate.

“You could have a prohibition about segregating those at significant risk of self-injury or suicide," Sapers said, "and CSC could still safely operate and manage every penitentiary in Canada."