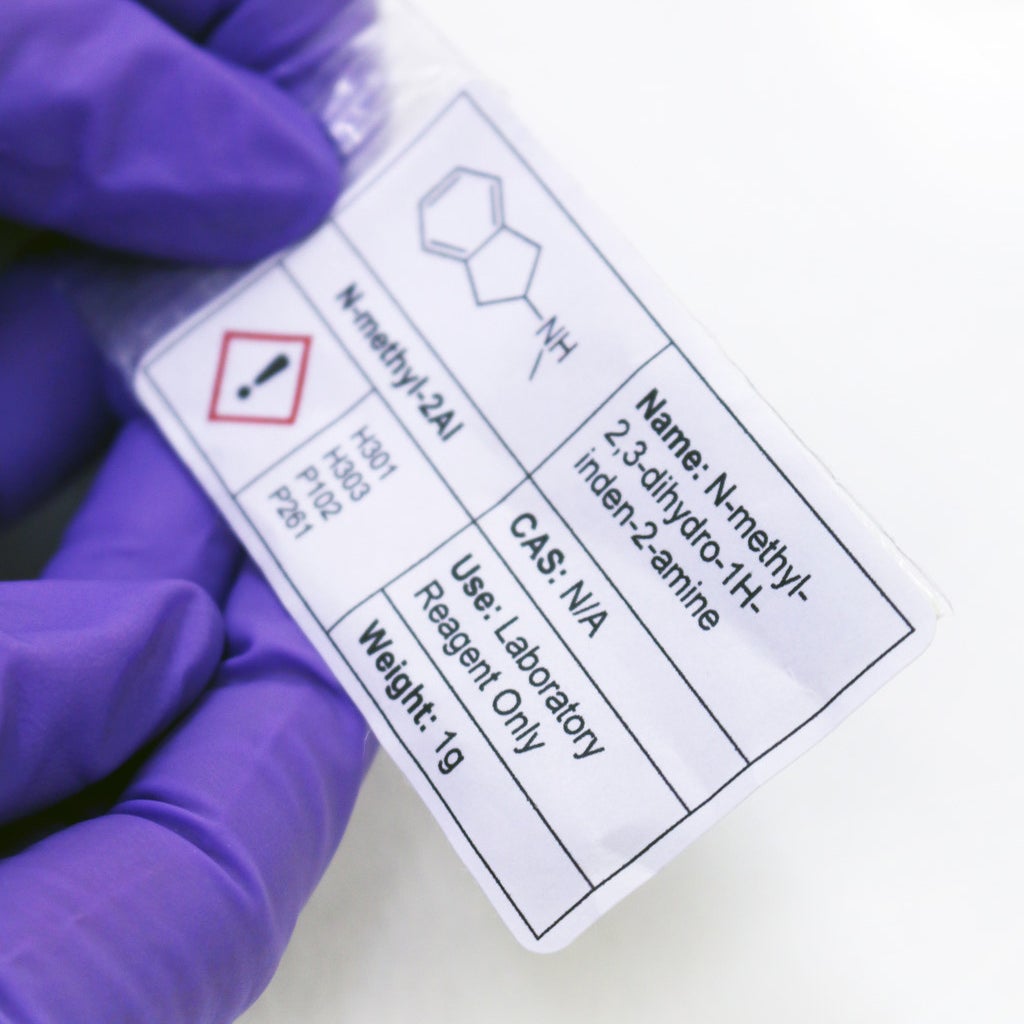

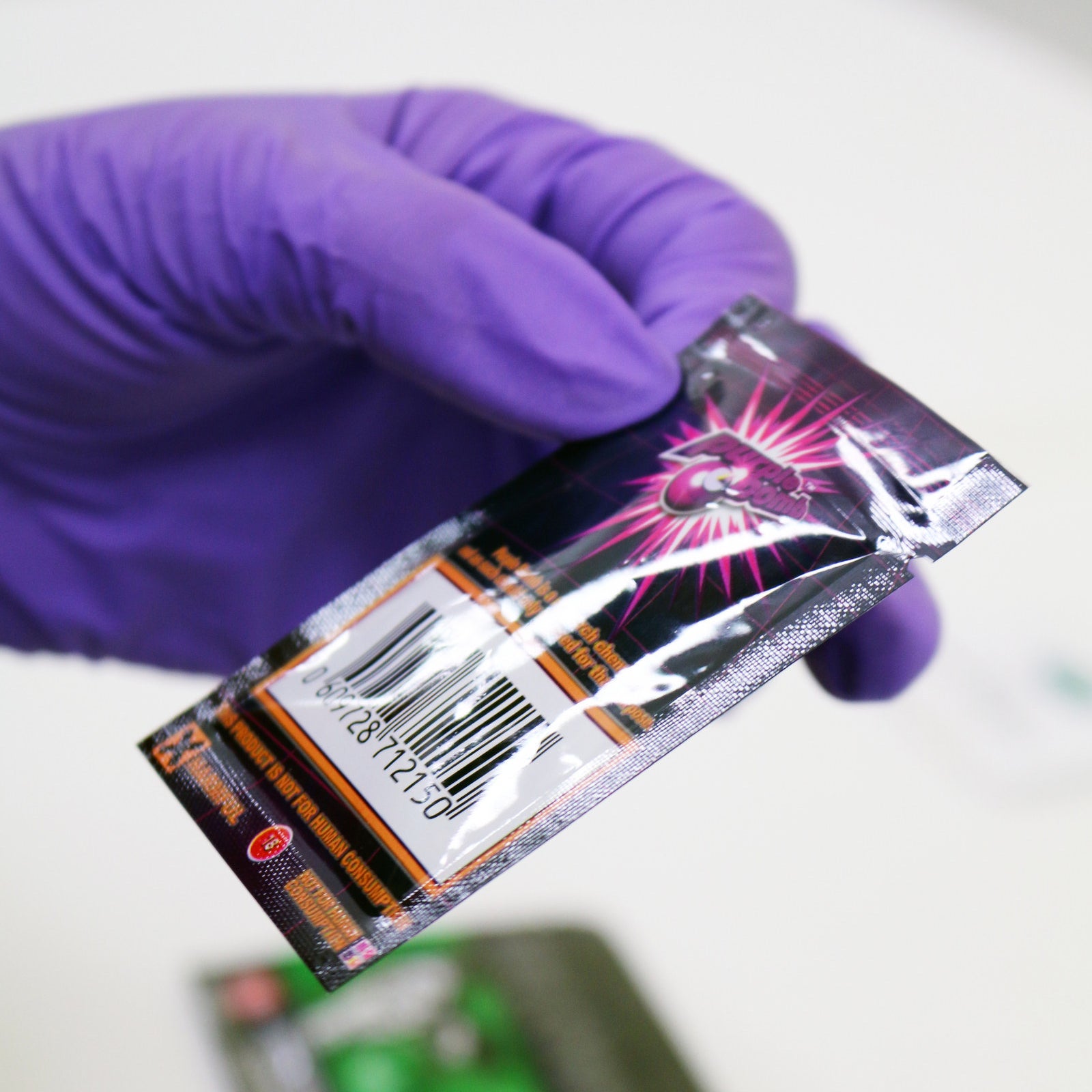

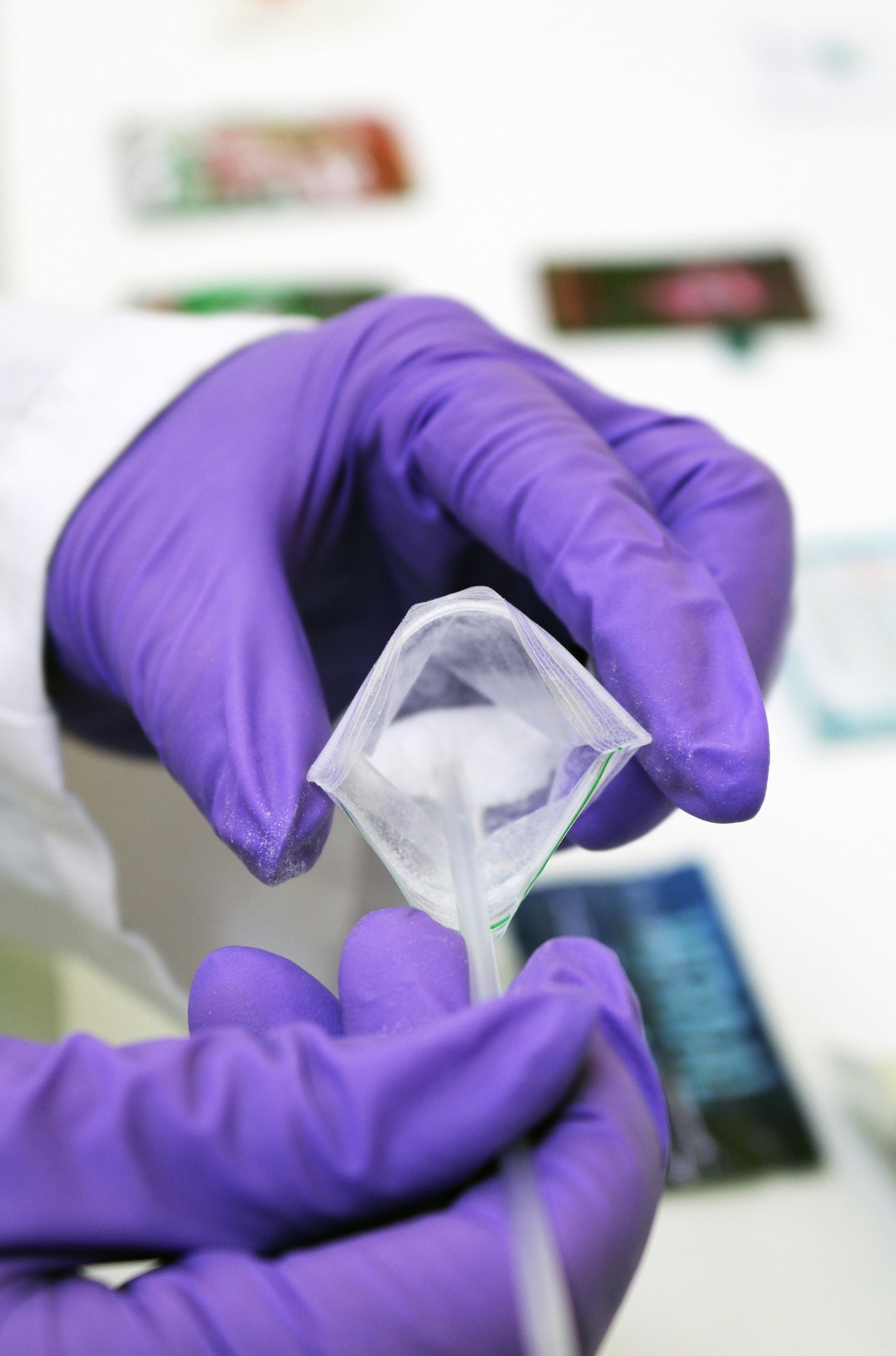

"You’ve absolutely no idea what you’re getting with these things," government scientist Audrey Smith says as she taps out some powder from a small glossy packet. “Even within the same head shop [a store selling drug paraphernalia], the same packets contain different things. The main drug they’re advertising tends to be in there, but there’ll be a couple of other drugs, some cutting agents. We see some utterly random things that I don’t know are meant to be in there or are in there by accident."

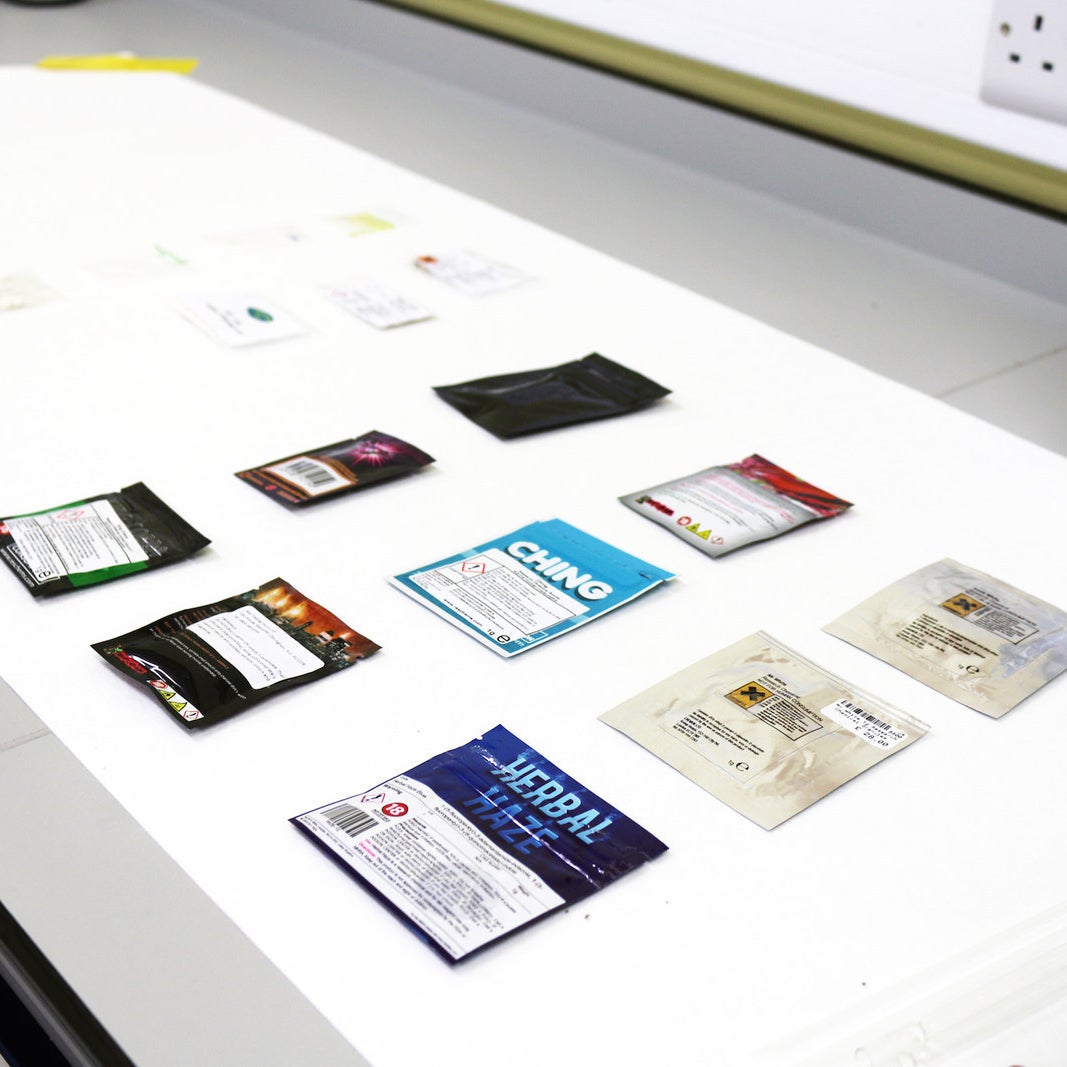

The packs are emblazoned with eye-catching names – King Cobra, Herbal Haze, Purple Bomb, Mr White – and most have stark warnings on the front: “Not fit for human consumption.” In reality, of course, that’s exactly why these legal highs have been created. They make money for both the chemists who cook them up – mainly in China – and the distribution chain closer to home.

BuzzFeed News has been invited to the Home Office’s Centre for Applied Science and Technology (CAST), a group of eerily quiet buildings surrounded by fields in St Albans, Hertfordshire. This is where Smith and her team test the “new psychoactive substances" (NPS) – otherwise known as legal highs – found at festivals, clubs, and shops. She is project manager of the government's Forensic Early Warning System, which was set up in 2010 to help tackle a rise in the use of legal highs across Britain.

The small group of scientists sit at computer screens monitoring the chemical compounds that make up these substances. Tapping out a small amount of powder on to one machine, Smith is able to tell us its main components in under 30 seconds by looking at a graph on the connected laptop. This portable testing machine, which is taken to festivals for on-the-spot tests, analyses how infrared light interacts with molecules. Each substance has its own unique infrared spectrum, similar to a human fingerprint. A huge whirring machine at the back of the lab is able to conduct longer, more accurate analyses.

Legal highs have been designed by savvy chemists to mimic the effects of illegal drugs such as cocaine, ecstasy, and cannabis. The problem the government faces is that as soon as the synthetic substance is identified and banned, chemists in China, Pakistan and India tweak it slightly to take it back outside the law. More than 500 legal highs have been outlawed since 2010 – but more and more keep popping up regardless.

The government has decided that it's fed up of this this cat-and-mouse game and has announced plans to introduce a blanket ban on all psychoactive substances; that is, anything that affects the human brain. It includes nitrous oxide (or laughing gas), a festival favourite, which could carry a seven-year sentence for those caught selling it.

But critics have warned that the new psychoactive substances bill – currently going through parliament – is so ambiguously worded it could be unworkable. As drafted, it effectively means that any substance that alters your mood would be illegal. Exceptions such as medicines, alcohol, nicotine, caffeine, and chocolate have had to be spelled out.

Some campaigners also worry that the ban will simply see the legal highs industry driven underground. The EU's drug agency warned last month that the trade would simply move into “grey marketplaces” on the hidden web only accessible via encryption software.

The government insists a blanket ban is the best way to prevent more deaths and keep young people safe. Dozens of fatalities in the UK have been linked to legal highs in recent years, and last week 18-year-old Ally Calvert died after apparently inhaling nitrous oxide at a London house party. But ministers stand accused of using dubious statistics to inflate the number of deaths caused by the substances.

Smith said many users were unaware of just how strong a legal high could be. "You’ve absolutely no idea what you’re getting because they’re so new,” she said. "No idea on the dose and the strength, how safe to take it is. It’s just a lottery – there’s no way of knowing what you’re taking and what effects it has on the body, even if you’re used to taking drugs."

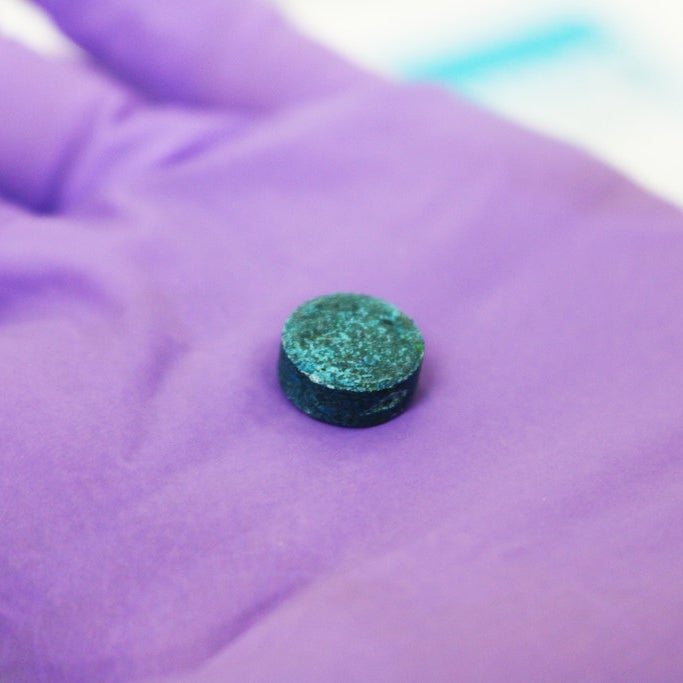

The small foil packages sold in head shops and behind the counters of some newsagents are designed to look commercial, and the backs are covered with lists of ingredients in tiny type. Some contain white powders, others green pellets. Most brand themselves as “harmful”. But a quick Google search of the products’ names gives you a rundown of what drug they are designed to emulate. King Cobra is a “synthetic aromatic incense formulated from synthetic canaboids”, according to one online legal high store.

Cocaine substitute Ching is “one of the most popular research chemical compounds”, according to a site with reviews of new substances that drift into self-parody: "Oooffftt this bad boy stings like mad but hits the spot like a left hook from tyson....Afterwards your left kinda floating around. Swinging from tree to tree til you're ready to go again.”

Smith pointed out that not every legal high does what it purports to do – and that the reality can be incredibly dangerous. "Some of the stimulants sold as mimicking ecstasy will have hallucinogenic effects,” she said. "So you think you’re taking a legal version of ecstasy and suddenly you start hallucinating. And synthetic cannabis, or cannaboids, can be 100 times stronger than cannabis and people don’t know how much to take, especially when it’s in that powder form."

Analysis of legal highs has turned up some very random ingredients that aren’t listed on the packets, such as anti-malarial drugs. "You think, Is that in there for a specific purpose?” Smith said. "We’ve done festivals in the past and have seen tablets with six or seven different compounds in them; some will take you up and some will take you back down. It’s not like been engineered so that you get the high and then you get the antidepressant, there’s absolutely no way it works like that, so why would you put this mixture of things together?"

Smith doesn’t deny that a ban might push legal highs underground. But she insists that closing down head shops will help save lives. "If it’s right next to you and you can legally go in and buy it, it’s much more accessible,” she says. "If you have a substance that's causing harm and it becomes controlled, at least the police can actually take action.”

But it's virtually impossible to know just how dangerous legal highs actually are. Research from the Centre for Social Justice, a think tank, found there were 97 recorded deaths linked to legal highs in the UK in 2012: almost two a week. These figures formed a key part of the government's push to ban such substances but have been strongly criticised for exaggerating the scale of the issue, while other drugs and alcohol are likely to have contributed to many fatalities. Smith said it was notoriously difficult to prove a person had died after taking a legal high because the substance starts to "metabolise" or break down almost immediately.

"The metabolites of your traditional drugs – cocaine, heroin – these are well understood, they [pathologists] know what they’re looking for,” she said. “But trying to understand the metabolic pathways of some of these, where do you even start? So unless there’s very strong evidence, like they’re holding the packet in their hand or they have it on them, it can be difficult to know what that original cause of death was."

Professor David Nutt of Imperial College, a former government drugs adviser, believes that legal highs have caused far fewer deaths than has been claimed. He told BuzzFeed News the bill was "unnecessary", saying: "Its main rationale is to close 'head shops', which can be done easily using existing legislation, and this blanket ban will probably increase use of 'harder' more dangerous drugs.

"Moreover, banning all current and future psychoactive substances even if harmless is anti-scientific and could seriously damage UK neuroscience research and medical innovation."

But Maryon Stewart, founder of the Angelus Foundation, a charity that highlights the risks of legal highs, welcomed the blanket ban. "We expect the law to impact very significantly on the high street trade," she said. "The open sale of NPS has led to dangerous experimentation, with many young people being badly affected by their unpredictable effects and some ending up in hospital.

"Sadly, too many have paid the ultimate price from taking these risky substances and this change will go a long way to stop further deaths."