Creating more grammar schools will not boost overall education standards or improve social mobility – in fact it could just make the gap between rich and poor children even worse, a damning report has found.

The Education Policy Institute (EPI) think tank warned against the move after carrying out what it claimed to be the most detailed study of government data on selective schools for almost a decade.

Labour banned new grammars in 1998 amid concerns they were dominated by middle-class children and failed to help the poorest in society – but prime minister Theresa May has unveiled plans to overturn this ban.

The government has insisted it isn't harking back to the past and that grammars would need to boost their intake of pupils from poorer backgrounds. But the plan still faces opposition from Labour and some Conservatives, including former education secretary Nicky Morgan.

In a report out on Friday, the EPI said creating new grammar schools – which require pupils to sit an entrance exam known as the 11-plus – was unlikely to lead to "either a significant improvement in overall education standards or an increase in social mobility".

David Laws, the think tank's chair and a former Liberal Democrat schools minister, said: "Indeed, without far more success in getting poor children into grammar schools, the total attainment gaps between poor children and richer children could well increase.

"Quite simply, there are far too few children from lower-income families who attend grammar schools – and although these schools generally deliver good results for their pupils, the attainment gap widens because it is not those from disadvantaged backgrounds who benefit."

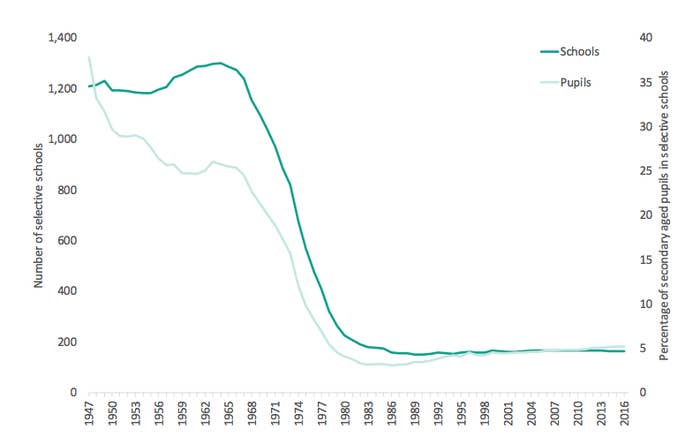

There are currently 163 wholly selective state-funded schools in England, according to the report. Around 170,000 pupils attend selective schools, representing 5.2% of all secondary-aged pupils in state education.

The graph above shows that the number of selective schools – and the proportion of pupils that attend them – has fallen dramatically since the closure of most grammars in the 1970s and early 1980s.

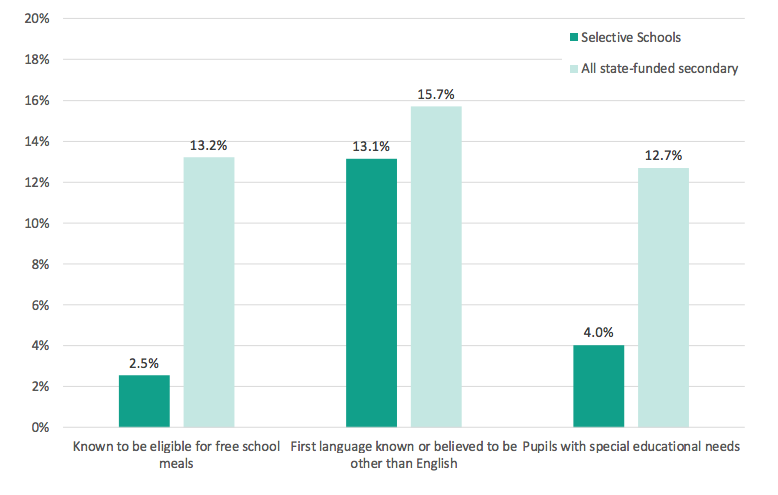

Selective schools are now found in just 36 of the 152 local authorities in England, with the highest concentrations of pupils in Trafford and Buckinghamshire. And grammar school pupils "differ strikingly from the population of all

secondary-aged pupils", the EPI found. This graph below shows how they compare.

For a start, pupils who attend selective schools are far less likely to be from deprived backgrounds – only 2.5% of them are eligible for free school meals compared with 13.2% across all state secondary schools.

Selective school pupils are also less likely to have a first language other than English (13.1% compared with 15.7%) and far less likely to have special educational needs (4% compared with 12.7%).

This is because pupils with these characteristics are less likely to pass the 11-plus entrance test, the report said. The so-called "attainment gap" between them and their peers is set in motion years earlier, when children are toddlers.

"If considering grammar schools as a policy to increase social mobility, there are significant gaps in attainment by age 11 that an expansion of grammar schools cannot address," the report said.

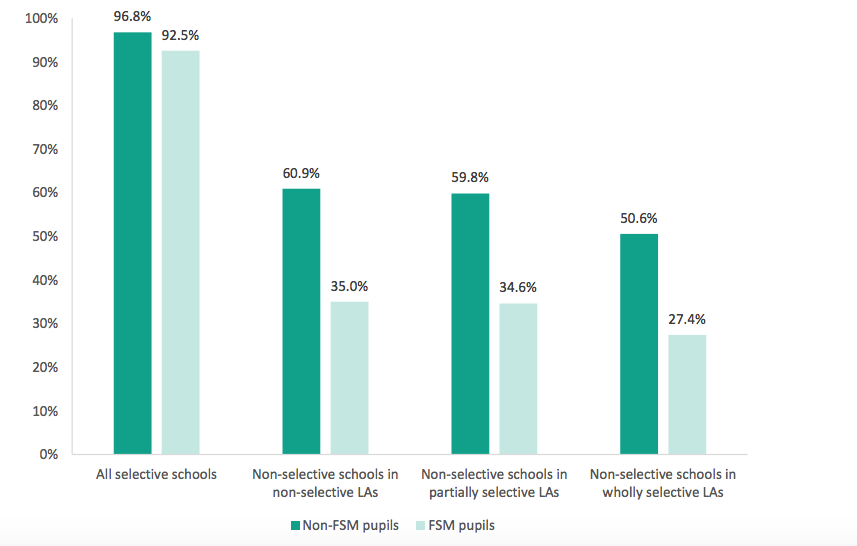

But the prime minister has insisted that grammar schools are in fact better than other schools at boosting the grades of the poorest pupils. She told the House of Commons last week that the attainment gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged pupils was "virtually zero" in grammars.

The graph above does indeed show that the gap is smallest for selective schools – with 92.5% of pupils on free school meals (FSM) getting at least five A* to C grades at GCSE, compared with 96.8% of other pupils.

That 4% gap contrasts with a gap of more than 25% among pupils in non-selective schools in non-selective local authorities.

But the report said May had not accounted for the fact that grammar schools were drawing their intake from a "narrow prior attainment band" – in other words, the disadvantaged children at grammars achieving decent GSCEs were already doing well at primary school.

"In selective schools we are comparing FSM pupils with high prior attainment to non-FSM pupils with high prior attainment," it said. "In non-selective schools we are

comparing FSM pupils from across the prior attainment range to non-FSM pupils from across the prior attainment range."

The think tank said that instead of expanding grammar schools, boosting the number of decent comprehensives could be the answer. There are

five times as many "high quality" non-selective schools as there are grammars, according to the report.

These are far more socially representative than grammars, with higher proportions of poorer pupils and those with special educational needs. The report found there was "no benefit" for high-attaining pupils in attending a grammar rather than one of these high-quality non-selective schools.

Laws said: “On the basis of our analysis, there have been far more promising recent interventions to boost social mobility – for example, the early academies programme saw bigger attainment gains for children from poor backgrounds.

"And this first generation of sponsored academies are now helping to educate around 50,000 children on free school meals, as against a mere 4,000 in grammar schools.

“The government says, of course, that it wants grammar schools to take more pupils from lower-income backgrounds – but it is far from clear how this would be achieved in practice."

A Department for Education spokesperson said: "Our proposals are not about recreating the binary system of the past, which is what this report is based on.

"Our new approach would ensure any new selective schools prioritise the admission of pupils from lower income households or support other local pupils in non-selective schools to help raise standards."