Prime minister Theresa May has recalled her cabinet from their Easter break for an emergency meeting to discuss possible military action against Syria, amid mounting speculation that she will authorise an attack without a vote in parliament.

A number of senior MPs, including Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn and Julian Lewis, the Tory chair of the defence select committee, have expressed deep concern at the prospect of any attempt by May to bypass the House of Commons.

Cabinet ministers are widely expected to rubber-stamp British involvement in a coordinated military intervention in Syria in a meeting on Thursday afternoon, following a suspected chemical weapons attack that the World Health Organization said killed more than 70 civilians and injured another 500, in a suburb of Damascus.

Corbyn told BuzzFeed News on Thursday that a Commons vote should be tabled before any military action. He said May's government appeared to be ignoring parliament "by not recalling parliament when it could have done, and taking a decision in the cabinet apparently today, which if Donald Trump's tweets are anything to go by could be implemented very quickly."

But does the PM actually need to consult parliament before ordering military action? Has that always happened in the past? Here's what you need to know.

The decision in 2003 to allow parliament a vote on the Iraq invasion has set a convention by which MPs are consulted before any military action. But, crucially, the government has no legal obligation to do this.

Deploying the armed forces is currently a royal prerogative power, meaning the PM is free to act without a vote in parliament. Decisions are taken within the cabinet, with advice from the chief of the defence staff – the head of the armed force – and other military and intelligence officials.

So the government is under no legal obligation to keep parliament informed, according to the House of Commons library. But since 2003 the convention has been to give MPs a say before UK troops are deployed.

MPs approved the decision to go to war in Iraq but they were not explicitly given a vote on previous military action in Sierra Leone, Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan, and the Falklands.

Shortly after becoming prime minister in 2007, Gordon Brown proposed that the royal prerogative should be reformed so that governments must seek the approval of the Commons for "significant, non-routine deployment of the armed forces into armed conflict".

A green paper titled The Governance of Britain declared that the prerogative power was an "outdated state of affairs in a modern democracy".

"On an issue of such fundamental importance to the nation, the government should seek the approval of the representatives of the people in the House of Commons for significant, non-routine deployments of the Armed Forces into armed conflict, to the greatest extent possible," it said.

But the proposals were never implemented before Labour was voted out of power in 2010.

Then the Conservatives pledged to look at the issue as well, promising to give parliament a bigger say on military action.

The Conservatives' 2010 manifesto promised to make "the use of the royal prerogative subject to greater democratic control so that parliament is properly involved in all big national decisions".

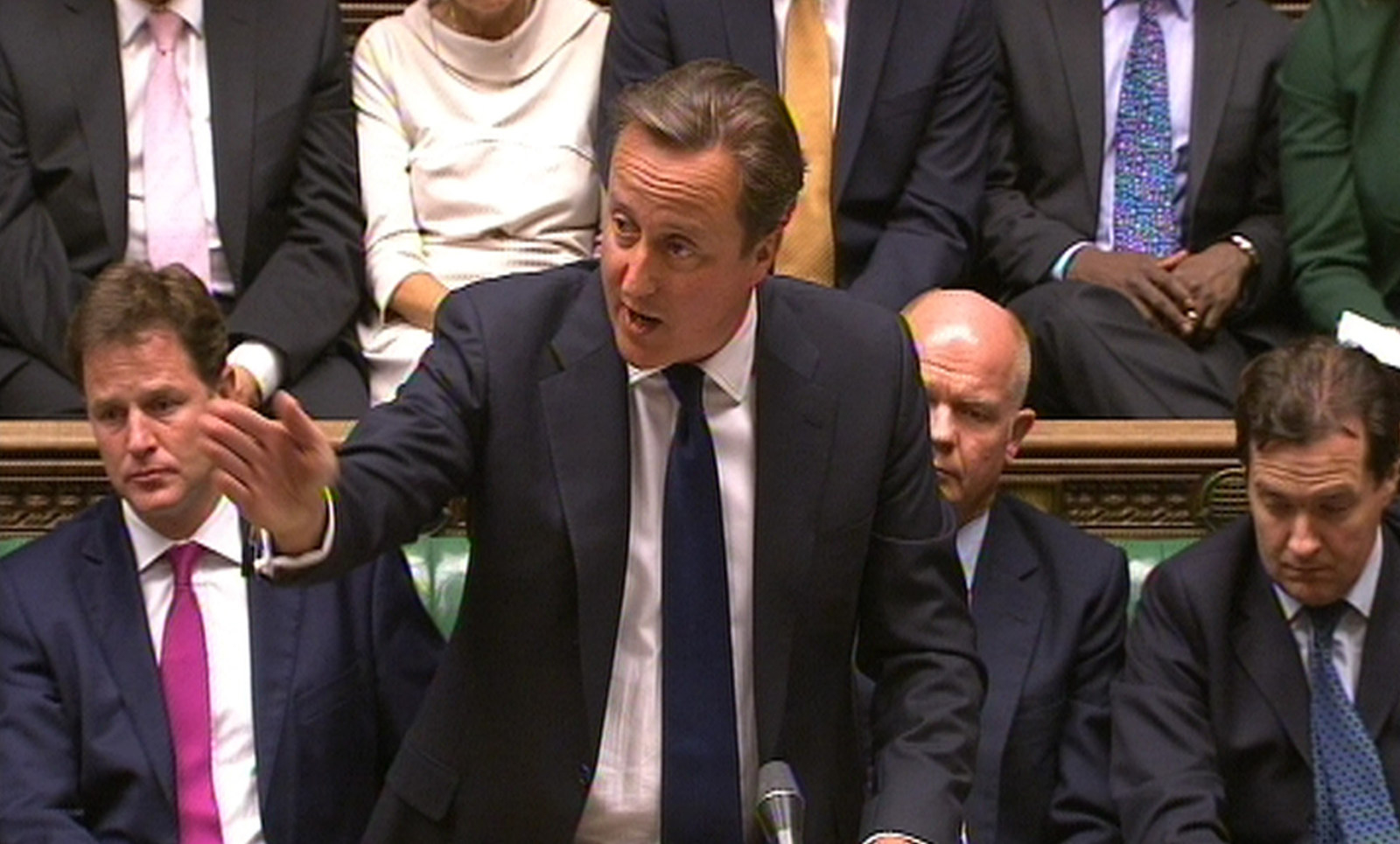

But there was no such pledge in the coalition agreement with the Liberal Democrats (despite their backing for the reform). And although PM David Cameron did give MPs a vote on plans for British forces to enforce a no-fly zone over Libya in 2011, there was some consternation that the vote had happened one day after the UK's first strikes.

British troops were then deployed to Mali in 2013 – with no vote in the House of Commons.

The government deployed more than 300 military personnel to West Africa to support French forces against Islamist rebels, but there was no debate or vote on this.

That sparked some concern from MPs about ministers' previous assurances that the convention for a formal vote would be respected.

Jeremy Corbyn, then a Labour backbencher, argued that it was "now the norm in parliament that the significant deployment of British troops in a war requires the consent of parliament".

But ministers insisted that UK troops were not engaged in combat and therefore the convention did not apply.

Cameron did order MPs back from their summer break in August 2013 to seek approval for military action against Syrian president Bashar al-Assad following a suspected chemical weapons attack. He lost by 13 votes.

Cameron said he would respect the defeat by 285 to 272 votes. This was widely seen as a key moment in the long-running debate over the power of parliament on matters of military action.

Many commentators suggested that any future significant deployment of UK armed forces would now be "inconceivable" without first going to the Commons.

MPs were later given a vote in September 2014 on military action against ISIS in Iraq, voting overwhelmingly to sanction air strikes.

Cameron went back to MPs in December 2015 to ask for support for air strikes against ISIS in Syria. He won by 397 votes to 223.

The PM said afterwards that the Commons had "taken the right decision to keep the country safe".

The House of Commons library believes the Syria vote in 2013 was a turning point and that the government's defeat "laid to rest" the existence of the convention once and for all.

However, it remains the case that parliament has no ~legally~ established role in approving the deployment of UK troops. Some MPs would urgently like to see the convention placed on a statutory footing.

Tory MP Julian Lewis, chair of the defence select committee, is among those who are calling on May to come to parliament before deciding on possible military action in Syria.

"When we are contemplating military intervention in other people’s conflicts, parliament ought to be consulted," Lewis told MailOnline.

The SNP's Westminster leader Ian Blackford has added: "It’s a very dangerous step for the government to take action without having that consent of parliament and by extension the consent of the people of the country."

But the Tory chair of the foreign affairs committee, Tom Tugendhat, and the Tory chair of the health committee, Sarah Wollaston, have both said they would be happy for the PM to use the royal prerogative without consulting MPs.