Lately, I have developed the habit of ordering books deep into the night. This is, we might say, a form of drunk dialing, since I mainly do it when I’ve had a few. A couple of weeks ago, after a phone conversation with my father about George Orwell, I found myself, just shy of midnight, visiting Powell’s website, where I ordered two volumes of the author’s essays, Facing Unpleasant Facts and All Art Is Propaganda, for my old man. Then, I promptly forgot about it — until three or four days later, when my father called to thank me for the unexpected gift.

Drunk dialing. Can we even use the phrase in a culture where we are never dialing, although, it often appears, we must be constantly in touch? In his novel Slaughterhouse-Five, which I read for the first time in tandem with my father (I was 12 and he was 37, and if this suggests certain overlaps, that both is and is not the case), Kurt Vonnegut gives perhaps the finest explanation of the phenomenon. "I have this disease late at night sometimes," he writes, "involving alcohol and the telephone. I get drunk, and I drive my wife away with a breath like mustard gas and roses. And then, speaking gravely and elegantly into the telephone, I ask the telephone operators to connect me with this friend or that one, from whom I have not heard in years." For me, these friends are books, or maybe books are the machinery, or I am talking to myself. Either way, drinking can make us softer, more nostalgic, more impulsive, which is a mixed blessing, although in my case, it stirs an openness, a generosity, that sobriety does not allow.

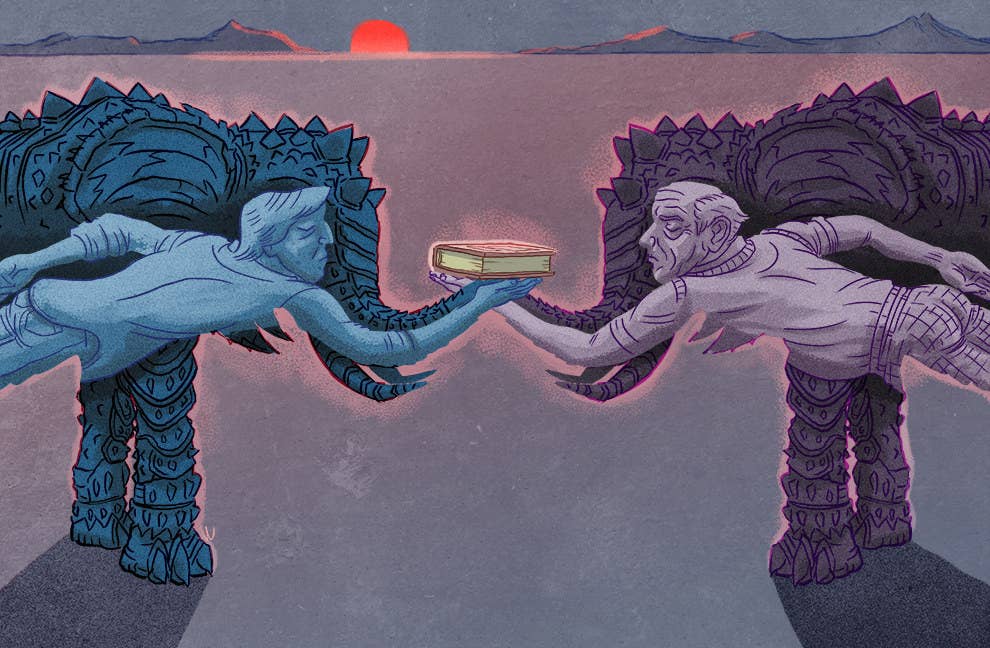

We wear our gruffness like an armored epidermis.

Take those Orwell books as a for-instance: I am not a gift-giver, not a commemorator of holidays. Phone calls, yes — no drunk dialing in those instances — but no cards, no flowers, nor would my father want or expect any such expression of my love. We wear our gruffness like an armored epidermis. We are both skeptical, or cynical, toward consumer culture and what it portends. We don’t often kiss or say "I love you"; this is not how I was raised. It’s one of the reasons I tell my own kids that I love them 20, 30, 40 times a day, as part of every interaction, every text or phone call, so often (I fear) it loses meaning, becomes as brusque or empty as not saying it at all. With my father, though…a quick hug, a few minutes on the phone, and the occasional smaller gesture, made more resonant for being an unexpected act of grace.

When he and my mother visited South Africa, he brought me back a two-volume paperback edition of Nelson Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom, although I could have found it without difficulty in the U.S. When they passed through San Francisco, he went to City Lights Bookstore and bought a selection of the Pocket Poets (Reality Sandwiches, Lunch Poems, Pictures of the Gone World), most of which I already had. It is not the utility of these gifts that moves me so much as the longing, the wish for some sort of connection, a matter of both heart and soul. My father is not someone who expresses his emotions; once, a decade or so ago, during a fight about who-even-remembers-what, I told him I was sorry I had hurt his feelings, and he responded, with no irony whatsoever, that he had no feelings I could hurt. I looked at him and laughed, but he wasn’t kidding. This is how he sees the world. These books, then, it is not important whether I possess or have read them, or can get them on my own. The old cliché applies: It’s the thought that counts.

Books are, have always been, a shared vernacular between us.

Books are, have always been, a shared vernacular between us. It’s in the pattern of our interactions; each conversation, after a few minutes of personal prologue ("How’s your son?" he’ll ask, to which I’ll answer, "Fine." Or: "Adrift." Or: "Let’s talk about something else"), and then he’s telling me what he’s been reading, mysteries usually, high-end crime, Donna Leon and Andrea Camilleri, neither of whose work I know. Sometimes, we’ll talk about a review he’s read — rarely one of mine, even when I’ve written about the book in question, even when I disagree with the assessment he is quoting back to me. What to make of that? I don’t know, except perhaps that I am not the writer he wishes I were. This is not a matter of recrimination, although at times it has been. This is not a matter of what I want or what I expect. I’m an adult, I can fend for myself, and I know my father loves me, even if it is not, exactly, in the way that I desire. And the truth is that I have come to keep my distance also, calling less, letting him get off the phone without much protest, relieved in some way when the conversations slides back to books.

In his essay “Return to Sender,” Mark Doty observes, "The lives of other people are unknowable. Period. I wouldn’t go as far as a poet colleague of mine who says that 'representation is murder,' but I would acknowledge that to represent is to maim." Doty is writing in part about his relationship with his father, who felt so betrayed by the poet’s memoir Firebird that he stopped speaking to his son for good. I don’t feel the same risk, partly because the issues between my father and me, our divisions, are not extreme enough — or, at least, not extreme enough to me. But what do I know? That could just be a story I am telling myself. Last Father’s Day, when I called my father, I mentioned that I had posted a photo of the two of us on Facebook, then joked that he should get an account so he could read what I had written about him. "You can say what you want about me," he responded, "you always have" — and for the briefest of moments, it was unclear to me whether he was expressing acknowledgement or lament. The instant passed, the instant always passes, it is what I have learned from all this living, that even the most freighted moment dissipates, and this was not that, in any case. And yet, the impression of it lingers, because I have no idea what he would think of being portrayed as I am doing here, what he would think of being exposed.

This, I want to say, is why we fall back on books, the two of us, individually and together. This is why we prefer to talk about ideas. This is why we shift from terra incognita to a world that is mapped and known, where we can pretend emotions are not an issue, that we don’t want anything from one another that we don’t already have. I think about that photograph I posted, taken at a brunch in my parents’ apartment the morning of their 50th anniversary party, in April 2008. In it, we are sitting together on a sofa in the living room, a piece of abstract art on the wall behind us, with a field of geometric shapes in yellow, blue, and red. That painting has hung there for longer than I can remember, so long I have stopped noticing it, wallpaper, set dressing, part of the display. So, too, the lamp on the side table with its crystal stem and linen shade, as well as the Meissen porcelain figurine beneath it, the female figure hunched forward, reading, like a symbol come to life. In the picture, I am smiling into the lens, while to my left, my father sits back, gazing past the frame. We look alike, we have always looked alike — or perhaps it is more accurate to say that I look as he did when he was my age, and he looks as I will when I am his. This, too, is part of our connection, our disconnection, the way that gazing at him is like staring into a convex mirror, through which I see more limits than possibilities. Limits — as in the limits of the body (his has fallen as mine is falling, thinning out around the chest and shoulders, gathering around the waistline, in the gut), as well as those of the soul, a kind of internal mechanics of distance, as embodied in his manner of sitting, backed into a corner, eyes flat and dispassionate, as if too reserved, too unemotional, to allow himself to be involved.

What I notice is the space between us. What I notice are the gaps.

I got 142 likes on that photo, and a single comment that read: "so beautiful!!!" I say this not out of self-satisfaction but reportage, so I can keep straight how it is. What I notice is the space between us. What I notice are the gaps. What I notice is that we are not looking at each other or touching in any way. And yet, it is also the case that we are occupying this space together, just the two of us, in uneasy symmetry. There are other photos from this party and the one that followed it, photos of us talking, with other people around. There is a sequence of me offering a toast that evening, with my father standing to my left, and my daughter, then 9 years old, underneath my arm. I remember that moment distinctly, talking to him as I clung to her. But it is this other photo to which I find myself drawn because it seems to tell me so much about who and how we are.

That toast I gave, not so many hours later… I had been drinking then, as well. Drunk dialing, but not really, since I was in control. I talked about my parents as having modeled a collaborative relationship, which is perhaps their legacy. My father and my mother, co-conspirators, a society of two, in many ways, which is also true of my wife and myself. Still, where is the place for children in such a dynamic? I wonder from both sides of the lens. How do we reach out, how do we find a middle ground? My father was surprised that I bought him those Orwell books; I could tell by his tone of voice. He was surprised that I had pushed the conversation to another level, that I had taken it to heart. I mentioned that I had written about them, but he didn’t ask for a link, nor did I offer to send him one. Part of growing up is that we no longer need our parents’ approval, although it’s nice to have. In any case, he is now reading Orwell, an essay at a time, and I look forward to discussing them, at some point, some evening perhaps when I call him after I have been drinking — not too much but just enough.

***

David L. Ulin is a 2015 Guggenheim Fellow, and the author, most recently, of Sidewalking: Coming to Terms With Los Angeles, a finalist for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. His novel Ear to the Ground, written with Paul Kolsby, is out now.

To learn more about Ear to the Ground, click here.