Early in May 2010, immigrant rights activist Oswaldo Cabrera announced that he was going on hunger strike.

Arizona had just passed its infamous bill targeting undocumented immigrants. Tens of thousands of people had recently gathered in Washington, D.C., to demand comprehensive immigration reform. Democrats, who controlled Congress at the time, were vowing to pass a reform bill, and activists around the country were convinced they could push them to do so.

Cabrera, a fixture in the Spanish-language press in Los Angeles, had recently moved to New York City. He had built a reputation as a tireless defender of the rights of the U.S.-citizen children of undocumented immigrants.

"I'm determined to arrive at the final consequences — death, if necessary," Cabrera told a camera crew from CNN En Español outside a church in East Harlem, demanding the repeal of the Arizona law and citizenship for America’s undocumented. “The system has to change.”

Cabrera would go on to say that the hunger strike lasted two months. "I nearly lost my kidney and my liver," Cabrera recently told BuzzFeed News. "And I did it with pleasure."

A few days after Cabrera announced the hunger strike, Luis Enrique Flores ran into him in Queens. The two men came from the same small province in Ecuador, and Flores had hired Cabrera to help him with his immigration case. Cabrera denies what happened next, but according to Flores, they dined together that night at an Ecuadorian restaurant on Roosevelt Avenue.

"We ate well," Flores said.

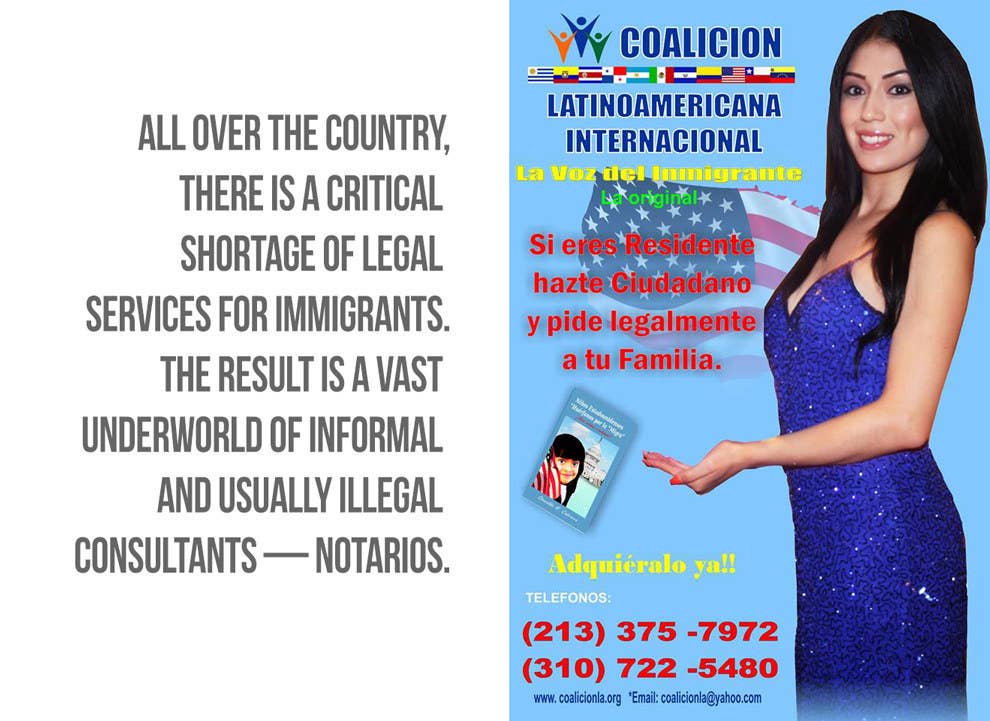

From the top floor of an office building in central Los Angeles, Cabrera runs the Coalición Latinoamericana Internacional, an organization that offers nearly every conceivable immigration-related service. On TV, on the radio, and in full-page ads in Spanish-language broadsheets, Cabrera says he will help make you and your family legal. Some of these ads claim he and the Coalición have won more than 250,000 immigration cases.

But Cabrera is not a lawyer. Instead, he styles himself an activist — a community leader and defender of immigrants’ rights. For more than a decade, Cabrera has reached an audience of millions, making frequent and steady appearances in every major Spanish-language television network and newspaper. At times he has managed to cross into English-language media, landing in the pages of the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times, among others.

All the while, Cabrera has used his reputation as an immigrants’ rights advocate to steer clients to his business, allegedly illegally charging them thousands of dollars to file paperwork with federal immigration authorities. On both coasts, he has left a trail of people who accuse him of misrepresenting his ability to take on their cases, swindling them out of what little savings they had, and failing to file any meaningful paperwork or do any real work on their behalf — leaving them in exactly the same legal situation as when they first walked through his door.

Now Cabrera stands accused of fraud in two lawsuits in California, and the lawyers who filed them say there are at least three others coming. The lawsuits accuse Cabrera of posing as a lawyer and charging people thousands in appointment after appointment.

The Los Angeles County Department of Consumer Affairs, which regularly collaborates with law enforcement, declined to release records about Cabrera, citing a pending investigation.

Cabrera’s operation is unusual in its flair, but he is hardly alone. Ever since President Barack Obama announced last November that he would protect millions of immigrants from deportation, advocates around the country have been sounding the alarms about scams by so-called notarios, a catch-all term for people who practice immigration law without a license, some of whom use their status in the community to ruthlessly exploit those seeking to navigate the U.S. immigration system.

Under U.S. law, only immigration attorneys and a small number of accredited non-lawyers are allowed to help immigrants seeking status with even the simplest of transactions, such as filling out and filing forms with the government. The American immigration system is extraordinarily complex, and every step of the way, the stakes are high — immigrants who submit false information to the government, knowingly or otherwise, can wind up deported.

Yet, all over the country, there is a critical shortage of legal services for immigrants. The result is a vast underworld of informal and usually illegal consultants — notarios.

In the U.S., a notary public does unglamorous legal drudge work. But in many Latin American countries, a notario is an ill-defined but powerful figure with broad legal authority, often someone with the connections needed to navigate bureaucracies that, while arcane, are also flexible. Unscrupulous notarios in the U.S. exploit these facts to con immigrants into believing that all it takes to finally get legal is the right person to file the paperwork.

Both shady notarios and their victims are usually immigrants. In going about these transactions, immigrants are much more likely to trust their own people. They speak the language, they have connections in the home country, and they understand the endless daily anxieties of undocumented life.

Most notarios operate under the radar, but others, like Cabrera, do the opposite: They build trusted public reputations as community leaders and advocates.

In lengthy interviews with BuzzFeed News, conducted in Spanish, Cabrera denied breaking any laws. He insisted, in spite of ample evidence to the contrary, that he never charges for his services, and that every cent he ever received was a voluntary donation. And he defended his track record as an activist, saying that he contributed to every major immigrant rights victory in recent memory, from driver's licenses for the undocumented in California to Obama's deferred action programs.

"My conscience," Cabrera said, "is clear."

Cabrera’s offices are divided into three cramped rooms along the same dark hallway. The reception room is decorated with poster-size, framed collages of newspaper clippings. Sometimes copies of the same article show up twice.

On the morning of his first interview with BuzzFeed News, Cabrera walked into the reception room and introduced himself. “Did you see the article in the New York Times?" he said. "I’ve had a very respectable trajectory.”

Wearing a gray suit with a shiny blue dress shirt, Cabrera sat down behind a cluttered desk, and, unprompted, unleashed a torrent of words. Cabrera speaks fast. He leaps wildly from subject to subject, often in the middle of a sentence. He asks himself questions, apropos of nothing, and answers them in the same breath. It’s enough to dizzy any listener.

“How could a barefoot indigenous boy achieve the highest dream of rescuing American democracy?” he asked. His upbringing, he said, had been the focus of a recent interview on the Spanish-language network Centroamérica TV. The answer begins with his birth “in a half-built adobe hut” in an indigenous village in Cañar, an Ecuadorian province nestled against the western edge of the Andes.

“When I was 5 years old, my mother sent me to school barefoot,” he said. “All the other children had shoes, and I didn’t. But I was too young to understand. Later, when I was 13, my mother told me, ‘The reason I sent you to school barefoot was so that one day, when you become an interesting man, a man who defends the civil and human rights of the people, you’ll remember the land where you come from, and that you come from humble origins.’”

In his quest to become such a man, Cabrera said, he obtained a doctorate in international law from the University of Guayaquil. (An official with the university was unable to locate a record of Cabrera’s degree.) Then he set off for the United States.

Cabrera entered the country, he said, “like any other indocumentado” — illegally, crossing the Mexican border into Arizona. He landed in Los Angeles, where he spent his first night sleeping in MacArthur Park. He moved to Lynwood, a majority-Mexican city in South L.A. County, where he had his first taste of activism gathering signatures to repeal a state law that barred undocumented immigrants from getting driver's licenses.

Cabrera made an impression in activist circles during those first years in L.A., said Elba Berruz, the longtime president of an organization of Ecuadorians in the United States. Berruz met him at a reception at the Ecuadorian consulate in Beverly Hills, where he introduced himself as a lawyer. "He was young and politically ambitious," she said. "Everyone would always ask, 'Have you met Oswaldo yet?'"

Above all, Cabrera had a way with reporters and camera crews. Berruz said he never got his hands dirty with community work (a characterization Cabrera disputes), but he would show up to meetings, where TV stations always wanted to interview him. “He was a smooth talker,” Berruz said. "Later I started to wonder whether he was paying them."

It was around this time, in 2004, that Cabrera took up the cause of Jonathan Martinez, an 8-year-old boy from El Salvador who was arrested by the Border Patrol as he tried to enter the country to reunite with his mother. Jonathan was released shortly after he was apprehended. This was routine: A settlement in a federal lawsuit from 1997 compelled immigration authorities to release unaccompanied minors in nearly all circumstances.

Still, Cabrera managed to spin Jonathan's release as an achievement of his group, the Coalición Latinoamericana Internacional. This turned into Cabrera's first highly successful media campaign, landing him an appearance with Jonathan on Sábado Gigante, a massively popular variety show on the Spanish-language network Univision. Sábado Gigante is the oldest and most beloved show on Univision, which has the largest primetime audience of any Spanish-language network, according to Nielsen. Cabrera was preaching his gospel to millions.

About two years later, an immigration judge allowed Jonathan to stay in the country. The boy had actual lawyers — pro bono attorneys from the Catholic Legal Immigration Network. But to this day, Cabrera takes credit for the victory, calling it "his first case."

This is the story Cabrera tells about Jonathan: After a short time in the United States, the boy learned to speak decent English. Sensing an opportunity to "humanize" the judge in his immigration case, Cabrera coached Jonathan to sing the American national anthem during his court hearing. The judge, impressed and properly humanized, allowed Jonathan to stay.

The earliest public accusations of fraud appeared in the newspaper El Diario de Hoy in 2006, the same year that Jonathan won his case. The paper reported that two Salvadoran families in L.A. claimed Cabrera had swindled them out of thousands of dollars by promising to get their kids out of immigration custody.

Today, Cabrera claims these families were manipulated into lying by the editor of the newspaper, who had a personal vendetta against him. Either way, the stories were buried in the avalanche of good publicity that followed Jonathan’s case.

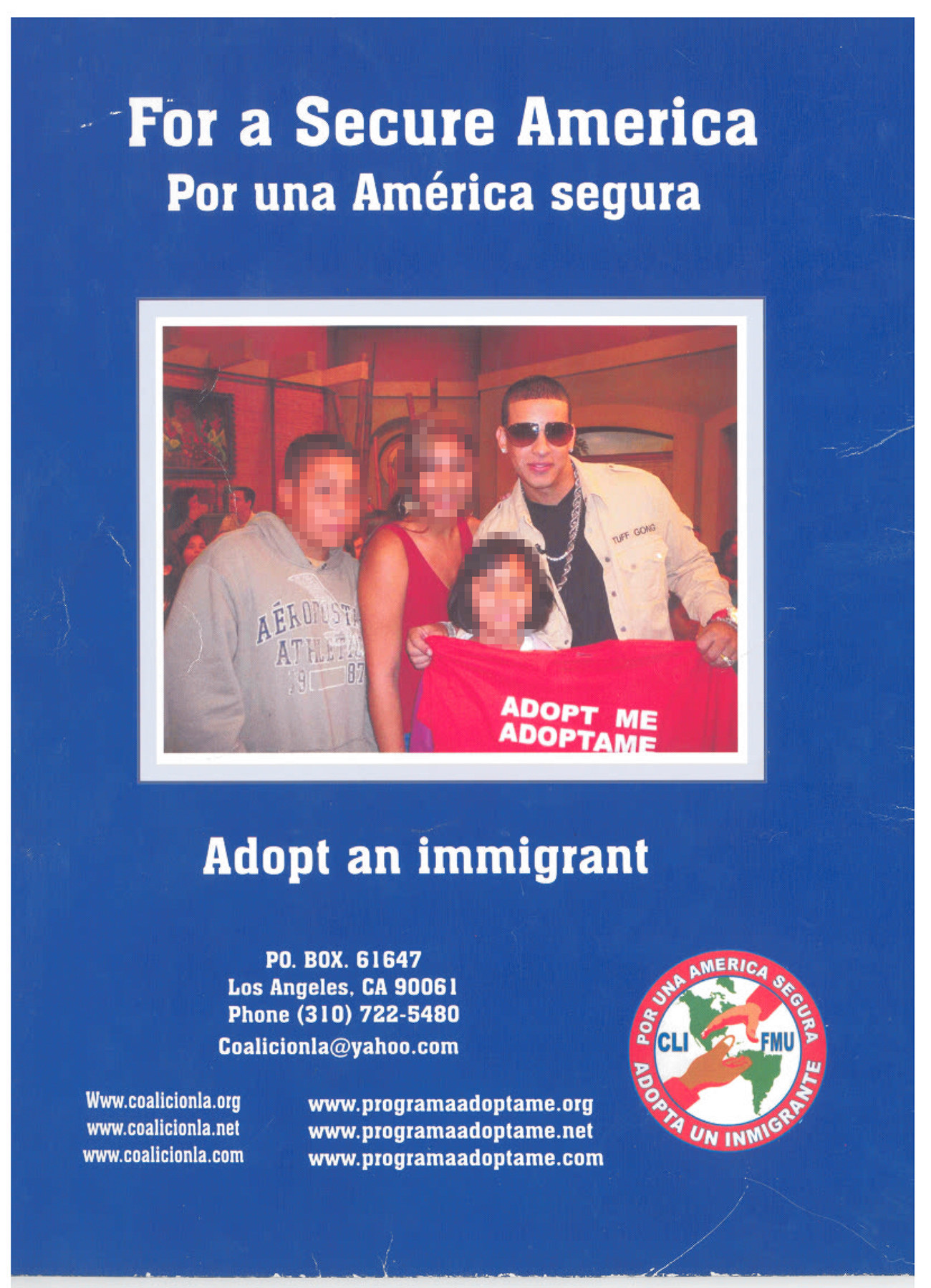

From that point on, Cabrera adopted defending the rights of immigrant kids as his cause. In 2007, he came up with his flagship campaign, "Adopt an Immigrant," in which U.S.-born children "symbolically adopt" their undocumented parents in order to keep them from getting deported. Cabrera claims that this strategy — by "humanizing" judges, as with Jonathan's case — has prevented thousands of families from being torn apart by deportations.

Because Cabrera has never represented anyone in court, it's impossible to know whether this tactic has actually worked in any specific immigration proceedings. But as a publicity stunt, Adopt an Immigrant was brilliant. Cabrera became a go-to source for stories about children left behind by deportations — or "orphaned by La Migra," as he would later put it in the title of a self-published book. For the first time, his appearances weren’t limited to the Spanish press. He was quoted twice in the Los Angeles Times, once on the front page, in stories about families split by deportations.

Adopt an Immigrant also led Cabrera to cross paths with politicians and pop stars, meetings that Cabrera brings up at every possible turn. In 2007, he flew to Miami for a taping of the Univision show Despierta América. Backstage, he posed for pictures with Daddy Yankee, the reggaeton superstar.

Cabrera recalls the meeting fondly. "I said to him, 'Daddy, I need a social change, but I can't do it by myself.'" Cabrera went on to use the singer's picture in promotional materials, and an article in New York's major Spanish daily, El Diario La Prensa, calls Daddy Yankee the "godfather" of Adopt an Immigrant. (Daddy Yankee's publicist acknowledged the meeting in an email to BuzzFeed News, but denied that he ever endorsed Cabrera's campaign.)

Then there was the meeting with Hillary Clinton, which took place, according to Cabrera, at a private fundraiser in Lynwood during the presidential primary campaign in 2007. The meeting was reported by the Spanish newswire EFE at the time, but it's not clear whether Cabrera was the sole source for the information. Clinton's office did not respond to a request for comment. But in Cabrera's telling, Clinton enthusiastically endorsed Adopt an Immigrant.

"It was very important for me," Cabrera said, "when Mrs. Hillary Clinton applauded, and said to me, 'You are very intelligent. Where are you from?' And I told her, 'I'm just an Indian from Ecuador.'"

In 2009, Berruz, the Ecuadorian community leader in L.A., stopped seeing Cabrera around. "He just sort of disappeared," she said. “People had started speaking poorly about him. ... It was already known that he was charging large sums of money to help people with immigration."

One day, Berruz saw Cabrera on television, this time on a show that taped in New York City. Cabrera had settled in Corona, Queens, an immigrant enclave with a large Ecuadorian population. Every block of the neighborhood's main drag, Roosevelt Avenue, is a dense mosaic of storefronts offering services to immigrants, among them countless lawyers and notarios.

Cabrera set up shop in a borrowed corner of a store on Roosevelt Avenue and went about gathering new clients for his business. One of them was Luis Enrique Flores — the immigrant from Cabrera’s same small province in Ecuador who says he dined with Cabrera shortly after he announced his hunger strike.

When Flores landed in immigration custody, friends of his hired Cabrera after seeing him on television. At the same time, Flores hired an attorney in Texas, where he was detained. With the lawyer's help, Flores was released and returned to New York.

Flores continued paying Cabrera to help ensure that his case would be permanently resolved. Over the course of several months, Flores said, he paid Cabrera more than $30,000. He trusted Cabrera for many reasons, among them the fact that they came from the same place and had become friends. "How was I going to think that he was running a scam?" Flores said to BuzzFeed News from Ecuador, where he returned a few years ago.

Flores said that he asked around in Queens about Cabrera, and found several other people who said they had given him money. "Just like he scammed me, he scammed many others," Flores said.

Cabrera denied that he took Flores’ money without helping in his immigration case. He said he accepted donations from Flores (though less than Flores says he paid), and that Flores’ release from detention and his ability to remain in the country were the result of his work.

Meanwhile, Cabrera ramped up his activist campaigns. He promoted his self-published book, whose title translates to American Children Orphaned by La Migra. He announced his hunger strike from the church in East Harlem.

But Cabrera also raised eyebrows in activist circles. Vicente Mayorga, an Ecuadorian community organizer with Make The Road New York, recalled going with Cabrera to a forum in Connecticut on immigration reform. After the meeting, Cabrera announced that anyone needing additional help should come see him in private.

Mayorga, who had heard about Cabrera’s side business, confronted him. "I told him that you don't charge people for this," Mayorga said. "You don't charge a cent."

Cabrera complained that Mayorga was interfering with his work. "What work?" Mayorga replied. "This isn't work. Pick up a shovel. That's work."

Cabrera left New York some time in 2011 and stayed relatively quiet for a couple of years. He resurfaced again in Los Angeles in 2013, opening the offices he now occupies.

This time, Cabrera invested in some infrastructure and built up his staff. He went to Miss El Salvador USA, a local beauty pageant, and recruited 22-year-old Vanessa Carolina Guardado to work as a spokesperson for the Coalición. He produced ads for the internet in which Guardado sits cross-legged at a desk, flatly reading the requirements needed to qualify for deferred action.

Daniel Sharp, legal director of the Central American Resource Center (CARECEN), first noticed Cabrera's operation around this time. He had seen Cabrera's ads in the local Spanish papers, and even though Cabrera never used the word "notario," the ads struck Sharp as no different from those of other people who illegally peddled immigration services.

Sharp realized that Cabrera was up to something different when he got a call from a family who, thinking they had the address for CARECEN, had instead gone to see Cabrera. Sharp googled the name of his own group and saw, at the top of the search results, a paid advertisement for the Coalición Latinoamericana Internacional. He tried a few different searches, and found that the same ad came up under queries for NALEO, the National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials.

Sharp quickly found Cabrera’s media appearances. “It was all a front — a cover to get people in the door of his business,” Sharp said. “It went from an interesting ad in the newspaper to our top priority. This guy was using us to rip people off.” That family’s case became the first lawsuit that Sharp filed against Cabrera.

Another one of Sharp's clients is a woman named María. (Because she is undocumented and fears deportation, María asked that BuzzFeed News withhold her last name.) When María, who comes from El Salvador, asked around for someone who could help her obtain citizenship for her husband's parents, a friend referred them to NALEO — but gave them the address to Cabrera's office.

The first day that María and her family showed up at the Coalición, Cabrera said he could easily get citizenship for the parents. Then he asked about María. She told him she was undocumented, but that her husband was a legal permanent resident. No problem, he said. I can get you your papers.

Cabrera told María that there was a new law that would allow her husband to petition for her to obtain legal status. There was no such law. María's husband had, in fact, already petitioned on her behalf years before. However, since she was already in the country illegally, she would have had to go back to El Salvador, risking the very real possibility that she would get stuck there if her petition was denied.

Cabrera insisted that the new law meant she could go through with the petition from inside the U.S. "I asked him when this new law came out, because I watch the news, and I hadn't seen anything about it," María said. "He told me that not all the news comes out on television, that some of it only comes out on the internet. And I don't have the internet." (Cabrera denied telling María about a fictitious new law, and denied charging her any money, suggesting that receipts she provided to her lawyers were forged.)

Cabrera was convincing. He spoke fast and he spoke well. Cabrera had seen María looking at the framed newspaper clippings on the wall of his reception room, and told her they were all cases he had won — citizenship, green cards, work permits. "He said he would help us, that he could solve any problem we had," María said. "I believed him. His words were sweet. They were like the words of a lawyer who knows about the law. And I didn't know anything. That's how he made me feel."

More than anything, María felt tremendous relief at the thought that she could get papers, a work permit, a job doing something other than occasional sewing for people in her church group. "Being here without papers, living off my husband, without being able to get a good job — it doesn't make much sense to me," she said.

Cabrera scheduled meeting after meeting with María, telling her that he was filing all the necessary papers and that her case was progressing. On a few occasions, she brought her youngest son to his office. The child, who was born in the U.S., is autistic and hyperactive. Cabrera was impatient and unkind with him, María said, once forcing him to wait alone in the hallway after he spilled some soda on his carpet.

Cabrera charged María after every meeting. She made sure to ask for receipts, which bore the logo of the Coalición Latinoamericana Internacional. Cabrera charged her, in total, $5,700.

In preparation for his second interview with BuzzFeed News, Cabrera removed the framed newspaper clippings from his reception area and hung them on the walls of the conference room next door, flanking a large American flag that was pinned to the wall. He summoned two former clients for the occasion, both women in their seventies who had obtained citizenship through the Coalición.

One of them, Margarita Chipres, wore head-to-toe camouflage — a ritual of support for a grandson in the army. "Thank God I'm a citizen now," she said.

"Thank God," Cabrera repeated, sitting at the head of the conference table. "Without God we are nothing."

"Thank God, and thanks to him," Chipres said, gesturing toward Cabrera.

Chipres and the other client had been legal permanent residents for decades, and qualified to take the citizenship exam in Spanish. Whereas an immigration lawyer would have charged them thousands of dollars, they said, Cabrera did the work for free — except for a voluntary donation. Asked how much they donated, both women said the same thing: $400.

Throughout his interviews with BuzzFeed News, Cabrera strenuously denied every allegation against him, calling them "calumnies." He insisted that he does not and has never charged people to help with their immigration cases. "People contribute voluntarily," he said. "And if they can't contribute, that's fine."

In the answer his lawyer filed in the first lawsuit against him, Cabrera acknowledged that he "contracted" with the plaintiffs for $2,500 to provide "immigration consulting services." When that was pointed out to him, Cabrera told BuzzFeed News this was a mistake. "I'll have to talk to my lawyer."

In February, the day after he was served with the second and most recent lawsuit, Cabrera purchased a surety bond — one of many requirements to practice as an immigration consultant in California. He acknowledged that he didn't have the bond before this year, but brought it up repeatedly to say that what he does is legal. Although it mentions the Coalición, the bond is not under Cabrera's name.

Cabrera and his organization also are not accredited as immigration consultants by the federal government, nor is the Coalición registered as a nonprofit.

According to state records, the Coalición did briefly register as a nonprofit in California in 2007 — the same year Cabrera started Adopt an Immigrant — but its status was suspended by the state tax board. When asked why the group's nonprofit status appears as suspended on the state's website, Cabrera said that the original incorporation was filed, and then allowed to be suspended, by some unknown person in an attempt to besmirch the reputation of the Coalición. "It was what you might call a dirty trick," he said.

So, Cabrera said, are the lawsuits against him, which he explains by saying that CARECEN sees him as a threat. "Their offices are empty every day, because they lack the warmth of popular support," Cabrera said.

Cabrera at one point suggested that CARECEN was involved in a plot to "disappear" him. "They want me gone," he said. He resisted giving details, but recalled a time when, in New York, during his hunger strike, he was visited by three very tall men in suits, whom he presumed to be federal intelligence agents. He also recalled how more recently, in Los Angeles, the tires of his car suspiciously burst.

"The world is full of bad faith and bad intentions," Cabrera said. "They think I'm destroying their business. What business? For them, these people are a product. Not for me."

Este hombre dice que lucha por los inmigrantes, pero ellos dicen que los estafa

buzzfeed.com

This article has also been translated into Spanish