In 1980, Jon Rangi was found by Brisbane Children’s Court to be “uncontrollable”.

Already, the 11-year-old had lived a tough life, growing up in grinding poverty with four siblings and an abusive, alcoholic father who terrorised the family, beating and raping Rangi’s mother in view of the children.

She left the relationship, taking the kids with her, but things were barely any better: They were kept on the move across NSW and Queensland as Rangi’s father took pursuit, forcing the family to change names several times.

Rangi’s mother eventually met another man and he moved in with the family in Queensland, though, for the children at least, there was no respite from abuse.

“My stepfather used to lock me under the house,” said Rangi, “because he knew I was scared of spiders."

While he was locked up, often for several hours at a time, his stepfather abused his sisters, he said.

So it’s no surprise that as a boy, Rangi would regularly run away from home, spending stretches of time sleeping on the relative safety of the streets. But those spells of safety would always be broken by police picking him up and returning him to his stepfather.

And so, after multiple attempts to run away, Rangi said, the court listed him on an “uncontrollable order”. The charge was common at the time. It criminalised children for being abused, placing them in the care of the state.

As Forgotten Australians, a landmark report stemming from a 2003-4 Senate inquiry into children in institutional and out-of-home care, found: “These were not crimes of the child. They were crimes of the parents or, in a sense, crimes of a society that at the time was not providing anywhere near sufficient help and assistance.”

Rangi became the responsibility of the state of Queensland and was deposited in Wilson Youth Hospital, a place now notorious for physical abuse, solitary confinement, and using experimental sedatives to control young people.

Rangi said each night a warden – one who had initially showed kindness to him – would creep in and molest Rangi and the boy next to him.

“There was one who came around who’d give us cigs, coffee, that was the beginning of it,” said Rangi. “Then touching us in sexual ways, threatening us if we said anything, did anything, he’d take us to the dungeon [Wilson’s basement laundry] ... put us in there and kill us.”

Guilt and shame, more than fear, compelled Rangi to keep the abuse to himself for most of his adult life. He only recently told his family of his ordeal.

As a boy, however, he was questioned several times by staff who’d somehow figured out what was happening. “They told us we were safe and they were going to protect us,” he said. The police were never called.

As terrible as it was, Wilson Youth Hospital was in no way exceptional. For most of the last century, an astonishing number passed through institutions that, ostensibly set up to protect children and young people, instead brutalised, abused, and neglected them.

Forgotten Australians, the 2004 Senate report, found upwards of 500,000 children were housed in institutions or foster care in the last century: “Emotional, physical and sexual abuse, and often criminal physical and sexual assault … humiliation and deprivation of food, education and healthcare … was widespread across institutions.”

Five years later, 900 “care leavers”, as they’re known, packed parliament’s Great Hall to hear then prime minister Kevin Rudd apologise for this “ugly chapter in our nation’s history”.

“We look back with shame that many of these little ones who were entrusted to institutions and foster homes instead were abused physically, humiliated cruelly, violated sexually,” he told the crowd. "And we look back with shame at how those with power were allowed to abuse those who had none."

But Rangi, despite being placed into the care of the government as a child, is not a citizen. Like more than half a dozen forgotten Australians who were either made wards of the state or placed in state care who BuzzFeed News has spoken to, he is now being deported due to his criminal history.

Overwhelmingly, drug crimes constitute the bulk of their long criminal records. It’s not surprising – the Senate report found a direct link between time spent in state care and substance abuse.

“Resorting to drugs, both licit and illicit, was a common practice to obliterate the past present pain and suffering,” it found.

By age 13, Rangi’s life was an endless cycle of running away to the streets and sleeping rough to avoid the cops, only to be caught and thrown back into the places he was escaping. All up, he was returned at least four times to Wilson Youth Hospital. Not once did the police ask why he was running.

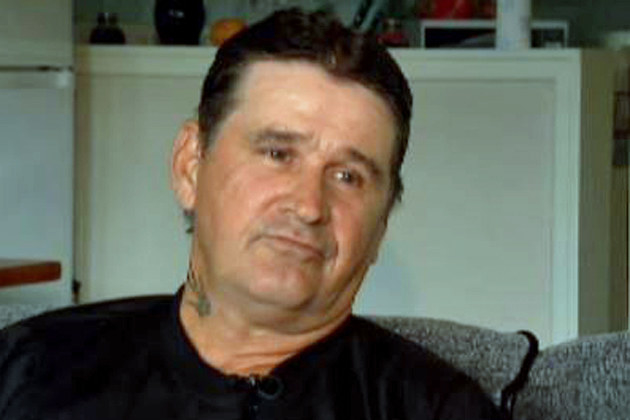

“I’d had enough of life. It was too hard,” said Rangi, speaking from from Western Australia’s Yongah Hill detention centre.

“With the molestations that went on [in Wilson Youth Hospital], I thought I was a bit of a freak. I just had enough and that’s when I managed to get a hold of sleeping pills. Popped the whole packet and swallowed a whole bottle of rum after that.”

Around the same time, in South Australia, 14-year-old Gerrard McLaughlin was running away from the welfare system too. Since his parents had split up a couple of years earlier, his mum had been working more and more, leaving McLaughlin and his siblings to their own devices.

Born in Ireland, the teenager was now in Adelaide, skipping school, smoking weed, and getting in trouble with the police. Then the government welfare worker began visiting.

“She said that I was angry and abusive and my mum couldn’t handle me, I needed structure, a father figure, and all this other crap,” McLaughlin told BuzzFeed News.

The social worker told McLaughlin’s family he might be better off being placed in a foster home, suggesting with kindness it was the best thing for the wayward teenager.

McLaughlin was simply told his family didn’t want him.

“The whole time I thought my family didn’t want me home, but she was telling them this was the best thing for me,” said McLaughlin.

In testimony after testimony, the Senate inquiry heard the same story: children told that their family didn’t want them and removed into care.

Even on the day of his brother’s funeral, McLaughlin was kept from grieving with his family.

“I didn’t understand what was going on,” said McLaughlin. "I was told Mum didn’t want me at home anywhere."

He was desperate to go home, but knew that if he did, the cops would just pick him up and return him to foster homes. So, like Rangi, he chose to sleep on the streets.

When he was eventually picked up – he was always eventually picked up – he’d be taken to a youth remand centre as the government tried to find him another foster family.

It was around this time he started getting a serious criminal record. There were break-and-enters and stealing cars (“actually a lot of stealing cars”).

McLaughlin entered the welfare system as a truant, and graduated a drug addict.

Despite now being close to his family, the pain of rejection felt as a child still cripples McLaughlin. He can’t talk about this period in his life without breaking down.

With the help of a drug counsellor and psychologist, he’s started working through his issues: his life of addiction and crime, and the dark secret of sexual abuse that he kept to himself for most of his life.

McLaughlin has only told a handful of people exactly what happened.

A psychologist, in evidence tended to court for a driving offence, described “a pattern of neglect and traumatic abuse” that has led to “fragile self-esteem, drug abuse and poor decision making”, as well as PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

Later this year, McLaughlin will tell the royal commission into institutional responses to child abuse exactly what happened when he was a ward of the state.

“The way I look at it in my mind, I have to work up to be able to say it once,” McLaughlin said through tears.

Of the 889 submissions from “care leavers” received by the 2004 Senate inquiry alleging abuse, 21% were sexual and 35% were physical.

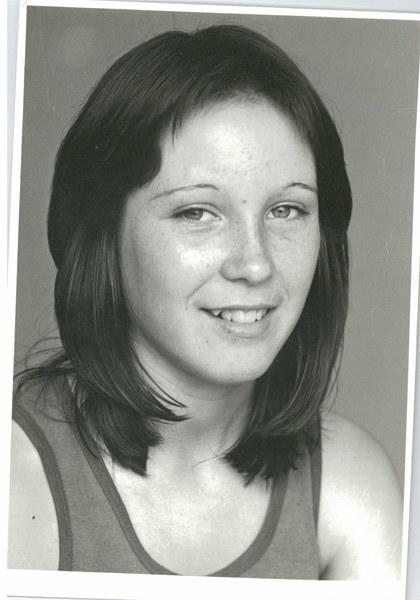

Michelle Whitehouse, a 55-year-old grandmother who BuzzFeed News reported on last year, is also planning to give evidence to the royal commission about sexual abuse she suffered at Victoria’s Sutherland Homes where she lived for seven years from age 4.

Whitehouse, who has been in immigration detention for 15 months awaiting deportation to the UK for a 12-month marijuana conviction, had always told people she couldn’t remember anything of those years spent institutionalised. Whitehouse’s daughter Rhiannon told BuzzFeed News last year: “She doesn’t talk about that place much. I don’t know if she really doesn’t remember but I do hear her talk about some things ... She just says it was a horrible place.”

Now, having seen the royal commission in full swing, Whitehouse has decided that with a counsellor’s help she’ll talk about the abuse she’s hidden her entire life.

Allegations of abuse at Sutherland have been made by others. Berry Street, as the organisation that ran the Sutherland homes is now known, apologised in 2006 for “physical, psychological, sexual or social harm” that may have occurred to children in its care, and Melbourne lawyer Angela Sdiris is currently pursuing claims on behalf of several former residents for sexual abuse they suffered while Whitehouse was a resident.

As well as hearing from individual witnesses like Whitehouse and McLaughlin, the royal commission has been probing individual institutions.

It recently reported on Turana, a government-run institution that closed in 1993, hearing from four witnesses who alleged sexual abuse. Its former superintendent admitted knowing sexual abuse was occurring but doing nothing to prevent it; another staff member employed at the centre said boys were too scared to report abuse. One witness told the royal commission that when he reported sexual abuse by another resident, staff concluded he was homosexual, and subjected him to 12 rounds of electric-shock aversion therapy.

Raymond Pedrana was a resident at Turana for a couple of years around 1977. He recalls it as a brutal place and the first boys home he was severely beaten in.

“It hardened me up a bit,” he told BuzzFeed News.

His stay in Turana led to a lifetime in institutions, from state homes as a child to jail, then immigration detention.

Like McLaughlin and Whitehouse, his troubles began when his parents split up. Initially living with his father in Melbourne, Pedrana got in trouble for trying to steal money, which he says was to get back to his family in Sydney.

His father relinquished custody of him when he was 9, landing him in Turana until he ended up in his mother’s care when he was 10. Home life was hardly any more stable, however, as his mother struggled with alcoholism and a run of bad luck.

“Mum was a drinker, but wasn’t a bad drinker,” said Pedrana. "She had a couple of strokes and a bad run and welfare started coming."

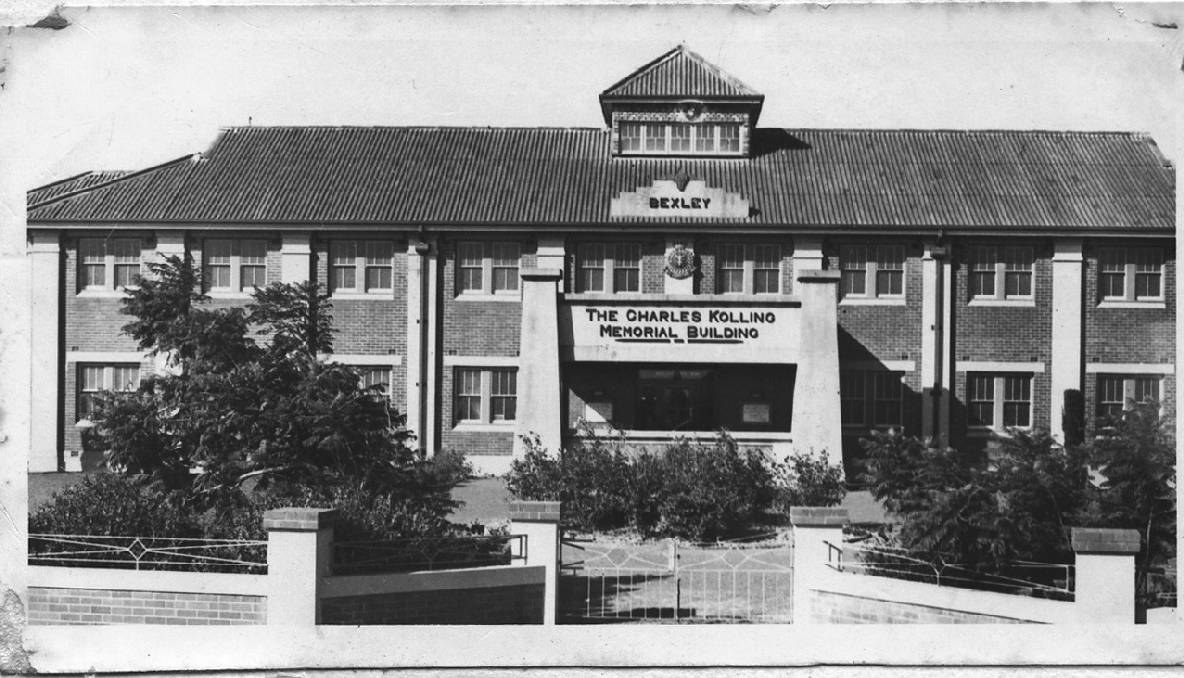

He was placed in the Salvation Army’s Bexley home, another institution recently examined by the royal commission.

“At Bexley, an officer came in one night and wanted to come and have sex,” said Pedrana.

Though he was only 12 at the time, Pedrana claims he warded off the advance with a threat of violence. The royal commission found that from the time it was established to the time it shut its doors, sexual abuse and “brutal” physical abuse was widespread at Bexley, and the Salvation Army has paid out at least five ex-gratia payments for sexual abuse.

Earlier this month, two former superintendents were charged for offences committed between 1968 and 1974, just three years before Pedrana says he first came to Bexley.

While passing between the care of his mother and social welfare institutions, Pedrana began getting in trouble, racking up convictions for stealing and break-and-enters. He was eventually placed at Sydney’s Daruk Training School.

“I met all the future crims [sic] there,” said Pedrana. “We became friends and they were the only people I knew from boys homes.”

It was, even by the brutal standards of the time, a tough place, prompting a recent apology to some former residents from the state government.

It’s by no means inevitable that having entered institutions as truants and runaways, young men and women would end up incarcerated.

But that pattern is extremely common. “Many [care leavers] turned to illegal practices such as prostitution, or more serious law-breaking offences, which have resulted in a large percentage of the prison population being care leavers,” reported the Senate inquiry.

More recent work carried out by the University of NSW – which surveyed and interviewed 700 people in care between 1939 and 1990 – found that 27% of males had a history of incarceration, and 20% a history of conviction.

For Pedrana, the cycle of imprisonment started early. At 14 and 9 months, he was deemed by a court “unsuitable for a child welfare institution” and placed in Emu Plains Correctional facility – an adult jail.

“They had us separated from the mainstream … locked in the cells,” said Pedrana.

Apart from meeting adult criminals, jail was where the teenager first tried heroin. “It was easier to get [inside] than on the streets,” said Pedrana, “Once I started using drugs that ruined my life.”

After three months he was released and sent to the notorious Mt Penang Boys home and then Endeavour House. “That was the worst place for physical abuse,” said Pedrana. "First day I get there I got the shit kicked out of me badly and that happened more or less daily."

Endeavour House, set up for absconders and boys with more serious criminal records, has a well-documented history of violence. In 2011, the ABC reported 35 violent deaths were linked to former residents, and its alumni include some of Australia's worst killers. Boys were kept in isolation, deprived of food, and subjected to the constant threat of violence.

“I witnessed a really bad assault – a bloke got picked up and thrown into a concrete wall,” said Padrana. "I was warned [by guards] if I said anything about it I’d get twice as worse as he got."

By the time he was 18, Pedrana had racked up five convictions for stealing cars, another eight stealing charges, and five driving convictions.

“I was raised in boys homes and didn’t know what being normal really was,” he told the Immigration Department. “I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me about the way I raised myself but believe me when I say I am sorry when I hurt people by stealing.”

Now, as an adult, he has a lengthy criminal history that includes 18 driving related convictions, such as driving while disqualified, plus scores of drug convictions, some apprehended violence orders, and armed robbery. Of his 57 years, he's spent just five outside jail, though he still racked up minor convictions during that time.

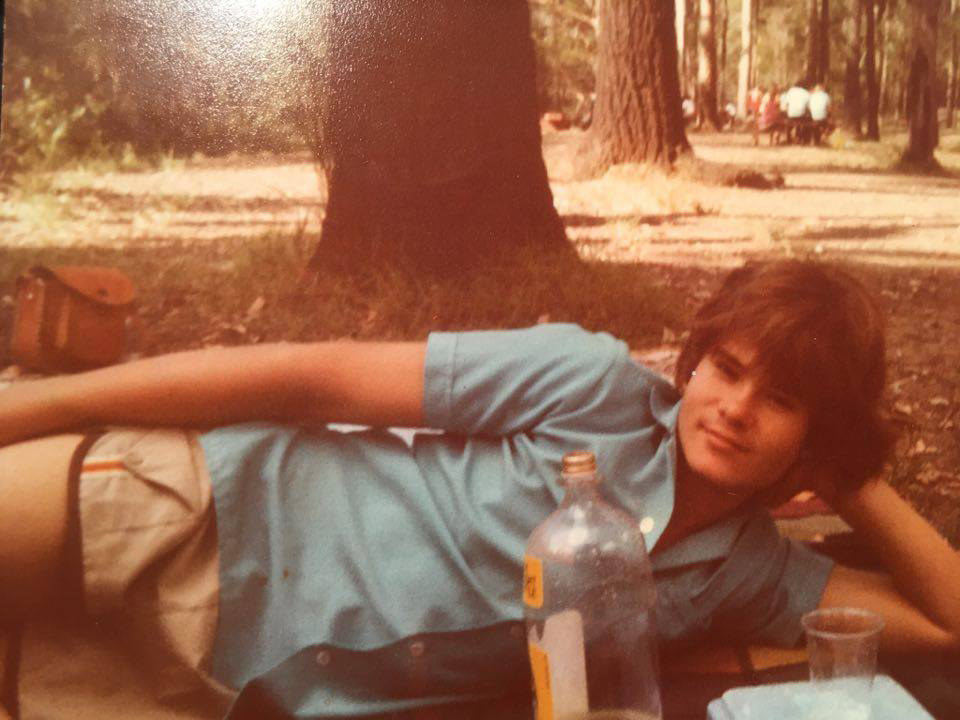

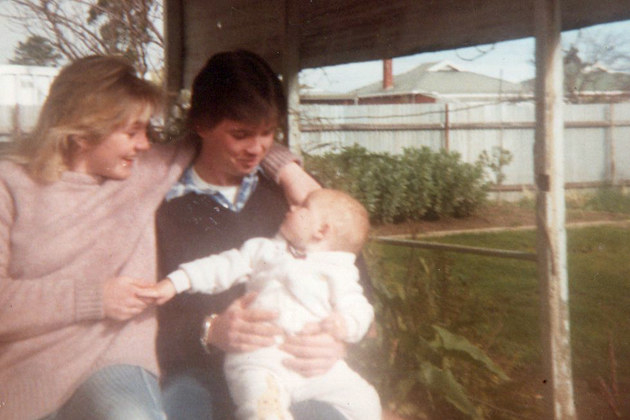

Jon Rangi’s path as a juvenile closely followed Pedrana’s: stealing, breaking and entering, drugs. But when, at the age of 15, he had his first child, things changed.

“I promised myself that if I was ever to have kids that I would, no matter what, I’d be there with them to make sure no abuse ever happened to them and no men would ever, ever hurt them or touch them in any way,” said Rangi.

And for 18 years, he stuck to that pledge. According to him, he found God and fathered another three kids. In 2000, his wife and two eldest children were naturalised as Australian citizens.

But in 2006, life fell apart. While working as a security guard on the Gold Coast, he broke up a violent brawl instigated by bikies. He was knocked out cold by a bottle smashed to his head.

“The actual brawl went on for 13 minutes,” said Rangi. "A lot of patrons jumping in and getting bashed, women getting bashed."

The brawl was traumatic, and set him on a path back towards drug abuse. He was diagnosed with PTSD and put on WorkCover for two years, and things started spiralling out of control.

“I started going to the clubs, started drinking, then the drinking turned to the party drugs,” said Rangi. “The party drugs, the only reason I got into them was because I felt normal again, I felt alive again.”

His marriage was disintegrating, and Rangi was becoming dependent on drugs, falsifying prescriptions to and breaking into chemists to obtain pseudoephedrine and sell it in exchange for drugs. Eventually, he says, he worked out he could start making the drugs for himself.

Rangi was never a dealer; the sentencing judge recognised that he was manufacturing meth for his personal use and noted the sad circumstances of his downward spiral. “The facts speak to the sad deterioration of a man who had been a productive member of the community," the judge said. "You were a family man. You raised four children. You had held the responsible position of a security officer."

“You turned to methylamphetamine to help you deal with the trauma of that experience [the brawl] and developed a raging drug habit that ultimately destroyed your marriage and led to you being here.”

Gerrard McLaughlin graduated from petty crime to stealing cars.

Similarly, Michelle Whitehouse has a long history of drug offences, mostly for lower-level marijuana offences, though has spent two stints in prison, one for trafficking.

They all share strong ties to Australia, having come to the country at a young age.

But under Australia’s immigration laws, any non-citizen who is convicted to 12 months or more is automatically stripped of their visas, regardless of the circumstances. They are sent to immigration detention where, in most cases, they spend several months or more fighting to have the decision revoked.

According to figures from the Immigration Department, 1,526 people have been deported since the tougher law came into effect in 2014. All were stripped of their visas after serving custodial sentences and taken into immigration detention.

Michelle Whitehouse, who came to Australia when she was 2, has a long line of Australian family on her mother’s side that she says dates back to 1840. As well as her mother, her children and grandchildren, who are also of Indigenous descent, are Australian citizens.

Raymond Pedrana came to Australia at age 4 and has two Australian-born children and an Australian-born father. He's now living in New Zealand, hoping to get the chance to come back to Australia and be with his family.

Jon Rangi’s family in Australia includes his wife and five adult children and grandchildren, who are all citizens of the country.

Gerrard McLaughlin, who came to Australia aged 4, is much luckier than the others: after spending six months in immigration detention, the minister revoked his visa cancellation. His cause was assisted by South Australian senator Nick Xenophon, who lobbied the immigration minister to give McLaughlin a second chance.

“He was under our protection and we stuffed up,” Xenophon told BuzzFeed News.

“I would back the same view for anyone in a similar situation. We spent a lot of time on this, we did a lot of work and we pushed really hard. And the minister showed compassion and made the right decision.”

Although McLaughlin is now a free man in Australia, the entire process has damaged him.

“I’ve been in jail before and getting out you're excited and happy. This time I’m still angry. I’m confused I suppose,” McLaughlin told BuzzFeed News. “At this stage in my life when I was trying to get everything together it was really beyond me and really damaging. It’s set me back quite a bit.”

Seven years ago, then opposition leader Malcolm Turnbull broke down as he delivered his own apology to forgotten Australians.

“We are sorry because none of us can give back what was taken,” he said. "We are sorry because not one of us here today has the power to undo the damage done."

Earlier this month, his government announced a national redress scheme for child sex abuse survivors. It will provide payments of up to $150,000 per survivor, at a cost to taxpayers of $550-750 million.

Whitehouse and Rangi, who remain in immigration detention, may well be eligible for those payments. So too might McLaughlin. Pedrana will probably never be compensated for the violence he suffered in state care.

A spokesperson for immigration minister Peter Dutton released a statement to BuzzFeed News in response to questions about the cases of the Forgotten Australians.

“Decisions to revoke a visa cancellation are not taken lightly, and involve consideration of a range of factors, including information provided by the non-citizen under natural justice provisions,” it said.

Either way, despite a government apology and offers of redress, the “care leavers” alone will be forced to carry the burden of government policies that removed them from their families and placed them into institutions, and a society comfortable with looking the other way.

“We must also be unstinting in our profound sympathy, compassion, respect, and understanding for those for whom the scars inflicted by years of trauma may never heal,” Turnbull told the Great Hall nearly seven years ago.

In October, when a solicitor for the immigration minister provided reasons for rejecting Rangi’s appeal, he wrote: “The minister acknowledges Mr Rangi’s difficult childhood and alcohol and drug dependence has been the trigger for his criminal offending.” But, he continued, “the minister considers that this does not in any way excuse him”.