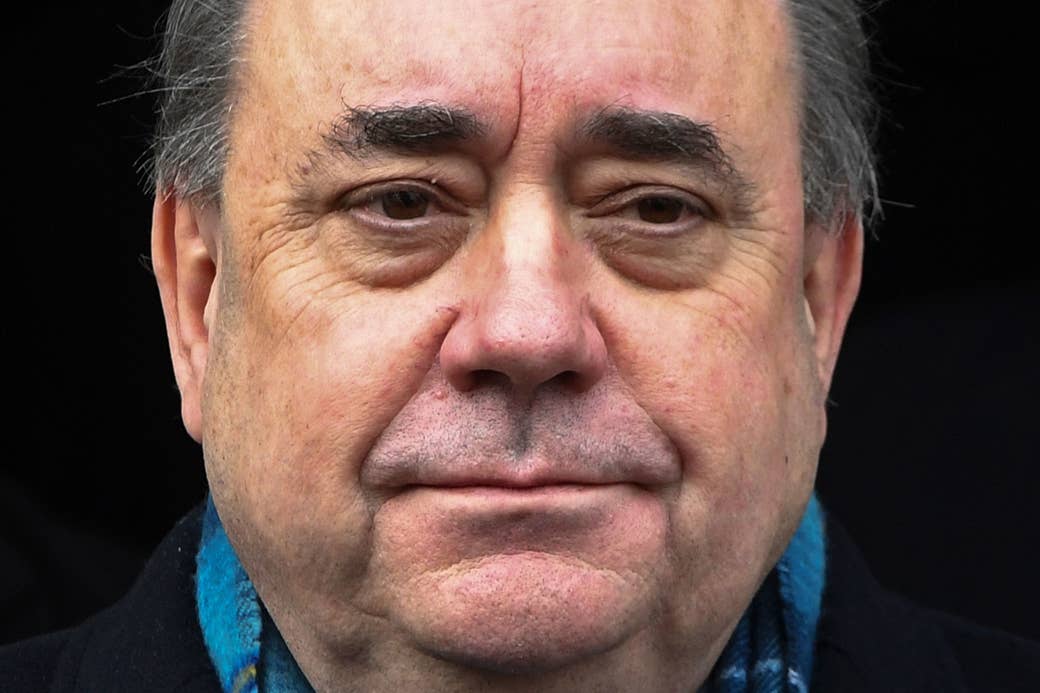

It’s difficult to convey to anyone living outside of Scotland the level of shock that gripped the nation when Alex Salmond was charged with 14 counts of sexual assault and attempted rape in January last year.

The former first minister and leader of the Scottish National Party, who brought the UK closer to the brink of separation than at any time in the past 300 years, is more than Scotland’s biggest and most enduring political beast.

He commands a paternalistic, almost regal presence north of the border, where he’s regarded by many as part national treasure, part rockstar and, for some, part god.

The 65-year-old walked free from the High Court in Edinburgh on Monday after being found not guilty on 12 of the 13 remaining charges — the 14th was dropped by the prosecution midway through the trial — and not proven on one charge of sexual assault with intent to rape. Not proven is a peculiarly Scottish verdict which means the jury didn’t feel there was enough evidence to justify a conviction.

Scotland had been bracing itself for its first significant #MeToo moment. Instead the nationalist movement has been plunged into a partisan row that threatens to tear it apart over why and how the trial ever went ahead, who was to blame and whether it was more about axe grinding and internal SNP score-settling than the pursuit of justice.

The case has led to an irreparable fall-out between Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon, his protégé, successor as first minister and formerly his closest ally. Senior party figures say there is now genuine animosity between the pair and zero chance of a reconciliation.

For most of the past 30 years the pair were politically inseparable as they guided the SNP from glorified pressure group to Scotland’s natural party of government.

Their successes were shared and jointly celebrated — the 1997 devolution referendum, the establishment of the Scottish parliament two years later, the first SNP-led administration in 2007 and, in 2014, their crowning glory, Scotland’s first independence referendum that fell agonisingly short of the 50% needed to take the nation out of the UK.

Since Salmond stood down as SNP leader shortly after the vote, anointing Sturgeon his successor, things have not gone well for a man grown used to being in the spotlight.

In 2017, he lost his Westminster seat to the Scottish Conservatives, leaving him without a constituency to represent for the first time since 1987.

Following a failed attempt to take over the Scotsman newspaper, he was reduced to fronting a small theatre show at the Edinburgh Fringe.

He later accepted a TV presenting job with Russia Today, a propaganda mouthpiece for Vladimir Putin whose other UK celebrity politician was George Galloway. Following a slew of criticism, including from within the SNP, Salmond pointedly said that if the BBC had offered him his own TV show he might have accepted.

The episode was significant for another reason; it was the first time Sturgeon publicly criticised her former boss, saying she would have “advised against it”.

Before any charges were brought against Salmond, the pair were already at loggerheads after she approved a Scottish government internal inquiry into allegations of sexual misconduct by him against staff.

The inquiry was botched from the start — a human resources officer spoke to two complainants before it had begun, tainting the process — and, after seeking and winning a judicial review, Salmond was awarded £512,250 to cover his legal costs

Sturgeon admitted meeting and talking to Salmond about the case five times, including at private meetings at her home, set up by her chief of staff, Liz Lloyd.

What appears to have wrecked their relationship beyond repair was a decision by Leslie Evans, permanent secretary of the Scottish government, to send the results of its internal inquiry to Police Scotland, triggering the criminal investigation.

Before the start of the trial, Salmond’s QC, Gordon Jackson, formerly a Labour MSP, suggested the government had ended up with “a great deal of egg on their faces”, while Salmond had been “publicly vindicated” by the judicial review.

Suggesting a political conspiracy, he told the court: “The Scottish government and people working in the Scottish government turned their attention very directly at the criminal process and with a clear motivation to influence that process in order to discredit the former first minister.”

At a pre-trial hearing, Jackson referred to a text sent by Evans which said: “We may have lost the battle, but we will win the war.”

Wondering aloud what war she might be referring to, he also pointed out that the Scottish government process had been so flawed, Police Scotland’s chief constable, Iain Livingstone, refused to use it as a starting point for the criminal investigation.

Jackson said a “concerted effort” had been made by people in government to influence the process and he referred to the “close involvement” of Sturgeon’s office although he did not “mean to suggest the FM has done anything wrong”.

However, the presiding judge, Lady Dorrian, dismissed this argument, ruling that using the judicial review as a form of defence would be “wholly irrelevant” during the trial and that the shortcomings of the government inquiry didn’t necessarily make the allegations against Salmond untrue.

Then there was the substance of the evidence against the former first minister which some observers felt was weak and insubstantial. Despite the high number of complaints from 10 different women, Salmond’s defence pointed out that police had interviewed more than 300 people in connection with the case.

One charge, alleging Salmond removed a woman’s shoe, stroked her foot and attempted to kiss it, was dropped. Others referred to him touching a woman’s knee over her clothing and asking a woman to re-enact a Christmas card scene of two people kissing under mistletoe.

In his defence Salmond insisted there was “nothing sexual” in his behaviour; that he and the complainants “were happy and egging each other on with banter and sexual innuendo” and that it was in the “nature of the office culture”. In response to some of the more serious allegations, the politician insisted the women concerned had consented.

Summing up at the close of the trial, Jackson said his client had not always behaved well and could have been “a better man on occasions” — but insisted he’d never sexually assaulted anyone.

Standing outside the court following his acquittal, Salmond referred to “certain evidence I would like to have seen led in this trial but for a variety of reasons we weren’t able to do so”.

He suggested he was holding back for now because the fight against coronavirus was far more important: “At some point that information, that fact and that evidence will see the light of day, but it won’t be this day, for a very good reason.”

It’s believed Salmond is determined to expose the alleged role played by individuals he feels acted as provocateurs, urging people who didn’t believe they’d been victims of crimes to contact the police.

He believes there was an effort to encourage women to “jump on the bandwagon”, to embellish and exaggerate details of incidents to bolster the criminal case against him.

There’s already speculation Salmond may now sue the Scottish government and, as part of his legal action, seek to obtain what he believes to be thousands of internal emails that he hopes will demonstrate a concerted campaign to discredit him.

A senior figure close to Sturgeon says there’s a fear Salmond is determined to restore his reputation even if it means bringing the independence movement crashing down around him and the serving first minister.

“I have spoken to a few people close to him in the last few weeks who said to me that they have encouraged him, on the basis that he was cleared, that he didn’t create carnage, but I just don’t know.

“With the coronavirus being what it is, [it’s hoped] he doesn’t do too much now but whether he does later, that’s obviously within his gift. We’ll just have to deal with that appropriately when it happens.”

The source denied reports today that Sturgeon has ever considered resigning as a result of the case, insisting that she was determined to remain in her job no matter what action Salmond takes.

Someone who worked alongside him at Holyrood for several years said he’d be considering what action to take from a personal point of view, rather than the impact it might have on the party or the nationalist movement.

The former first minister was, the colleague said, compulsively determined always to be proved right, punctuated with occasional bursts of explosive anger.

“He is a very complex character and a very difficult man to work with. Despite his public bravado, he has a deep-seated insecurity which amounts to a need to command and control everyone and everything around him.

“He had to win every conversation he took part in, even in private. He couldn’t just have an exchange of views, he had to own the conversation.”

Salmond was at his worst when he was in the company of people whom he perceived to be cleverer than him, according to the former colleague.

“You got a sense that he thought he had to work harder, and he could become nasty. He didn’t show any deference to long standing [officials] in the civil service.”

To journalists covering the political scene in Scotland, Salmond is a unique personality. Keenly aware of what made a ‘story’, he ingratiated himself among correspondents and editors, feeding them news lines, engaging excitedly in the process.

He has an unorthodox home life. Married to Moira, 17 years his senior, they were rarely if ever photographed together and they appeared to live separate lives; she at the family home in the north east of Scotland and he in London and latterly in Edinburgh, including at Bute House the official residence of the first minister.

To many outside observers his family was his job. and his professional and personal lives became increasingly interchangeable. It was an open secret among Scottish government and party staff that he had extra-marital affairs, but it was never discussed.

“He could be flirtatious with women,” said a colleague, “and, as someone working alongside him, you could never be entirely sure what their relationship entailed and whether, at some point over their shared 30-year history they may have had sex.

“There was a sense that you wouldn’t put it past him to be a bit of a shagger. There were instances when you thought it could get out and wreck the party.

“People were deferential to Alex. Everyone accepted that he was the leader and that he was better than everyone else.

“If you’re all conquering in your world, it’s easy to ...to confuse that people around you are there because they’re on your side. Some are, but there’s a much larger group of people pretending to be on your side, but who are just doing a job. Alex never understood that.”