One of Australia’s foremost forensic pathologists believes a fatal injury sustained by teenager Mark Haines, who was found dead on railway tracks in the 1980s, was not the result of a train. Haines’ family has long suspected he was murdered, however a coronial inquest into his death returning open findings.

It was 6:30 am on January 16, 1988, when a train driver departing the NSW regional city of Tamworth spotted in the distance what he thought were rags on the tracks.

It soon became clear that these were not rags, but a pair of legs. He pulled the emergency brake but there was not enough time to stop.

The train passed over the body of 17-year-old Gomeroi teenager Mark Haines.

Haines was lying on his back between the tracks. Despite the train moving over his body he sustained what were considered relatively minor injuries when compared with similar incidents.

Part of Haines’ skull – believed to be on his scalp – had been sheared off, possibly by the front of the train. No limbs had been amputated, but he had several deep cuts across his body probably caused by parts of the train hanging from the undercarriage.

Glenn Bryant, assistant station master at West Tamworth railway station, was one of the first to attend the scene. Bryant noticed a towel under Haines’ head and just one “50 cent sized” spot of blood, on a sleeper.

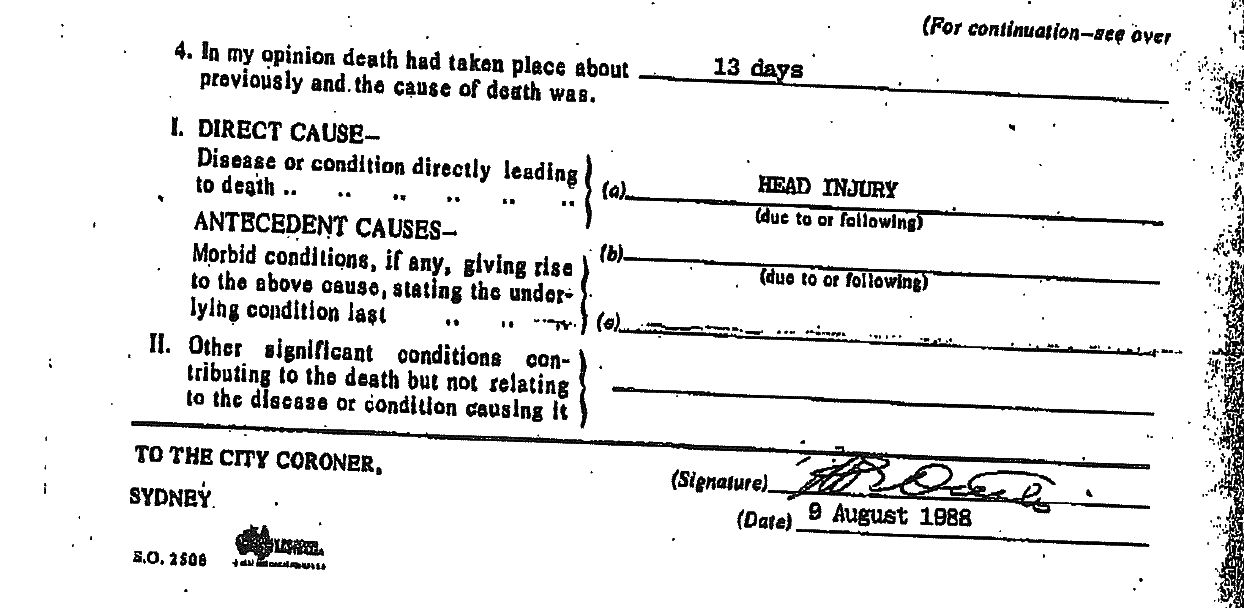

The first autopsy on Haines was conducted by a local GP. The family was not satisfied with the result and lobbied for a second autopsy, which was conducted 13 days after Haines died by the then NSW director of forensic medicine Dr Godfrey Oettle. It found that a head injury was the cause of death.

As part of BuzzFeed News’ ongoing investigation into Haines’ death, forensic pathologist Dr Johan Duflou agreed to examine Oettle’s findings and inquest testimony for signs of a possible homicide.

In Duflou’s clean white office, tucked underneath his house on Sydney’s northern beaches, the only clue to his line of work is a large and imposing black microscope on his desk.

He’s performed thousands of autopsies and appeared before thousands of coronial inquests.

The NSW Coroner’s Court routinely sets him the task of taking complex deaths, such as that of cricketer Phillip Hughes – who died in 2014 after being hit on the head by a cricket ball – and providing basic and clear medical explanations of what is likely to have occurred.

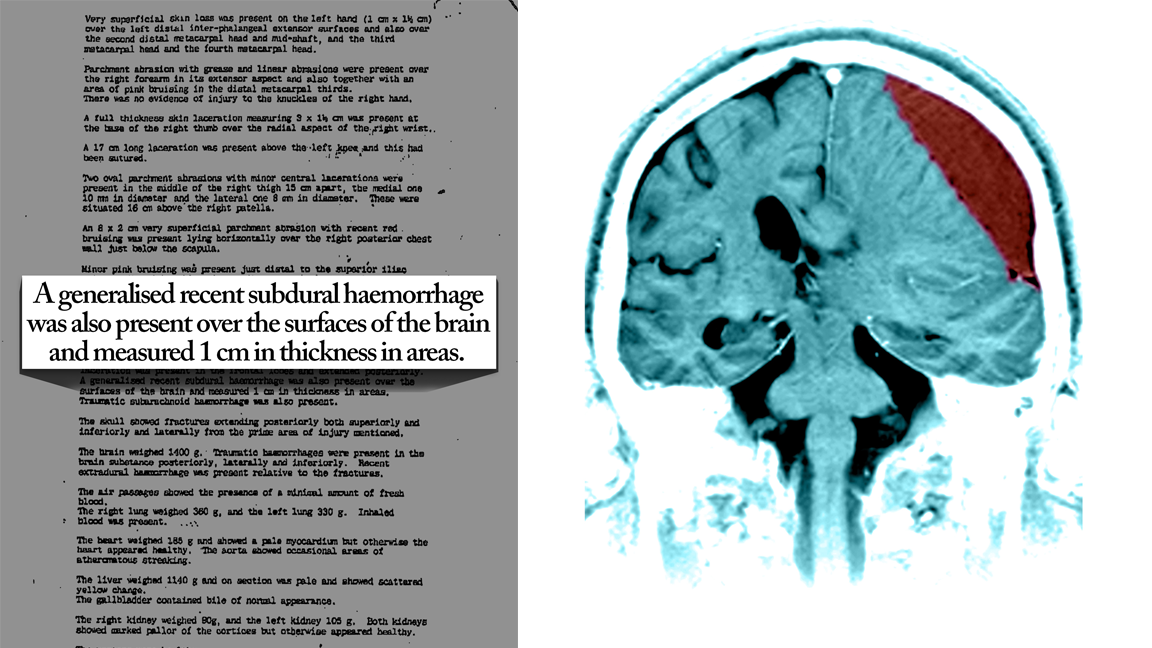

Looking at Haines’ post-mortem papers, Duflou pointed to two words - subdural haemorrhage.

“The [subdural haemorrhage] head injury is unusual in this case for somebody that’s been struck by a train,” he said. “A pedestrian struck by a train, who is killed by the train right then and there, will not have this injury. It’s a physical impossibility."

“So it must mean that something happened… in some period prior to that. And I suppose that is the central mystery of this case.”

A subdural haemorrhage is caused by a blow to the head. The force of the blow tears the blood vessels that run along the surface of the brain, which then causes a buildup of blood between the brain and the dura mater, one of the brain’s protective membrane layers.

“It’s certainly a very dangerous injury, but you see that type of injury much more from falling, from being punched [and] sustaining blows to the head, as opposed to the result of train accidents,” Duflou said.

Following a blow, a subdural haemorrhage takes at least 30 minutes to form and needs to be treated within four hours.

Duflou said it was not possible to confirm whether Haines was still conscious in the minutes or hours before he was hit by the train.

“During that time, he may have been conscious or not. But certainly as [the hematoma] gets bigger and bigger you become unconscious, and then you become comatose. So that's certainly a problem, and I think that's [the] major problem in this case - trying to explain the subdural hematoma.

“I don't think that he would have survived for any length of time with the extent of head injury that he had. So I suspect strongly there has been a head injury, and then there's been a subsequent injury. That subsequent injury could've been a blow by the train. Whether he died [from] impact with a train or not, that I can't tell.”

Oettle, who died last year, did not talk about the subdural haemorrhage – or how it may have been caused before a train hit Haines – during his time on the inquest stand in 1988.

Instead he concentrated on Haines’ second head injury, which Oettle believed was caused by the train.

“The second injury was an extradural haemorrhage, which is bleeding between the skull and the membrane covering the brain,” Duflou said.

Three hours before the train driver spotted Haines on the railway tracks, Haines had said goodbye to his girlfriend Tanya White in south Tamworth after a night out with friends.

What occurred in those three hours has remained a mystery for nearly 30 years.

Despite the inquest returning open findings, the Haines family has always maintained Mark was murdered and placed on the tracks.

Reporting by BuzzFeed News on Haines’ death has seen new witnesses come forward.

A witness broke her silence last week after almost three decades, telling BuzzFeed News that she heard a “distressed young man” begging to be left alone outside her house in the early hours of the morning Haines died.

At roughly the same time, according to the inquest testimony of White, she and Haines were walking past the house of the witness. Shortly thereafter White and Haines said goodnight and parted ways. White, who said Haines was in a good mood as he jogged off, arrived at her house a few minutes later.

A stolen Torana was found roughly a kilometre from Haines’ body. Haines could not drive, however police theorised Haines may have stolen the car, had an accident and wandered dazed onto the railway tracks with boxes from the car.

Police did not fingerprint or search the vehicle, and it was left to the elements for up to six weeks. It is not known what ultimately happened to the Torana.

Documents from 1988 obtained by BuzzFeed News detail explosive claims that Haines was killed by a group of men who were “going to teach him a lesson” because he knew too much about a marijuana crop.

Duflou said the subdural haemorrhage was not the only indication Haines had been viciously assaulted elsewhere – the lack of blood at the scene was telling.

“You would expect [lacerations] of this size to bleed, and you’d expect them to bleed quite extensively,” he said. "There should be a lot of blood around [and] I understand there wasn’t. Which is a surprise.

“I've heard that there was… rain at some stage, but you'd have to have quite soaking rain to remove all the blood.”

The lack of blood at the scene is one of several vexing questions surrounding Haines’ death.

Another relates to the positioning of Haines’ body on the sleepers between the railway tracks.

When Haines was found by the crew of a train travelling south out of Tamworth, his head was facing south and his feet facing north.

Oettle told the inquest that Haines’ extradural haemorrhage was likely caused by the front of a train, but which train remains a mystery.

Oettle said it was likely caused by the train coming in to Tamworth around 40 minutes prior to Haines being spotted by the crew on the train travelling in the opposite direction. But what is baffling is that Haines’ body had somehow been turned 180 degrees from the time he was hit by the first train to the time he was spotted by crew on the second train.

Duflou said that if Haines’ body had tumbled under the train and changed direction in the process, his injuries would likely have been far more severe.

“Once you start tumbling under a train, I think the chances are overwhelmingly high that the body starts being dismembered as it tumbles. You have very severe injuries and, I think, almost always well in excess of what is seen here.

“I don't think the injuries are of a person who has tumbled repeatedly. I suppose the alternative question is, what if there's been just a single movement? [But] under a… rapidly moving train, I'd wonder if that is possible at all.”

Another conundrum relates to a towel found underneath Haines’ head on the train tracks. Police failed to collect the towel as evidence and its whereabouts are unknown.

Duflous says it is “odd” that Haines’ head would come to rest on a towel after a train had travelled over it.

“But odd things happen. And rare things happen rarely. On the other hand, common things happen a hell of a lot more commonly, and usually the obvious explanation is the correct one. A person landing on a towel – well, maybe the towel was placed under the head. How many towels [happen to be] on railway lines? How on earth would he have landed on that towel just by pure chance?”

Adding to the contention that Haines’ body was placed on the tracks by one or more people was the lack of mud found on his clothes and shoes.

It was raining heavily on the night of Haines’ death, and the grass embankments on each side of the railway tracks had become thick with mud.

The assistant stationmaster distinctly remembered there being no mud on the teen. He said he paid particular attention to Haines’ shoes. The first police officers to attend to the body testified at the inquest that it was difficult to get to the tracks without getting muddy.

The assistant stationmaster and crew who attended the scene also said Haines’ chest was rising and that they could hear breath.

“Well if that's what they describe, and that's what in fact they saw, yes it is possible,” said Duflou. “You can survive for quite a period of time with... a subdural hemorrhage. Maybe as the body was being moved there was some gurgling and that certainly can happen.”

Duflou was sceptical, however, of the stationmaster’s claim that he detected a faint pulse in Haines.

“The detection of a pulse is actually a surprisingly hard thing to do,” said Duflou. “What you're very good at doing is feeling your own pulse. You feel the person's pulse but in fact it's in your own fingers that you're feeling it. So it wouldn't surprise me if they thought they felt a weak pulse, were they feeling their own pulse.”

Regarding Oettle’s post-mortem report, Duflou said he “did a decent job” but that more evidence should have been collected.

“I would hope that much photography would have been done. I would hope that if there were any concerns about this being a suspicious death, a suspected homicide, that significant amounts of testing would have been done, and the collection of trace evidence of various types. I would think that more microscopy of tissues would have been done to try and age injuries and that type of thing. And possibly more toxicology.

“You approach it as if it was a homicide, so you assume it’s a homicide and you move from there, and if you’ve excluded homicide, you then downgrade. You don’t downgrade early, you make absolutely sure it’s not a homicide.”

Additional reporting by Ellen Leabeater.