At 7.15pm on 28 June, a cheer went up on the Conservative benches in the House of Commons.

Theresa May’s shaky government, propped up by Northern Ireland’s DUP, had just narrowly knocked down an opposition amendment to the Queen’s Speech proposing a pay rise for the emergency services. For Tory MPs stunned by the party’s poor performance at the general election, there was sheer relief that their weakened government would be able to pass even an emaciated legislative programme.

That’s not how it came across to hundreds of thousands of people on social media.

Soon after the vote, articles appeared on popular left-wing websites portraying the Tory MPs as heartless and cynical for voting down a pay rise for nurses, firefighters, and police officers just two weeks after a fire killed an estimated 80 people in Grenfell Tower. The articles rapidly spread across Facebook and Twitter, where users posted damning verdicts on the Conservatives:

“Parasitic elitist bastards.”

“Murderous robbers.”

“Inhuman monsters.”

Four negative articles about the defeated amendment, published by Evolve Politics, the Independent, Mirror Online, and The Canary, were collectively shared nearly 500,000 times, according to analysis by BuzzFeed News of data from the social tracking company BuzzSumo, making it one of the most viral political stories of the summer. But it wasn’t close to being the only such story.

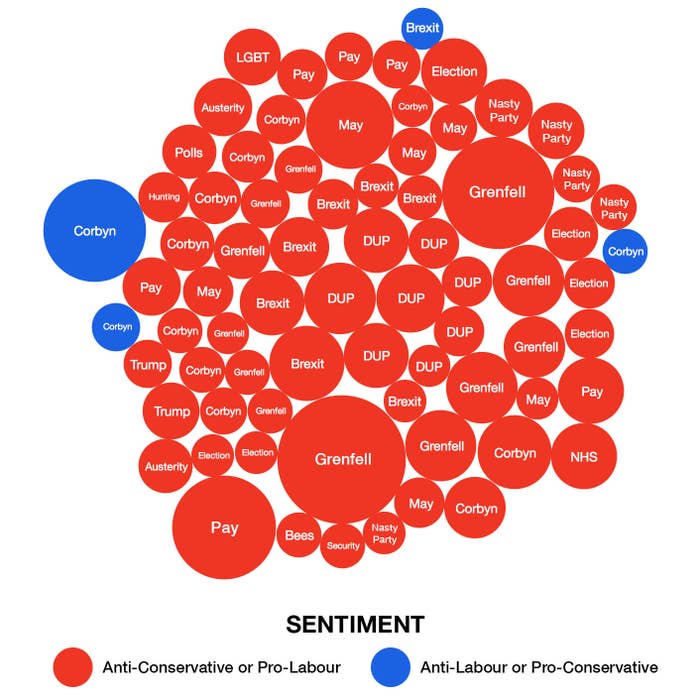

BuzzFeed News' analysis of the most-shared articles about British politics since the 8 June general election reveals that virtually nothing positive published in the media about the Conservatives has gone viral in the last three months.

Scan down the list of headlines of the most-shared stories, dig into the comments on the Facebook pages that distribute those articles across the internet, and the tone is startlingly hostile to the Tories. It’s clear there is deep resentment about their positions on austerity, public sector pay, housing, migration, and the NHS, and indignation about the government’s handling of Grenfell, its deal with the DUP, and its (abandoned) plan to revisit the ban on fox hunting.

But the anger is even deeper than that. These voters seem to think not just that the Tories have bad policies – but that they’re bad people.

On Sunday, the Conservatives will gather in Manchester for their annual party conference. It won’t be the optimistic seaside festivity Labour has just hosted in Brighton. The first order of business at the Tory conference will be an inquest into how the party blew a double-digit poll lead, squandered its Commons majority, and put itself on the brink of losing power to a 68-year-old socialist who scarcely had the backing of his own MPs a year ago. Some of the conclusions already trailed in the run-up to the conference suggest that blame will be pinned on a campaign that was too unimaginative and centralised, and a manifesto that was launched without consultation.

When the soul-searching is done, Theresa May will give a keynote speech in which she's expected to try to reboot her faltering premiership and demonstrate that she has a vision for the country beyond Brexit. In last year’s speech, in Birmingham, May pitched herself as a leader for struggling workers. This time she will have to try to reach out to the young as well.

In interviews today with Sunday newspapers, May pledged to do more for young voters including freezing university tuition fees at £9,250 a year. She will increase the income threshold at which graduates start repaying their loans to £25,000. A front page story in the Sunday Telegraph described the measures as a "revolution" in student fees, but they're a long way from Corbyn's promise to scrap the fees altogether.

Election data shows starkly the scale of the challenge May has in reaching under-35s. Corbyn’s lead over the Tories was 62% to 27% among 18- to 24-year-olds, and 56% to 27% among 25- to 34-year-olds. Those numbers terrify some Tories, who worry that the party is failing to reach the young professionals they hope would gravitate to the right as they get older, start families, and accumulate assets. The party won’t win another general election for a generation, they worry, unless it urgently does something to widen its appeal.

In the run-up to the conference, MPs and ministers have been urging 10 Downing Street to rethink its policies to address this generational gulf. In September the chancellor, Philip Hammond, told a private meeting of backbenchers that he was looking for ideas to connect with young voters for the autumn Budget. Reports have hinted at new policies on tuition fees and housing. And the government has indicated that the freeze on the pay of public sector workers imposed by George Osborne in 2010 will be eased.

But the torrent of anti-Conservative articles spreading across social media – where many people, particularly those under 35, now get their news – suggests that the party's unpopularity with the young is much deeper than even the Tory reformers realise.

“This is about identity,” says James Kirkup, a former political editor of the Daily Telegraph who now runs the Social Market Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank. “Many younger Britons just think the Conservatives are nothing like them, that Tories are rich and old and just don’t care about the lives and concerns of people who aren’t rich and old.”

David Cameron tried to “modernise” the party brand to reach beyond its traditional base. But years of austerity, the rising cost of housing, Brexit, and perceived attacks on liberal values have “retoxified” the Tories in the eyes of many young voters, Kirkup says.

And many Conservatives don’t even realise how deep this schism is, he adds.

The generational divide doesn’t just affect the Tories, Kirkup points out. Labour struggles to attract voters over 65. But right now, it seems to be Corbyn who has all the political momentum and the Tories who are fretting about losing the next election. Some are so pessimistic that they think the party will die if it doesn’t address its unpopularity among the young.

“There has been a growing electoral time-bomb ticking under them for years,” says the pollster Andrew Cooper, who was an adviser to William Hague and David Cameron. For years, the Conservatives relied on the fact that many young voters tended not to obscure their poor performance with that demographic. But that changed at this year's election. “The sudden jump in turnout among younger voters brought it suddenly into focus.”

The trope that people become Tories as they grow older and buy houses and have families was always “largely a myth”, Cooper adds, and it’s certainly not true now that so many people have been priced out of the housing market. But it’s not just about housing, Cooper says. It’s that young people seem to fundamentally dislike the party.

Cooper points to the election survey carried out by Michael Ashcroft, the pollster, author, and Tory donor. While most people who voted for the Conservatives did so because of particular factors such as Brexit or the economy, 68% of those who voted Labour did so because they trusted Labour’s motives more than those of the other parties. “They fundamentally believed that [Corbyn and Labour] are decent, good-hearted people, whereas the Tories are bad people,” Cooper says.

The same polling shows strong support among Labour voters for what Cooper refers to as an “open” worldview – a belief that multiculturalism, feminism, immigration, the green movement, and liberal social policies are forces for good – and wariness about capitalism. The bind for the Tories is that attitudes are at the opposite end of the spectrum among their core older supporters. And you can’t appeal to one group without the other noticing.

None of the small-bore policies trailed so far in the run-up to the Conservative conference are “remotely big enough to make any difference” with younger voters, Cooper says. Even if the Tories do come up with policies that have retail appeal, he adds, they won’t be trusted to implement them. “When it is coming from people whose motives are judged to be malign, even a big popular policy won’t make much impact. You can’t reposition a political brand just with a sparkly new policy.”

Some Conservative MPs worry that the party’s senior leadership, consumed by Brexit and survival, aren’t aware of the depths of their predicament.

May’s response to Corbyn’s emboldened performance at the Labour conference earlier this week – where he boldly declared that Labour “are now the political mainstream” – did not inspire much confidence. Replying to Corbyn's analysis of the limits of capitalism, which seems to be resonating with many voters right now, the prime minister gave a dry, less-than-inspiring speech about free markets at the Bank of England on Thursday. And in an interview with former Tory leader Michael Howard in The House magazine, May said the party would have to make the case for capitalism to young voters but didn’t say how she would do that, other than “getting out there and having that debate” and rethinking the party’s use of social media.

Downing Street is under pressure, including from its own back benches, to respond to Corbyn’s big-spending, vote-grabbing promises to slash tuition fees, build more houses, and give public workers pay rises. But the government is boxed in, say analysts and Whitehall insiders.

Ahead of the Budget in November, officials from Downing Street have been meeting regularly with the Treasury to figure out areas where the government could increase spending. But Hammond is a fiscal hawk who is determined not to loosen the purse strings when the economy is still fragile, the deficit is years from being eliminated, and Brexit is just over the horizon. If there is any increase in spending to mollify restless voters in the autumn, the insiders say, it won’t be much.

And that, some Tories worry, leaves the party in the worst of all positions. It is moving in Labour’s direction, conceding the political arguments to the resurgent opposition, without doing nearly enough to convince young voters that it, not Corbyn, is best-placed to improve their living standards and uphold their values.