Theresa May is facing the biggest parliamentary challenge of her time as prime minister as opposition parties prepare to thwart a crucial phase of the Brexit process.

Next week the government will lay before parliament the repeal bill, which will transfer thousands of European Union laws and rules into the domestic statute books to ensure the UK’s legal system continues to function after it leaves the union.

It is the first and most complicated of several pieces of legislation May needs to pass to lay the legal ground for Britain's withdrawal from the EU – and will kick off a long, messy political fight that will make other parliamentary arguments about Brexit seem minor by comparison, according to MPs, party strategists, and Whitehall insiders.

“This is literally a once-in-a-generation opportunity to fuck over the government,” a senior Liberal Democrat adviser told BuzzFeed News. “It’s the only way I can describe it. It’s that good. It’s going to be amazing.”

The process of legally disentangling Britain from the EU is riddled with political landmines that will both severely test May’s fragile government and consume much of parliament’s time and attention over the coming months. The stakes are incredibly high: Without legislation to ensure continuity, the UK’s legal system would be plunged into chaos when it leaves the EU, several Whitehall insiders said. The consequences of that would be so severe that the government may have to postpone Brexit if the repeal bill is defeated.

Disputes are brewing on several fronts.

MPs from Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Greens, and the SNP are preparing to table amendments to the bill that would maintain protections in EU law for consumers, workers, and the environment.

Both houses of parliament are set for heated arguments about the amount of power the legislation gives ministers to unilaterally change laws and regulations after Brexit.

The SNP will fight to have repatriated powers assigned to the devolved nations instead of Westminster.

And MPs who opposed leaving the EU, including on the Conservative back benches, are planning to use the repeal bill process to force May to soften her approach to Brexit.

“They’re going to string it up like a fucking Christmas tree with amendments,” said the Liberal Democrat adviser.

Labour promised in the election campaign that it would scrap the repeal bill if it got into power, and instead put forward a bill to maintain EU-like workers rights, equality law, consumer rights, and environmental protections after Brexit. Jeremy Corbyn told the BBC's Andrew Marr Show after the election that the repeal bill has "probably now become history".

Speaking to BuzzFeed News, a Labour policy adviser was more conciliatory than his party leader, insisting that Labour will try to improve and adjust the repeal bill rather than defeat it. But he confirmed that Labour is working on amendments that will be problematic for the prime minister.

And that is just the first stage. The full process of transitioning Britain's legal system away from the EU will take years, government lawyers have acknowledged privately.

“On the face of it, [the repeal bill] should be really boring,” said Jill Rutter, of the Institute for Government think tank. “Because it’s not really trying to change anything. It’s trying to replicate the status quo.”

In reality, Rutter said, “It’s full of constitutional landmines. And it’s got to be done by a government with an extraordinarily precarious parliamentary situation, with no majority in the House of Lords. And it’s not the only thing they have to do before Brexit.”

“I wouldn’t describe [the repeal bill] so much as a can of worms as a sack of snakes,” said James McGrory, executive director of the pro-EU campaign group Open Britain, who was a senior adviser to Nick Clegg during the coalition government of 2010-2015.

May published a white paper on the repeal bill in March, the day after she triggered Article 50, beginning the formal process of withdrawing from the EU. The bill – which was then known as the “great” repeal bill, before government lawyers insisted the name be shortened – will do three things, the government said.

First, it will repeal the 1972 European Communities Act, which formalised the UK’s membership of the union.

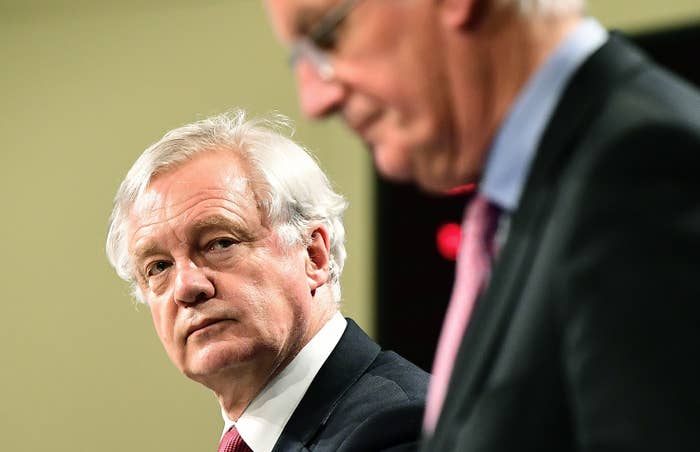

Second, it will transfer the tens of thousands of EU laws and regulations that currently apply here into UK law. Scrapping the ECA on its own would create massive legal confusion, because many of the laws followed in the UK weren’t actually set down in UK legislation but were automatically applied under the ECA. Transferring them all into UK law will ensure a “smooth and orderly” withdrawal, David Davis, the Brexit minister, said in March.

Third, the bill will give ministers powers to use “secondary legislation” to change laws after leaving. Because many of the laws and regulations that will be transferred across relate to EU institutions that will no longer apply after Brexit, ministers will have to make a huge number of tweaks in a hurry, without going through the full scrutiny of parliament. Officials estimate they will have to put forward more than 1,000 statutory instruments to make those changes.

As a technical exercise alone, this will be complicated and time-consuming, experts said. The government doesn’t even know how many EU laws there are that apply in the UK. And the domestic institutions and agencies that will underpin some of the converted law have yet to even be established.

Then there is the politics. The use of secondary legislation, or so-called Henry VIII powers – a term that refers to the way the 16th-century monarch bypassed legislators to get what he wanted – is hugely controversial. The government insists it will only use statutory instruments to make necessary adjustments to ensure the laws remain operative after Brexit, but opposition parties, interest groups, and unions are worried that ministers will be given sweeping new powers to toss out laws they don’t like without going through the full scrutiny of parliament.

Parliament, particularly the House of Lords, is uneasy about giving the executive more power in principle, observers said. That will be one early battleground. The opposition is also concerned that ministers will succumb to lobbying by corporate lobbyists and Eurosceptic hardliners (for whom escaping onerous red tape imposed by Brussels bureaucrats was a main motivation for leaving the EU) to water down protections set down in EU law for workers, consumers, and the environment.

Anticipating that, Labour is planning to put down amendments to the repeal bill guaranteeing that those rights won’t be scaled back after Brexit.

In its campaign manifesto for the general election, the party said it would drop the Conservatives’ repeal bill if it won and replace it with an “EU Rights and Protections Bill that will ensure there is no detrimental change to workers’ rights, equality law, consumer rights or environmental protections as a result of Brexit”.

A Labour aide said the party’s intention is to keep cherished legal rights, not to damage the government. “We don’t want to wreck this bill,” the aide said. “We want to make sure that it is in a good, functioning place.”

But MPs from various parties and factions, including on the government benches behind May, will see an opportunity to advance causes they believe in – including on Brexit.

So thin is May’s working majority in the Commons that only a handful of Tory MPs would need to break ranks to force her to change policy. That was underlined during the debate on the Queen’s Speech this month when the government reversed its policy on paying for Northern Irish women to have abortions in England after an amendment put down by Labour’s Stella Creasy won enough cross-party support that it looked likely to pass.

The government has tried to draft the bill in a way that makes it hard for opponents to amend. However, several sources interviewed for this article said amendments are inevitable. Some government officials believe the bill will not get through as proposed.

Not everyone in Westminster thinks it will be that difficult. Henry Newman, director of the Open Europe think tank, a former adviser to Michael Gove, believes amendments are likely but that parliament will pass the legislation. Tory rebels will be persuaded to fall in line because they could topple the government and put Jeremy Corbyn into power if they don't, Newman said. Labour will not want to collapse the bill because it would be seen as plunging the country into legal chaos and voting against Brexit, in defiance of the public will.

“I think it will get through amended, but it’ll take so long, and it’ll be inch-by-inch,” the Liberal Democrat adviser said. “It’ll take a lot longer than they think it will take.”

If it does pass, the Lib Dems will then try to frustrate the government by challenging every one of the statutory instruments the government puts down to amend the EU-derived laws. The party's chief whip threatened before the election that it would "grind the government's agenda to a standstill" by trying to force a vote on each of the statutory instruments.

That threat was taken so seriously in Number 10 that May cited it as one of her main reasons for calling the general election in April.

David Davis, the Brexit minister, told cabinet colleagues on Tuesday that the bill will be laid before parliament next week, although the Commons is not expected to debate the legislation until October. A spokesperson for the Department for Exiting the European Union would not confirm the timing.

The government is understood to be hoping to have the bill passed by the end of the year, but a number of Whitehall officials who spoke to BuzzFeed News believe that is far too optimistic.

If May gets the repeal bill through, she will then have seven other Brexit-related bills to get through, setting out the legal basis for new systems of immigration, trade, customs, and nuclear safeguards. Each in themselves will be contentious. And time is quickly running out.