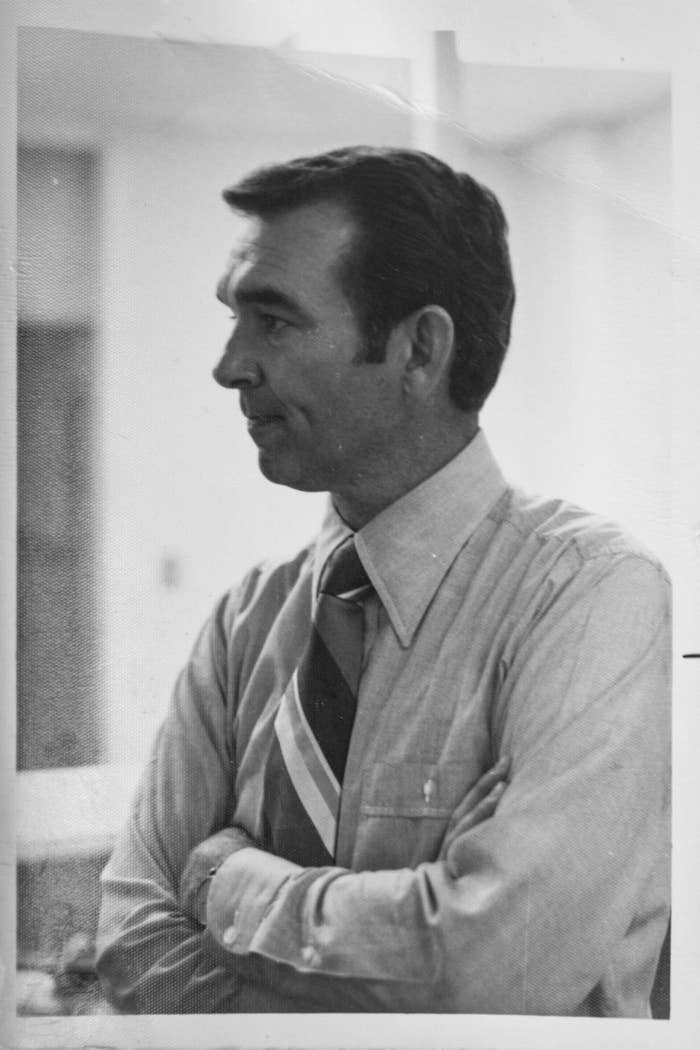

As a child, Kari Brandenburg dreamed of becoming district attorney. Her father, James Brandenburg, worked as a prosecutor for eight years in the 1960s before becoming Bernalillo County district attorney in the 1970s, and her earliest memories were in the living room of their Albuquerque home in the evenings, her father setting a briefcase full of case files on the table, and when he went into the bedroom to change, she pounced, popping it open and looking through the gruesome crime scene photos. “My sister thought I was going to be a serial killer,” she said.

During breaks from school, she accompanied her father to work. She loved watching him in the courtroom and she begged him to let her skip class on trial days. She savored the thrill of police officers knocking on their door late at night, asking him to approve an urgent warrant. “They looked like heroes,” she once told a local reporter.

At first her father welcomed her interest in his profession — how cute his little girl’s obsession with this serious, button-down, bloody, male-dominated world. But as her obsession carried on into high school and college, he grew worried. He did not want his daughter to become a lawyer and he did not think it was even possible for her to become a DA. He once told a local reporter, “I’ve always felt that a woman is at a disadvantage when you’re in the art of persuasion.” Judges and jurors, he believed, “are more inclined to give credibility to the man.”

She became a lawyer anyway, and in 2001 she became the first woman to serve as district attorney in Bernalillo County, the biggest county in New Mexico. She brought home high-profile convictions and rose to statewide prominence. She won every election she ran in, four in a row, establishing herself as the longest-serving DA in county history. She aimed to hold the seat for six terms, she once declared, and many believed that it was hers to keep for as long as she wanted. She was a golden child of the state’s Democratic Party machine. Newspaper columnists and the local political set floated her name for Congress and governor.

And now, on a bright morning in March, all those good years were rushing back. Kari Brandenburg stood behind a podium and reminded everybody at the press conference how far she had come. “I remember back in the days when I had to convince people I was a lawyer,” she said. “I had a client: ‘Are you really a lawyer?’ ‘I promise I am.’”

She paused for laughter that did not come. She looked around at the barren ground-floor room of the district attorney's office building, with empty walls, fluorescent lights, and a window cloaked by gray blinds. The half dozen or so reporters sat evenly spaced out at the long wooden tables in front of the television cameras along the wall in the back. She did not maintain the stoic, self-righteous demeanor common among district attorneys. No, Kari Brandenburg was bubbly and warm, even when she talked about “the challenges.”

This, her 16th year in office, had been a hard year. The crime rate had increased. Thousands of cases had been dismissed because of her office’s mismanagement. Her son was in prison. Two of her top deputies had been diagnosed with cancer and were currently undergoing chemotherapy. And she was no longer on speaking terms with the city's police chief.

She had done so much for the Albuquerque Police Department! She had locked up men who shot at officers, defended officers when they faced scandal, protected officers when they killed civilians. She had gone nearly 14 years without charging a single officer for a fatal shooting. And so when she decided to charge two of them with murder in January 2015, she did not expect her longtime allies to turn on her. But indeed those longtime allies went on to orchestrate “a complete snow job against her,” as former Albuquerque police Sgt. Tom Grover put it. They attacked her reputation. They stripped from her the biggest case of her career. They resisted the authority of her office. And, she told those around her, they threatened her family’s safety. It was a surreal turn of events: a district attorney scared of her city’s police department.

The challenges wore her down, and beneath the warm smile and energetic voice was a weary, defeated woman.

“I bet you all don’t know what I’m going to say next,” she said to the room, arms up and palms open in mock anticipation. “I want you all to know that I’m not going to be running for a fifth term for district attorney.”

In her mind, she was paying the price for charging those officers with murder. She had stood up to a stubborn police department at a time of national unrest, trudging forward despite the political consequences. In her mind, she was a martyr, made to suffer for doing what was right. When a reporter asked why she was stepping down, she offered a simple answer: “I’m tired.”

When her father was the DA in the late 1970s, around 20 lawyers worked in the office and fewer than 1,500 inmates were locked up in New Mexico state prisons. By then, America’s violent crime rate had risen for 20 years and the tough-on-crime era was dawning. Over the following decades, state and federal politicians across the country passed laws that led to more arrests and longer sentences and expanded the criminal justice system. When Brandenburg took office in 2001, around 100 lawyers worked in the office and the state’s prisons held nearly 5,000 inmates. By her third term, the prison population had jumped to around 7,000.

But while the criminal justice system transformed dramatically from James’ first day in office to Kari’s, the relationship between police and prosecutors remained steady. Officers investigated crimes, caught the suspects, then handed their files over to prosecutors, who turned those files into believable and constitutional narratives for a jury’s consumption. The two agencies have served as allies throughout the history of modern American law enforcement. This relationship breeds conflicts of interest, and the recent past is cluttered with examples of prosecutors granting special leniency to their allies in blue facing criminal allegations. For many years this state of affairs played on without ground-shaking scrutiny.

Ferguson changed things. The national outrage sparked by the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in August 2014 pushed police shootings into the center stage of public discourse. Prosecutors faced heightened attention for how they handled these cases. This new political landscape has created a growing rift between police and prosecutors across the country. Now many district attorneys find themselves caught between the public's desire for police accountability and their law enforcement partner’s long-held expectations for special treatment.

It has become politically beneficial to hold police accountable in many cities across post-Ferguson America. Earlier this year, during the first election cycle of this new era, voters punished incumbents who failed to bring charges against officers involved in questionable shootings. Cuyahoga County Prosecutor Tim McGinty, who oversaw the Tamir Rice case, lost his primary race by 11%. Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez, who oversaw the Laquan McDonald case, lost her primary race by 30%.

Meanwhile, mayors in Baltimore, San Francisco, and Chicago gave in to protesters’ calls to fire their police chiefs. The ousting of these chiefs and prosecutors has emerged as the most tangible impact yet of the Black Lives Matter movement, which was born in 2013 after George Zimmerman was found not guilty of murdering Trayvon Martin and rose to national prominence during the Ferguson protests. In response, police departments and unions have closed ranks and fought back.

Baltimore police turned against State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby, the daughter of two cops, after she charged six officers for the death of Freddie Gray in April 2015. A police union magazine published a column accusing her mother of drug use and her father of robbery. “Nobody wants to work” on Mosby’s security detail, one Baltimore cop said. “I haven’t found a cop who supports Mosby.”

San Francisco police turned against District Attorney George Gascón, a former police chief, after he led a blue-ribbon panel investigating racial bias in the department in February 2016. The police union president claimed that he had heard Gascón make racist remarks at a dinner six years earlier. A union press release blamed an uptick in property crime on Gascón, who “instead of fighting a war on crime, is fighting a war on the police department.”

“A shift has been made to where a prosecutor has a responsibility first and foremost to the community rather than aligning themselves solely with law enforcement,” said Ahmad Assed, a defense attorney in Albuquerque. “The issue now is how we are going to have law enforcement agencies work hand in hand with prosecutors. Is it now too much of an uncomfortable relationship?”

"We learned that sometimes we are punished for doing the right thing.”

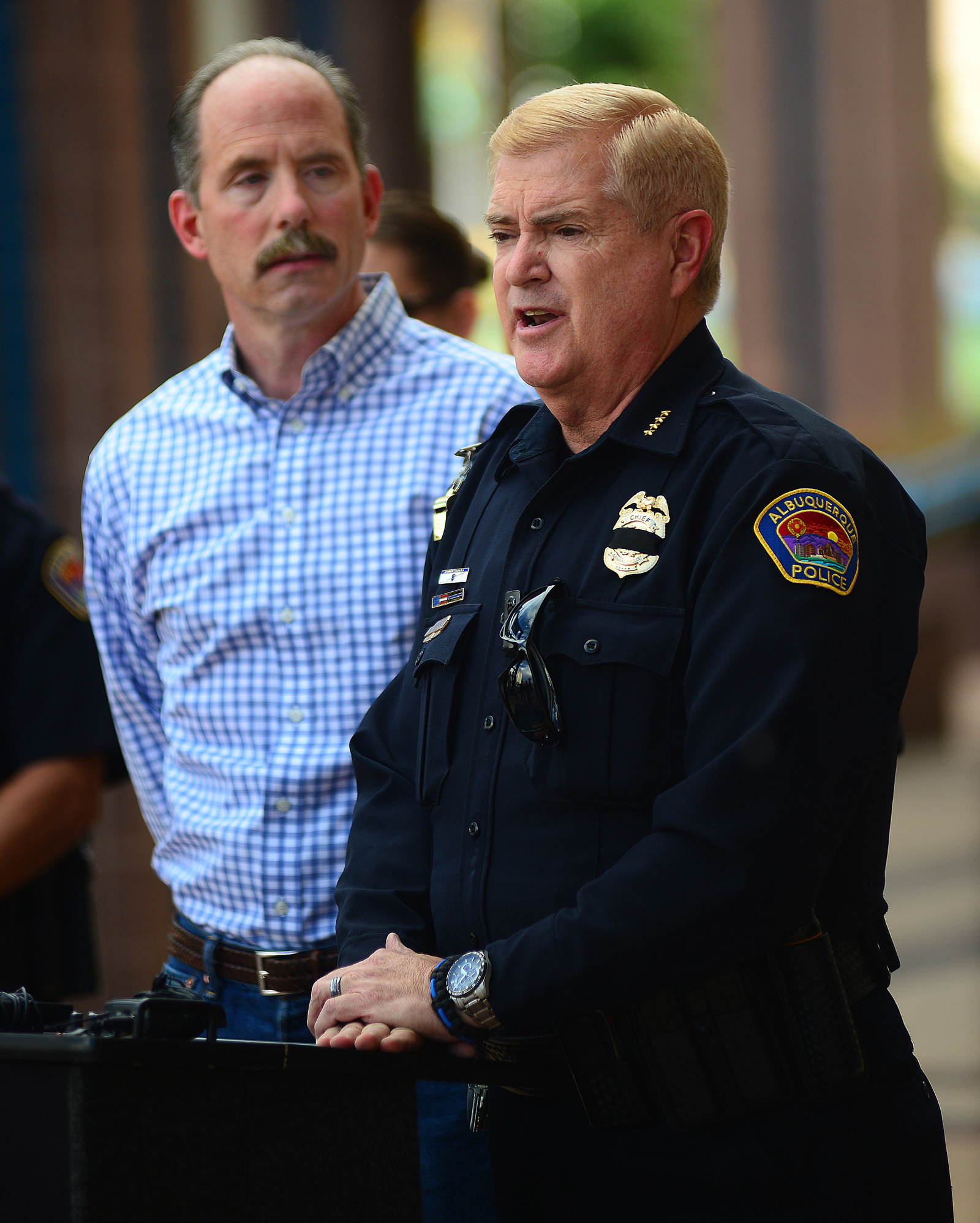

This question burns hottest in Albuquerque, where the rift between police and prosecutors is more extreme than anywhere else in the country. Brandenburg was quick to note that she has no beef with rank-and-file officers. She was just as quick to note how little respect she has for Police Chief Gorden Eden and other high-level police officials, who she said “allowed themselves to be used,” and just as quick to note what she thinks of Albuquerque Mayor Richard Berry, of whom she said: “I think he’s a psychopath.”

She charged two officers for fatally shooting James Boyd in March 2014.“That had a lot of consequences for me,” she said. “Some of us lost our belief in the system, the idea that as long as you do the right thing, you won’t be accused of doing wrong. But we learned that sometimes we are punished for doing the right thing.”

Her clash with the police department was a shock to many of her allies, who observed that she had gone 14 years without major controversy to that point. A few of those allies sat with her for dinner at a restaurant in the Sandia Casino on the outskirts of town one evening in May, and among that friendly company, the discussion quickly turned to her tensions with the Albuquerque Police Department.

“She hit a brick wall when she tried to hold police accountable,” said Pete Dinelli, a political mainstay who over the years has served as a city councilor, deputy city attorney, assistant attorney general, chief deputy district attorney, state judge, and director of public safety. “We really worked hard to build that department and now it’s one of the worst in the country.”

“I think they believed they would keep hitting me in the stomach and at some point I would stop getting up,” Brandenburg said.

“It’s an us-versus-them dynamic,” said Greg Payne, a former city councilor and state house representative. “It is deeply embedded in the culture of that department.”

“They thought that they could intimidate me so that I would resign,” Brandenburg said. “Have you ever heard of a police department try to take over a DA’s office?”

“Police have viewed prosecutors as extensions of themselves,” Payne said. “And for them that means any wrongdoing in their department has to be swept under the rug by the DA. They went after you because you didn’t do what they wanted you to do.”

Brandenburg shook her head, raised her eyebrows, cracked an astonished smile, and said, “Can you believe how dangerous it would be if police departments start running district attorney’s offices?”

How strange to hear District Attorney Kari Brandenburg deem the Albuquerque Police Department an adversary when for 14 years she had served as its loyal ally. “She spent her entire career carrying their water for them,” said David Correia, an American studies professor at the University of New Mexico.

She was good friends with the previous police chief, Ray Schultz, who held the job for eight years until July 2013. They regularly went to lunch and met to discuss big cases. Their top deputies convened on a monthly basis. “We worked very well together,” Schultz said. “It’s important to keep a good relationship between the two offices.”

This relationship was especially beneficial for the police department as the number of police shootings dramatically increased. According to Dinelli, a city attorney at the time, this rise in police-induced bloodshed was born on August 18, 2005, the day officers Richard Smith and Michael King were fatally shot on the job. In a meeting about the incident, Dinelli said, “I remember Schultz saying, ‘This’ll never happen on my watch again.’ So they trained officers to become more aggressive. It took about five years for all of that to seep into the culture of the department and 2010 is when you saw the seeds that had been planted.”

From 1986 to 2006, APD officers killed, on average, about three people per year. In 2010, officers fatally shot nine people and wounded five more. From 2010 through the end of 2014, officers shot 41 people, killing 28 of them. Over that stretch, Albuquerque's rate of fatal police shootings per capita was eight times higher than New York City’s and twice as high as Chicago’s. Many of these shootings were questionable enough that the city paid out $30 million in civil judgments and settlements. The Department of Justice opened an investigation and concluded that “a majority” of the city’s recent police shootings were unconstitutional. "Albuquerque police officers shot and killed civilians who did not pose an imminent threat," the DOJ’s report stated. “A lack of accountability in the use of excessive force promotes an acceptance of disproportionate and aggressive behavior towards residents.”

Through it all, Brandenburg did not charge any officers for any shootings. “The DA’s office clearing people led to more and more shootings because they kept getting away with them,” said Joe Fine, a local civil rights attorney. Brandenburg handled police shootings by sending the cases to “investigatory” grand juries, which operate differently from traditional grand juries. In a traditional grand jury, a prosecutor presents a selection of evidence, recommends a charge, and deliberately leads the jurors to indict the defendant on that charge. There is no defense attorney in the room. Under these circumstances, New York Court of Appeals Judge Sol Wachtler famously joked, any good prosecutor can get a grand jury to “indict a ham sandwich.”

She recalled one woman who stopped her in the grocery store: “She told me she thought it was good the cops were shooting these criminals.”

In the “investigatory” grand juries for police shootings, Brandenburg’s prosecutors did not give jurors the power to indict on criminal charges. Instead, the prosecutor told the jurors that they were tasked with determining whether the shooting was “justified” or “unjustified.” If the grand jury ruled “unjustified,” then Brandenburg would take the case to a traditional grand jury for a potential indictment. The Bernalillo County District Attorney’s Office had used this process for police shootings since the late 1980s and over that time not a single grand jury returned an “unjustified” verdict. Prosecutors met with officers before the hearings, guided them through their justifications on the stand, and rarely challenged their story.

Brandenburg argued that because investigatory grand juries have subpoena power and hear testimony under oath, they are more fit than prosecutors to figure out whether a shooting is justified. She defends the practice to this day, even though in 2013 a panel of judges ordered that her office end it. “The appearance of a lack of impartiality is impossible to avoid, especially given that the procedure is used only for police officers and specifically limited to officer-involved shootings,” the judges wrote in a letter to Brandenburg.

The new process required prosecutors to decide for themselves whether there is probable cause to charge an officer for a crime. Brandenburg’s office took on 100 to 200 hours of additional work to review each police shooting, she said. Yet the new process brought the same old results. From January 2013 through February 2014, APD officers shot nine people. Brandenburg’s office did not find probable cause to prosecute any of them. “The case law is pretty liberal in giving cops broad discretion,” Brandenburg said. “If we don’t think we can win the case, we’re wasting everybody’s time. We’re not saying that everything was appropriate. We’re just saying that we can’t move forward with the prosecution.”

The numbers backed her up, she said. She recalled a Washington Post story that found that of the thousands of officers involved in shootings over the last decade, only 54 were charged. “This is pretty universal,” she said. “This doesn’t mean the system’s wrong. I think police officers need broader discretion.” She believed that most of her constituents agreed with her. She recalled one woman who stopped her in the grocery store: “She told me she thought it was good the cops were shooting these criminals.”

Albuquerque is an isolated place where change comes slow. With half a million residents, it is the biggest city in the state, making up 80% of Bernalillo County’s population, but it feels like a place forgotten about, choked off from everywhere else. Faded and chipped pastel buildings line the commercial districts. On Central Avenue, part of Route 66, broken neon signs from demolished buildings stand tall on the sidewalks in front of vacant lots. Empty storefronts dominate the big mall in the center of town, where the parking lot is mostly empty even at rush hour. Homeless men and women sit on curbs in fast-food parking lots, push shopping carts down major thoroughfares, and sit at the base of the highway exit ramps holding cardboard signs.

“If you drive out of town, it’ll be desert with a couple of exits, then desert,” said Tom Grover, the former APD sergeant who now works as a lawyer. “And when you have that sort of environment, people get very entrenched in their power structure.”

In Albuquerque, around 20% of residents live below the poverty line. Many of them live in the southern part of the city, in squat houses made of stucco or cement blocks. The rich folks live in the northeast pocket at the base of the Sandia Mountains, and that is where Kari Brandenburg lives, in a gated neighborhood, in a two-story, high-ceilinged house beside a golf course. She has lived here for 22 years, but in recent years she has lived here alone. Her four children are adults now. She adopted the three oldest with her second husband and the youngest with her third husband. She considered adopting more kids, but decided against it. “The police department — if a kid fell and hurt their knee, they’d probably charge me with child abuse,” she said.

Her children were still young when she first ran for office. She was an unknown candidate then, a veteran lawyer with a vaguely familiar last name who had done 20 years of criminal defense work after graduating from Southern Methodist University law school. Her first race was close. Two months before the November election, polls showed her tied with Skip Vernon, the Republican leader of the state Senate. Then, weeks before the election, Brandenburg revealed that she received a love note from Vernon: "Even if we could be together we probably wouldn't get along but I would keep you entertained and thinking,” the email began. Vernon claimed he had meant to send the email to his wife. Brandenburg accused him of sexual harassment. She won the election by 12%. It would be her closest race over the next 16 years.

A month after the 2000 election, just days before she took office, her second husband died from cancer. Her oldest son, Justin, who was 12 at the time and had watched his father quickly deteriorate, took it the hardest. A year later, her third husband died from an infection. She wondered if she should quit her job. But within days she was back in the office “putting in her usual 50 to 60 hours a week,” Chief Deputy DA Debbie DePaulo recalled. “She just plowed through.”

She brought a wave of changes to the office. She allowed her lawyers to have unframed pictures at their desk. She relaxed the dress code, and soon lawyers in cowboy boots and polo shirts and long flowy dresses prowled the halls. She made sex jokes in staff meetings and played pranks, like hiding a fart machine under a chair.

Over the years, a nanny helped out with the children on weekdays, though sometimes Brandenburg brought the older ones to watch her trials — often headline events in which she convicted defendants accused of high-profile crimes. One of her daughters went on to become a lawyer. Another daughter works in retail. Her youngest son attends college in California. Justin ended up in prison.

A reporter asked Brandenburg if she should have been home with her kids instead of working long hours at this high-profile job.

His troubles stemmed from his heroin addiction, which seemed to take hold of him by the time he was 18. He was arrested for DWI twice and for shoplifting three times. Each time, there was his mugshot on the news. “They had him on there like he was a serial killer,” she said. “And it was because of me and my job.”

She sent him to rehab several times, but his troubles continued. Eventually, she kicked him out of the house. He left with a sleeping bag and a backpack filled with his few possessions. “As a mother, it’s just a feeling of being totally helpless,” she said. “I can’t tell you how horrible those days were.”

On June 28, 2013, Justin stole an Xbox, a PlayStation 3, and several video games and DVDs from the home of his friends Ryan Sena and Shane Anaya. Sena and Anaya reported the theft to the police and named Justin as the likely suspect because he had been at their house earlier that day. Sena contacted Brandenburg on Facebook and told her what happened. Over the following weeks, they exchanged friendly messages. “Your family is in my prayers,” Sena wrote. Brandenburg told Sena, “Let me know the value of the things stolen as I will try to work on it.”

On July 7, 2013, Justin stole a handgun from the home of his friends Andrew and Victoria Barros. They reported it to the police and said that they believed Justin was the culprit because he had stolen from them before. The next day, Andrew Barros sent a Facebook message to Brandenburg. “I am glad you reported the gun stolen,” Brandenburg wrote back. “You needed to do that to protect yourselves.” She told Barros that she was worried that a felony conviction would ruin Justin’s life and that she hoped he wouldn’t end up in prison. She offered to compensate them for the lost property.

On August 6, she wrote Barros a check for $800. But she did not reimburse Sena and Anaya because, she told them, she did not have enough money. The Albuquerque Police Department opened an investigation into Brandenburg in October.

As with all of Justin’s legal troubles, Brandenburg did not handle the prosecution. The DA of a neighboring county handled the cases. Justin pleaded guilty and a judge sentenced him to three years in prison. Brandenburg had prosecuted many of the inmates he was locked up with. Prison officials sent him to solitary confinement for his safety.

At a news conference, a reporter asked Brandenburg if she should have been home with her kids instead of working long hours at this high-profile job. In her head, she seethed at the question. A male DA, she thought, would never have to defend his decisions as a father.

The video, she said, appalled her.

An officer’s helmet camera captured what happened in the foothills of the Sandia Mountains on March 16, 2014. More than a dozen officers faced off with 38-year-old James Boyd, a homeless man with schizophrenia who had been illegally camping in the area. The police report claimed that Boyd had escalated the situation by threatening the officers with two knives, but the video showed that Boyd was not holding anything when officers fired a stun grenade and then sent a police dog at him. Only then did Boyd pull out the knives. He was turning away from the officers when six shots were fired, killing him.

Brandenburg said that she was sickened when she met with police officials and heard their explanations. “I couldn't sit there and listen to why it happened,” she said. “I just walked out of it. I didn’t have all of the info and so I didn’t want to say it was bullshit, but it was hitting me that something wasn’t right.”

"I didn’t want to say it was bullshit, but it was hitting me that something wasn’t right.”

Unlike previous police shootings, she said, this one had a clear video that showed clear wrongdoing. It was the first time in her 14 years that she had enough evidence to prosecute, she said. Over the next six months, though, she did not file any charges because, she said, she was waiting for the results of the APD’s internal investigation, which was not completed until September. Her decision to charge the officers, she said, was based solely on the facts of the case and had nothing to do with any external pressures. “I don’t read the newspaper and I don’t watch the news,” she said. “It was just the right thing to do.”

The external pressures, though, were heavy and constant. Within weeks of the shooting, local news outlets were showing the footage and protesters were marching down Central Avenue, calling on the mayor and the police chief to step down. They rallied outside her office and demanded criminal charges. An Albuquerque Journal poll in March showed that nearly two-thirds of voters did not have confidence in the police department, which remained under federal review. At one April gathering, protesters shut down traffic and threw rocks at police officers, who arrived in riot gear and on horses and sprayed tear gas to disperse them. In June, CNN picked up the footage of the shooting, and soon Brandenburg found herself under the largest national spotlight of her career.

Then, on July 17, a New York City police officer killed 43-year-old Eric Garner with a chokehold in Staten Island. Less than a month later, on August 9, a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, fatally shot Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old. Ferguson erupted in protests and fires. A sea of outrage swept across the country and, suddenly, police shootings became the biggest story in America. “That forced Brandenburg’s hand,” said former APD Sgt. Dan Klein, who spent 20 years in the department before retiring in 2003.

In November, the prosecutor in Ferguson announced that he had failed to get a grand jury to indict the officer who killed Brown, sparking heated protests in that city. In December, the prosecutor in Staten Island announced that he had failed to get a grand jury to indict the officer who killed Garner. A few weeks later, in January 2015, Brandenburg announced that she was filing murder charges against APD Officers Keith Sandy and Dominique Perez, who each fired three shots at Boyd. “I have a job to do and I’m doing it,” she said at the press conference. “Unlike Ferguson and unlike in New York City,” she declared, she would bring the charges herself, in a preliminary hearing, rather than leaving it to a grand jury.

By then, the APD officers had already known for months that the charges were coming. Brandenburg had finalized her decision back in October and spent the next two months strengthening the case before the public announcement. On October 7, she had called Fred Maurer, the police union’s lawyer, to inform him that she was planning to file murder charges against Sandy and Perez. And so it was in October when police officials began their plan for revenge.

While investigating Justin’s alleged burglaries in summer 2013, officers learned that Brandenburg had contacted his victims. Detective David Nix was tasked with figuring out whether Brandenburg had tried to pressure them to not call the police. Andrew and Victoria Barros told Nix that Brandenburg did not pressure them. But Sena and Anaya, the victims whom Brandenburg did not reimburse, claimed that Brandenburg told them she would pay them only if they did not report the crime. Brandenburg said this in a phone conversation from a blocked number, Sena claimed. But investigators checked Sena’s phone records and found no such calls in the months following the theft. Nix did not seem to find Sena’s allegations credible.

On October 17, 2013, after Nix interviewed the burglary victims, he spoke to Sgt. Soren Ericksen about the case, a conversation that was captured on an audio recorder on Nix’s belt. Nix expressed doubts about the case.

“There might be charges, they’re super weak, probably not gonna go anywhere, but it’s gonna destroy a career,” Ericksen said. “Who are we trying to get here? Kari or Justin?”

“Justin,” Nix replied.

Nix later told the New Mexico Office of the Attorney General that he had finished the investigation into Brandenburg by the end of July 2014. Brandenburg said that sources within the department told her that the case was closed.

But then on November 25, 2014, weeks after Brandenburg informed the police union of the charges against the officers, Nix, under orders from superiors, dropped off the investigation’s files to the Office of the Attorney General, along with a letter stating that the department believed it had probable cause to charge Brandenburg with bribery and intimidation of a witness, both felonies. Some local officials and protesters called on her to step down.

“What was surprising was how obvious and transparent it was that they were gunning for Kari,” said Tom Grover, the former APD sergeant. “She went into an area they didn’t want her to go into and so they went forward with these trumped-up charges.”

Attorney General Hector Balderas found the circumstances suspicious. “The timing of APD’s decision to turn over its investigation to the Office of the Attorney General raises questions about APD’s motivations,” Balderas said in a letter to Chief Eden. After reviewing the case, Balderas dismissed the allegations, concluded that Brandenburg had not committed a crime, and stated in his report that the police department had been “politically motivated.”

Brandenburg believed that Mayor Berry was behind it. Many in the state assumed that Berry had aspirations for governor and Brandenburg stood out as a potential rival for that job. Dinelli and Correia believed that it was a collaborative effort between the mayor and police chief — the two men had held a meeting about the investigation shortly before it was forwarded to the attorney general, according to several local sources. “The mayor of Albuquerque is interested in protecting the interest of the police department,” Correia said. Berry and Eden declined multiple interview requests for this story.

Though the investigation quickly fizzled out, it had a direct impact on Brandenburg’s career. Lawyers for Sandy and Perez argued in court that Brandenburg’s office could not prosecute a case against APD officers because she had been under APD investigation, and therefore she would be biased against the department. Speaking on behalf of the mayor’s office, Chief Administrative Officer Rob Perry declared that Brandenburg had a conflict of interest. Police union leaders echoed these statements.

The judge overseeing the case ruled in favor of the officers and ordered Brandenburg to find another lawyer to handle the case. Even though Brandenburg was not necessarily biased, the judge stated, “the media’s connection of the two unrelated investigations” had created “an appearance of conflict.” “It was kind of brilliant,” Brandenburg said. “I’d have no option but to never charge a police officer for a shooting.”

It was not so easy to find a special prosecutor. Every other district attorney in the state turned down her request to consider the case — she said that they claimed to not have the resources to take it on, but she suspected they just didn’t want to deal with the politics of it. “The police and the city knew all that and they were hoping that the case would disintegrate,” Dinelli said. Eventually, local attorney Randi McGinn, regarded as one of the best private attorneys in the city, agreed to take on the case. She had turned down Brandenburg’s request at first, but when Brandenburg called her back days later explaining that everybody she asked had said no, she relented. “That can’t be how it works,” McGinn said. “Just because they’re police officers, nobody is willing to take it.”

The police department had effectively stripped from Brandenburg the biggest case of her career.

“The underlying motivation was to get her bumped off the case,” said Dinelli. “But it was more than that. They were telling her: You’re no longer one of us.”

The retaliation against Brandenburg was brazen and clear and part of a long history.

In the early 1980s, a lawsuit revealed that the Albuquerque Police Department had been keeping files on politicians, judges, attorneys, and other prominent locals. The exact contents of these documents never became public. The department burned the files. In 1987, after a state representative helped defeat a bill proposing an officer’s bill of rights, two APD officers left on his desk a black rose and a drawing of a man with a knife in his back. Local officials, led by then-councilor Pete Dinelli, pushed for civilian oversight of the APD in the late ’80s. During city council meetings, a row of uniformed officers would stand in the back of the room, Dinelli recalled. The night before a vote for a bill establishing an independent police oversight committee, then-Chief Sam Baca called Councilor Dinelli at home. Baca, Dinelli said, told him to withdraw the legislation. “I do not have control of my police officers after hours,” Dinelli remembered Baca saying. “I don’t know how they will react to this.” (Baca has denied making this threat; the bill passed anyway.)

“The police in Albuquerque have a pattern of attempting to intimidate people,” said Correia, the University of New Mexico professor. “They make it clear that we know who you are and we’re watching you.”

In recent years, as Correia emerged as a vocal critic of the department, he began to notice police cars following him home, he said. “They would just pull into my driveway and sit there,” he said. When Randi McGinn took on the Boyd police shooting case, she said, “My friends in law enforcement asked if Kari was gonna hire me a bodyguard and if I was gonna start wearing a bulletproof vest, because the cops are gonna come after you.”

On January 13, 2015, the day after Brandenburg publicly announced the charges against Perez and Sandy, two APD officers fatally shot a man during a foot chase. Following long-established protocol, Brandenburg sent a representative from her office, Chief Deputy DA Sylvia Martinez, to the scene. In all previous police shootings during Brandenburg’s tenure, her deputy would attend the police briefings and participate in the investigation. But on this day, APD officers barred Martinez from the scene and Deputy City Attorney Kathryn Levy told her that she was not allowed into the briefing. The episode sent a shiver through Brandenburg’s office. Employees began to wonder how far the department would go in their quest to get back at Brandenburg. “All of us started to be on edge and almost a little paranoid,” said Chief Deputy DA DePaulo. “Is somebody following me? Is somebody watching me? Could I be stopped and have something planted on me?”

One of Brandenburg’s friends in the department told her to “be really careful,” she said, and warned that officers might be following her. Another told her to turn on the voice recorder on her phone if she was ever pulled over by police, she said. She installed security cameras around her house. “I wouldn’t go out after dark if I were alone,” she said. “I was really worried about my kids being in town.” She would not say what, exactly, she feared would happen to her, only that she "was concerned about everything.”

“They were delivering a message: This is what will happen to you if you step out. We’ll investigate you. We’ll embarrass you.”

More than a year later, Brandenburg was still nervous. Those who knew her noticed that the APD’s retaliation seemed to have its intended effect. “They were delivering a message not just to her but to everyone else and to whoever is the next DA,” Correia said. “Saying: This is what will happen to you if you step out. We’ll investigate you. We’ll embarrass you.”

Her office slipped into a downward spiral in the months following the Boyd murder charges.

The backlog of police shooting cases grew. Prosecutorial delays led to even longer pretrial detention times. Judges were dismissing thousands of cases because prosecutors were missing deadlines to file evidence in court. “She was a very popular district attorney for a long time,” local defense attorney Assed said. “She doesn’t enjoy that reputation anymore in this last term. A lot of people think that she’s checked out.”

At a recent staff meeting, Brandenburg and her deputies addressed the crises that weighed down the office. Brandenburg blamed the APD. Officers, she claimed, took too long to hand over case files to prosecutors. But what could Brandenburg and her staff do about it? Perhaps, Brandenburg suggested, they could send a letter to Chief Eden asking him to speed up investigation times.

“It’s not going to do anything,” DePaulo said with a shrug.

Everybody agreed. Though Brandenburg and Eden had gone to high school together and were friends when he became police chief in 2014, they no longer talked. But Brandenburg suggested that they write it anyway so that there would be a public record of her office trying to fix the problem, something she could point to when people asked her why indictment numbers were down. There was no discussion of collaborating with the department on a possible solution to the problem. The department, Brandenburg believed, had already shown there was no hope for that. In March 2015, Greg Buchanan, a 24-year-old white man, fatally shot Jaquise Lewis, a 17-year-old black kid, at a skate park. Buchanan claimed Lewis had pointed a gun at him, though no gun was found at the scene. Brandenburg hoped to move on the case quickly. The police department announced that they’d have the file to the DA’s office by October 2015. The deadline passed. Brandenburg wrote Eden letters “requesting all the reports.” They never came. Nearly a year later, her office still had not received the file.

“She’s at the mercy of the APD,” Dinelli said. “It’s clear the APD does not like her and they’re not going to cooperate with her.”

One morning in May, with seven months left in office, Brandenburg met with victims’ advocates who had come to discuss her conviction rate. The conversation stayed on topic until Brandenburg began describing the challenges her office faced, stating in a matter-of-fact tone, “You know, if you walk around the office, we’re at war and these bombs are going off in the trenches all around us.”

In the year and a half since the murder charges, she has peppered her speeches and dialogue with this sort of insurgent and vague rhetoric. In a press conference last year, she spoke about a “city in crisis,” and when reporters asked her to be more specific, she said, hesitantly, as if disclosing a secret she shouldn’t be disclosing, that she was referring to “much of the distrust in the police department.”

“I have had officers come to me and tell me things that cause me not to sleep at night and I have asked them to come forward and that we will protect them,” she continued. “People are afraid.” The reporters pressed her for details. “You guys are asking me questions I don’t want to answer,” she said. “Because I don’t want to be accused of retaliating.”

“They went after Kari with knives and she responded with squirt guns.”

The way Brandenburg sees it, she has acted with righteousness, an innocent and honorable victim of conspiracy and sabotage. Yet even her allies believe that she has cowered from her enemies. Her war was one-sided, the bombs going off only in her trenches, and those who punished Brandenburg have faced no consequences. “She just lets them beat on her with no response,” said former APD Sgt. Dan Klein. “They went after Kari with knives and she responded with squirt guns.”

The Albuquerque Police Department, it seemed, had won. Before Brandenburg announced that she would not run for re-election, two Democratic challengers, a former federal prosecutor and a former cop, entered the race to topple the flailing and vulnerable incumbent. “Democratic Party elites said, 'Just get out of the way and maybe this whole question about the DA’s office and the police will go away,'” said Correia. “The police shooting issue is not a big part of the current race.” Instead, the candidates declared their intention to rebuild the partnership between the DA's office and the APD.

And so the longest-serving district attorney in Bernalillo County history will exit in the shadow of her failures. Since the charges in the Boyd case, Brandenburg has not prosecuted any other officers for shootings. She and her staff have 30 open police shooting cases pending review. The files sit in cardboard boxes on a steel shelf in her office. “This is a priority of our office,” Brandenburg said at a press conference. But it is not. None of the attorneys in her office are specifically assigned to handle the cases. Instead, her attorneys review the police shooting cases only when they have time to spare. “We do that in addition to our day job,” she said. “That’s just what we do on weekends and nights.”

Nobody on staff seemed to want this extra work. The backlog of police shooting cases had become an inside joke around the office. Brandenburg sat at the front of the conference room at a morning staff meeting, her managing attorneys gathered around her, and she tried to keep a straight face. She pointed to a fresh-faced young attorney named Devin. Devin, she told the room, had recently done a great job writing a letter for her. She was impressed by his writing ability and knew how to put it to good use. “Devin’s gonna start doing officer-involved shooting reports,” she said dryly. The room erupted into laughter. They all knew she was kidding. •