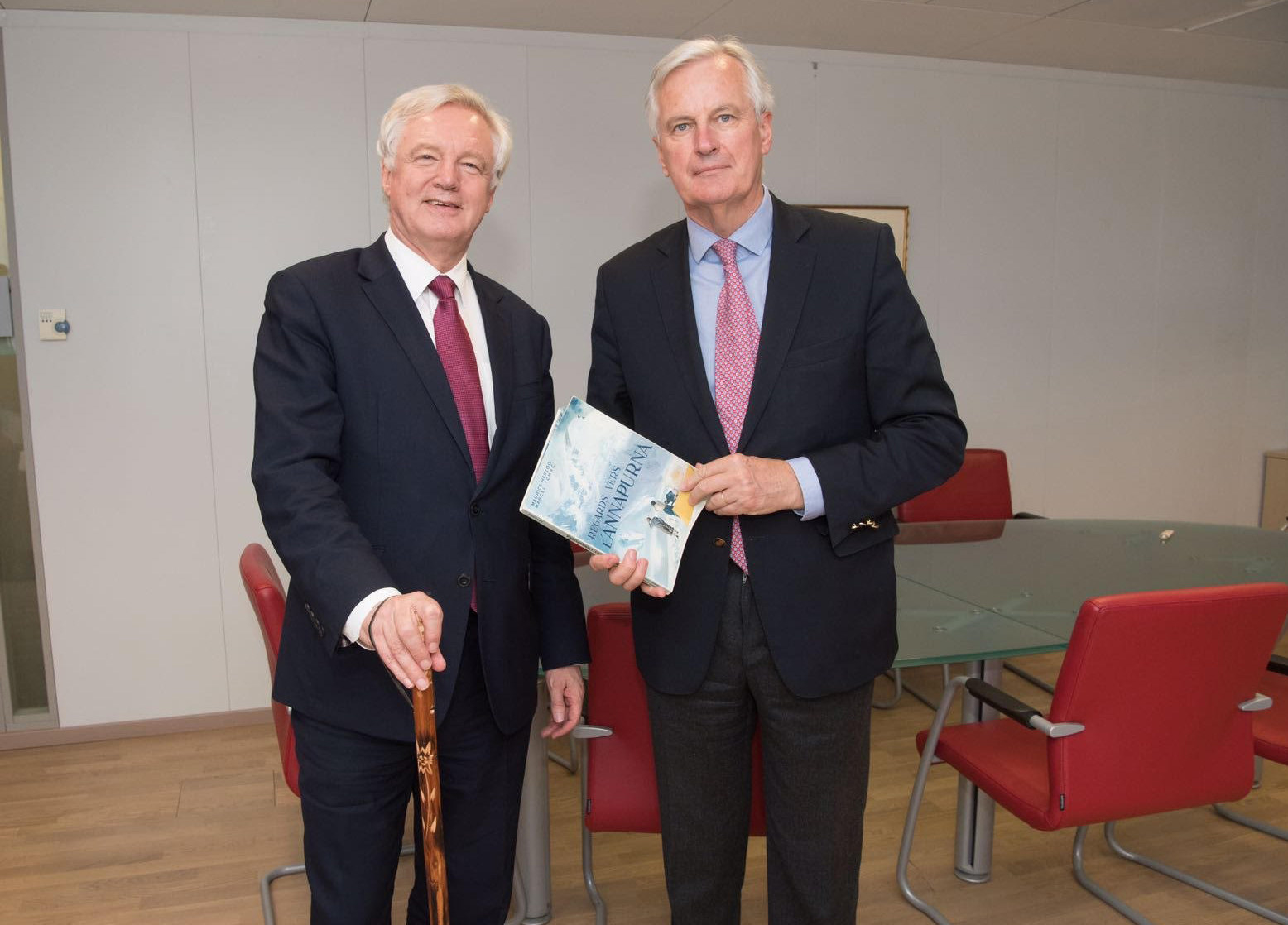

David Davis is the UK Brexit secretary, the head of the Department for Exiting the European Union, and Britain's lead in negotiations with the EU.

However, it is the prime minister, Theresa May, who is getting the lion's share of the praise from Tory MPs after the European Commission said that “sufficient progress” had been made to move on to the second phase of Brexit talks – and the remaining 27 member states (the EU27) are now expected to sign off on the deal.

This was the same week that Davis stunned Westminster by revealing the government hadn't carried out any impact assessments on leaving the EU, the latest in a series of apparent inconsistencies and off-the-mark predictions since he became Brexit secretary.

This is how the negotiations have gone versus how the Brexit secretary thought they would play out:

The timetable

Davis predicted in May that agreeing a timetable for the negotiations would be the “row of the summer”.

.@DavidDavisMP explains why we're heading for a row with the EU over Brexit this summer #Peston

But a few weeks later, and with summer still days away, the Brexit secretary agreed to the sequenced approach set out by the EU’s negotiating stance on the opening day of talks.

The divorce bill

For months the UK government was adamant it would not agree to a £50 billion so-called Brexit divorce bill – and denied any reports that suggested otherwise.

In September, the Brexit secretary called the figure “rubbish”, “nonsense”, and “completely wrong”.

This was @DavidDavisMP on @MarrShow 3 September telling the public a £50bn Brexit divorce bill is "rubbish, nonsens… https://t.co/yIJKwR6VB7

Although Friday's agreement contained no figures, Downing Street has confirmed that it expects the bill to be between £35 billion and £39 billion, while the Financial Times reported the EU put the figure at around €55 billion (£48 billion).

However, the final bill calculations may vary depending on, for example, whether items such as contingent liabilities, loans to Ukraine, and development funds are included.

The single market and customs union

The Brexit secretary has on a number of occasions suggested that the UK would leave the single market and customs union in 2019, and that freedom of movement would at that point also come to an end.

Speaking at the Times CEO Summit in June, Davis explained to business leaders the UK will have left the EU single market and customs union by March 2019, and said that securing a trade deal with the EU within two years would be "simple". He also claimed the UK would strike independent trade deals immediately after Brexit in 2019. And asked if Britain would pull straight out of the customs union, he said: "I would have thought so."

In March Davis said this to the Brexit select committee about transitional arrangements:

When I was here last, we talked about this at very great length and I made the point that we needed to distinguish between the range of views of what a transition arrangement means, which is why we used “implementation period” as a better phrase. The range of views, just to remind you, range from the views taken by some members of the [European] Commission that we will do the “divorce”, the departure deal, and then after that have a transitional arrangement while we are still paying money and there is still the free movement of people. There are all of these things going on and we will do the long‑term deal in slow motion. That is plainly not what we are after. That is the first thing to say.

Guidelines the EU27 are set to adopt next week will spell out that the UK would remain in the customs union and single market (with all four freedoms, including of movement of people) during the transition period. Britain would have to accept the full body of EU law and responsibilities during the two-year period, but would lose its seat at the table and its place in EU institutions:

In order to ensure a level playing field based on the same rules applying throughout the single market, changes to the acquis adopted by EU institutions and bodies will have to apply both in the United Kingdom and the EU. All existing Union regulatory, budgetary, supervisory, judiciary and enforcement instruments and structures will also apply.

Such an arrangement would also mean the UK will not be able to conclude trade deals right after it leaves the EU in 2019.

European Court of Justice

Back in May, Davis made a feisty argument against any role for the European Court of Justice (ECJ, or CJEU) in the UK after Brexit, telling ITV: "The simple truth is we’re leaving. We're going to be outside the reach of the European Court, we're going to be outside the reach of all of the law-making capabilities of the EU.

"There are many ways of guaranteeing this [rights for EU citizens]. We don't see a need to give in to the European ideology on the ECJ – we've got very good courts."

The truth turns out to not be so simple. Today’s agreement states that the ECJ will play a role in guaranteeing and protecting citizens’ rights for eight years after Brexit:

In the context of the application or interpretation of those rights, UK courts shall therefore have due regard to relevant decisions of the CJEU after the specified date. The Agreement should also establish a mechanism enabling UK courts or tribunals to decide, having had due regard to whether relevant case-law exists, to ask the CJEU questions of interpretation of those rights where they consider that a CJEU ruling on the question is necessary for the UK court or tribunal to be able to give judgment in a case before it. This mechanism should be available for UK courts or tribunals for litigation brought within 8 years from the date of application of the citizens' rights Part.

Meanwhile, the terms of transition set out by the EU27 will mean the UK will have to continue to abide by Europe's laws, rules, and courts during the interim phase.

Negotiating a trade deal during the transition

Finally, looking ahead, Davis has said he does not “envision” the UK continuing to negotiate a trade agreement during the transition.

However, the guidelines the EU27 are set to adopt next week will make clear that “an agreement on a future relationship can only be finalised and concluded once the United Kingdom has become a third country [after March 2019]”. Before then the EU will engage only in “preliminary and preparatory discussions with the aim of identifying an overall understanding of the framework for the future relationship”, and “such an understanding, which will require additional European Council guidelines, should be elaborated in a political declaration accompanying the Withdrawal Agreement”.

Most experts, including the UK’s former ambassador to the EU, believe there simply isn’t enough time to conclude a trade deal before Brexit, while the government itself has effectively conceded the exit deal will not be conditional on a trade deal.