"I guess a lot of people think I’m a classic career politician," says Joel Mason. "You know the sort of thing – contest a no-hope seat, come back in a few years’ time and have a go at one where there’s a real chance.

"But the thing is, I’m a Lib Dem. A safe seat… I mean… It’s not really a thing."

The city of Exeter is a Labour stronghold. Mason is going to spend most of this afternoon knocking on the doors of people who either don’t care about politics, or are long-term Labour voters and so will be even less interested in what the 22-year-old has to say. It’s bitterly cold, and there’s a vile, strong drizzle that soaks you in seconds. A waterproof would make it tolerable, but I didn’t pack one. I did take on board a couple of whiskeys before setting out, but as it turns out, they don’t really help.

Who is Joel Mason? And why did I want to go out canvassing with him? Six months ago, he was a normal student at Exeter University: a tall, rugby-playing young man from Bedfordshire who looks even younger than his age. He tells me he’d "always been interested in current affairs – non-partisan politics, if you will".

He asked people to vote Lib Dem in 2010, but couldn’t vote himself as he was only 17. At university, he joined the Lib Dem society. But he was still planning on focusing on his exams and getting a degree: "It would’ve been the sensible thing."

But one night in the pub, "I was saying it was annoying how the Lib Dems don’t get a fair hearing – we should be proud of what we’ve done in government, we’ve done the right thing, and we need to get our message out there more. ... Someone told me the local party hadn’t chosen their candidate … so I thought, Why not throw my hat in the ring?"

By the beginning of February, he was the Lib Dem candidate for Exeter. In the early hours of 8 May, he’ll find out if he is the city's new MP. A few hours later, at 9am, he’ll sit his final exams.

What does it say that one of our main political parties is putting up an undergraduate to contest a major city? Is it an indictment of British politics? Have the Lib Dems just given up on the grounds that they don't have a hope of winning the seat?

Mason can't expect to win. When I ask him why he's running, he says he wants to give people the "democratic choice" to vote for his party, and because "there are lots of things we can be incredibly proud of", so he wants the public to give his party a "fair hearing".

At 2pm, the local Lib Dem battlebus – a tiny, battered silver car with some flags attached to the windows – rolls up. The car belongs to Adrian Fullam, the leader of the Liberal Democrat council in Exeter.

Also joining us for the afternoon are some students from the university’s Liberal Democrat society. They see my photographer and worry about how their all-male team looks. One had wanted to bring his girlfriend, but she’s dropped out. I can't say I blame her. The rain’s now stinging my eyes, and I think my fingers are about to drop off.

"It’s hard," says Fullam. "Bradshaw [Ben Bradshaw, the city’s Labour MP] can employ staff members – but I’m in a full-time job and Joel’s at university."

Bradshaw looms over every political conversation you have in Exeter. He’s been the city’s MP for nearly 20 years. He took the city in 1997 with a massive swing – and while the Tories have closed the gap a little, it would be a huge surprise if he lost his seat this time round. His posters are everywhere.

"I think he’s a really nice bloke," says Mason. "He gives me lots of tips after hustings, probably because he doesn’t see me as a threat. But I feel one of his skills is making left-wing people believe he’s completely on their side, even though he’s an arch-Blairite. On NHS outsourcing, for example, I’ll say what I think: I have no objection to it in principle if contracts are drawn up properly. But Bradshaw will say something like, 'Yes, it’s hugely concerning,' and you don’t notice that he’s actually said pretty much the same thing as me."

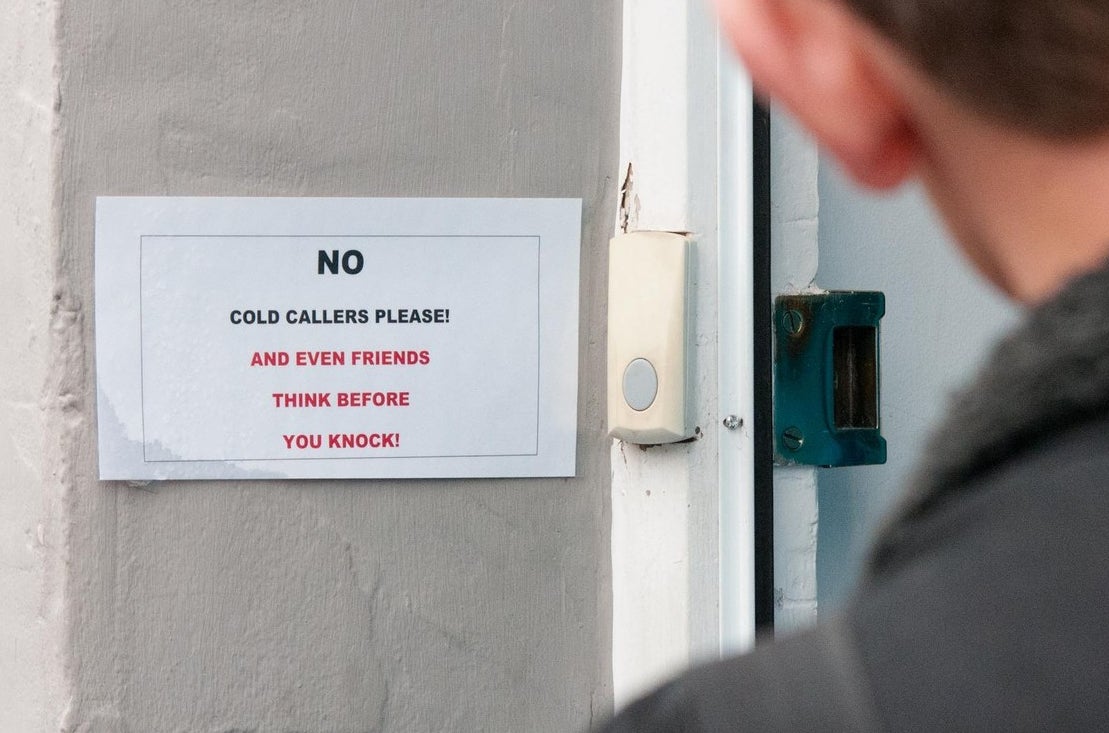

The team begin knocking on doors. The ward of St Thomas, just to the west of the River Exe, overlooked by the verdant hills of the Exwick valley, is a pleasant residential area in which about 6,000 people live, mostly in Victorian terraced houses. It seems most of them either aren’t in or don’t answer the door.

One house is festooned with Bradshaw posters. "I’m guessing you won’t be bothering with that one?" I ask Fullam. "Oh, he hates me. We could knock if you like. Might be fun." He seems to know most of the people who live here.

The canvassing operation isn't just about trying to pick up some votes for Mason. It's also a data-gathering exercise. Mason and his team relay voting intentions to Fullam – "voting Labour", "undecided" – and he puts them into an app on his phone that keeps a record of their historical voting patterns. It’ll allow the party to keep a track of how they’re doing, and chase up people on polling day who might vote for them, among other things.

The other reason they’re doing this is to remind people that there are local elections taking place too, and to get them thinking about them. Fullam’s election leaflet actually spells this out in capitals; in fact, pretty much all it says is that this is both a NATIONAL and a LOCAL election.

Mason knocks on a door. A man answers.

"I don’t really have a problem with the Lib Dems – I think Vince Cable’s a good bloke," he says. "But I do have a problem with Lib Dems together with the Tories."

Mason and Fullam hear this a lot. The man reels off a list of reasons – above all, he’s a civil servant, and he's seen scores of job cuts at his place of work.

"Fair enough," says Fullam. "But how will you be voting locally?"

In 2012, Labour gained control of the city’s council for the first time since 2004. It has 27 of the city's 40 councillors. There are only three Lib Dems. The party's activists worry Exeter will turn into a one-party city – that democracy will begin and end with Labour’s selection panels, and it'll be too much of a mountain to climb for other parties to even bother competing. One of the team cites the recent scandals in Rotherham as an example of the kind of thing that can go wrong when a ruling party isn't held to account by an effective opposition.

Fullam, an avuncular, middle-aged man with greying hair and a pretty broad Devonian accent, has been a local councillor for years – but now he’s got a fight on his hands. As Mason tells me: "We’ve lost a lot of councillors, a lot of good people who actually care about the local areas – they got kicked out due to disillusion with the national party."

And this is really the story at most of the houses we visit. No one really seems to take issue with the Liberal Democrats or their policies, but they certainly do with the coalition. It's not that people aren't happy to talk to the activists – on the whole, those who answer the door are generally happy to give them a fair hearing – but everything comes back to the coalition.

Perhaps the most enthusiastic response Mason and his team get is from a couple of small children who seem entranced by his yellow clipboard.

Government's been an unmitigated disaster for you, hasn't it, I say to Mason. "I maintain it was the responsible thing to do to go into coalition," he replies. "It would've been fundamentally wrong for Nick Clegg to put the party’s interests above the country."

Mason is happy to defend his party’s record in government: "We’ve got one-sixth of the coalition’s MPs. Naturally we’ll have less influence than the Conservatives." He reels off a list of achievements that he says haven’t "cut through" because the party was "less canny" than Labour or the Tories in promoting them. "If you cast your mind back to 2010, Nick Clegg turned to David Cameron [in the TV debates], he said, 'Will you lift the [income tax] threshold?', and Cameron said there wasn’t enough money. … Here in Exeter, 6,000 of the lowest earners don’t pay any tax at all. We can say, 'That’s the Lib Dems in government.'"

Likewise, he says, "More Tory MPs voted against gay marriage than for. I’m not denying David Cameron supports it – it’s indicative of the degree to which he’s at odds with his party." And there's also the pupil premium: "In Exeter there’s been over £8 million of additional funding targeted at the most disadvantaged pupils."

But then look at all the policies Liberal Democrats failed to stop. What about the bedroom tax and assorted welfare cuts – are they Lib Dem policies? "It’s difficult because we’re dealing with counterfactualism," Mason replies. "I don’t know what went on behind closed doors. But if you look at what the parties would do [after the upcoming general election] – £12 billion of welfare cuts is indicative of the sort of thing [the Tories] would have wanted to do if it hadn’t been for us."

He repeats some of these arguments with people on the doorstep. It’s hard to say how many voters he picks up as a result. To be honest, it seems unlikely he’ll win over many.

Partly, this was always something of a hopeless venture. Most voters have made their minds up by now. Some party activists will even tell you that leafleting is rather more effective than talking. Leaflets serve as a way to remind a mass block of voters that your party is active in the local area, and that’s more valuable than sporadic chats on the doorstep, however well targeted they may be.

A little later we drive up a hill overlooking the city. Mason has been approached by a potential voter on Facebook who said she wanted to talk to him. "I have no idea what she wants," he says. "She probably wants to shout at me." You get the sense he’s getting used to this.

We walk into her house with some trepidation. In fact, the woman – Kerry Pankhurst, 35, a young mother who works at the city's university – just wants to speak to him because she’s unsure about how to vote. She grills him extensively and he answers eloquently and thoughtfully. It’s the sort of setting within which Mason is more comfortable: By his own admission, his least favourite thing is trying to convey his thoughts in a snappy soundbite.

One of the things she’s most keen to ask him about, of course, is tuition fees. It's one of the first things I asked him about today too. Why on earth would a student ever support the Lib Dems given how the party betrayed them?

"In 2010 we had that policy [of abolishing tuition fees] because we didn’t want people’s socioeconomic background to become an impediment to going to university," he told me then. "We had this policy which was a good headline and quite a badly targeted policy, and what we’ve got now is a policy which takes that same sentiment of everybody being able to go to university and no one’s background being an impediment – so we’ve got quite a good policy but a pretty awful headline.

"Under the new scheme if you benefit hugely from your degree then you pay more. I think that’s fair enough. That money goes to subsidising access for the most disadvantaged. … It’s a progressive policy."

He also claims that there is now more help available for more disadvantaged students than there had been under Labour: "And that’s partly why applications from students from disadvantaged backgrounds are up compared to before."

Labour's recent pledge to cut tuition fees angers him. "One of the problems in politics is that there’s always this tendency to go for a snappy soundbite," he told me. "Vince Cable said the other day, Labour just couldn’t resist it, and that’s why they introduced what sounds like a progressive policy, reducing fees – but it’s bullshit. The only people who benefit from that are people on the highest incomes, those graduates who end up earning huge amounts of money. They won’t pay back so much, and it’s no help at all."

But if the policy’s so great, why did Nick Clegg apologise for it? "He apologised because it was a broken promise … but I think Clegg would be the first to say exactly what I’ve said. I think there are a lot of benefits from the new system … The people paying more are the people who get £50,000 jobs in the City, and frankly I say fine, why not have them pay back more, because they can afford to?"

He added, apologetically: "Most people can see the benefits of the system … but I took five minutes to explain that to you. That’s one of the challenges."

He takes about four minutes to make the argument to Pankhurst, which suggests he’s learning on the job. Pankhurst, it turns out, is quite the doughty interviewer. She wants to know how the Lib Dems will meet their funding pledges. About childcare costs, the defence budget, the NHS, immigration, the bank levy, and so on.

However patronising it might sound, Mason speaks incredibly well for a 22-year-old. He's particularly thoughtful on mental health. "We’ve managed to secure £1.25 billion under this parliament," he told me earlier. "I think it’s a scandal it’s been neglected, historically. ... Whoever’s in government, I hope they address this issue. Far more men commit suicide than women but far few men come forward with problems, and I think that’s because there’s a societal stigma."

In the end, Pankhurst tells Mason that in spite of his years, she’s impressed. "Maybe we need some new blood," she says.

There’s something hugely reassuring about this scene. There’s an honesty about this connection between voter and politician that one rarely sees: a reassurance that at least one voter won't decide until she's heard a politician's words and looked into their eyes. Mason slips up at one point on the subject of pensions, and Pankhurst corrects him. "You know what I mean though," he says. She smiles: "I do."

If I'm totally honest, I probably wanted to go canvassing with him because I thought it might be a car crash. But I like Mason, and what he stands for – not his party per se, but his earnest belief in the policies he’s attempting to sell. You might find it misguided or naive, but he is hugely proud to be a member of the Lib Dems and shows a great deal more passion for their policies than any number of more famous candidates.

I’m also aware I’ve caught him at the proverbial strange time in his life. Assuming he doesn't win, he has no idea what the future holds for him. "I'll probably go and work for my dad for a bit – he's a dry stone waller." This could be his first and last stab at being a politician.

Still, at least he’ll have an appearance in Heat magazine’s “Hot Politician Special” to show for it.

At one point I ask him, and I feel like an absolute shit for doing so, "You realise you have absolutely no chance of winning, don’t you?"

He chuckles. "Well, I’ll be doing damned well if I do."